Perfect Timing, One Pot at a Time / Creating a Database of Pulse Cooking Times

USDA Plant Geneticist Karen Cichy leads an innovative project aimed at helping others in the field develop pulses that cook faster and are more convenient

Pulses may be many things in the eyes of the average consumer—nutritious, versatile, filling—but there is one adjective that isn’t normally used to describe dry legumes: fast. Though most of the cooking time needed to prepare, say, a pot of dry beans is passive, the fact that they take longer to become tender than pasta, rice or other staples may be the very reason so many pulses remain uneaten in pantries or unpurchased on store shelves. Add to this the recommended pre-soaking time of many pulses, and it is no wonder they aren’t necessarily considered a convenient, go-to meal for many consumers.

These perceptions do vary, of course, by region and culture. People’s preferences when it comes to cooking methods, the types of pulses they consume and how often they consume them are as diverse as their diets themselves. There are countries (India or Brazil, for example) where pulses are so essential as staple foods that the government must regulate their trade to ensure supply; in other places, pulses aren’t often consumed by most people, reserved—at least conceptually—for vegetarians or certain occasions (Argentina is a good example). Many practices when it comes to cooking and consuming pulses go back thousands of years and are unlikely to change any time soon. But new habits always seem to emerge, whether due to developments in nutrition or in the technology used to process and present foods in novel ways (the proliferation of pulse-derived flours in snack foods can tell us a lot in this regard).

Karen Cichy, a plant geneticist for the USDA, believes understanding these cross-cultural differences can help us find ways to transcend them in order to increase the consumption of pulses. She and her team have developed a citizen science project based on a survey that asks participants about how they prepare pulses and how long it takes them to do so. Having a public database like this, the first of its kind, would be invaluable to scientists working to develop fast-cooking varieties aimed at consumers who might shy away from pulses simply because of their perceived lack of convenience.

“Up until this point in our research to understand the genetic diversity of cooking time in beans and to breed faster-cooking bean varieties we cooked all the bean samples in our own lab,” Cichy explains. “Also the beans that we evaluated for cooking time were grown mostly in research fields. Our research results show that there is a lot of genetic variability for cooking time and some varieties cook faster than others when grown under the exact same conditions and held under the same storage conditions and cooked with the same method.”

“These findings indicated that we can breed beans that are faster-cooking—and we are doing that. But we are still missing information on how long beans—and all pulses—take to cook when cooked at home by consumers under their conditions. That is important because as we develop faster cooking varieties, it is helpful to have baseline data to set our targets.”

The survey itself is straightforward and based on the actual practice of participants: choose a popular pulse type (chickpeas, dry beans, dry peas, lentils or other); indicate the cooking method used (open fire, pressure cooker, slow cooker, stove top or other); indicate the fuel source (charcoal, electric stove, firewood, gas or other); say whether you soaked the pulses prior to cooking; record the amount of time it took you to cook them; choose your location; and finally indicate how often you eat pulses (everyday, 2 to 6 times a week, once a week or less than once a week). Participants can also add comments to indicate the name of the dish they prepared or what other ingredients were added.

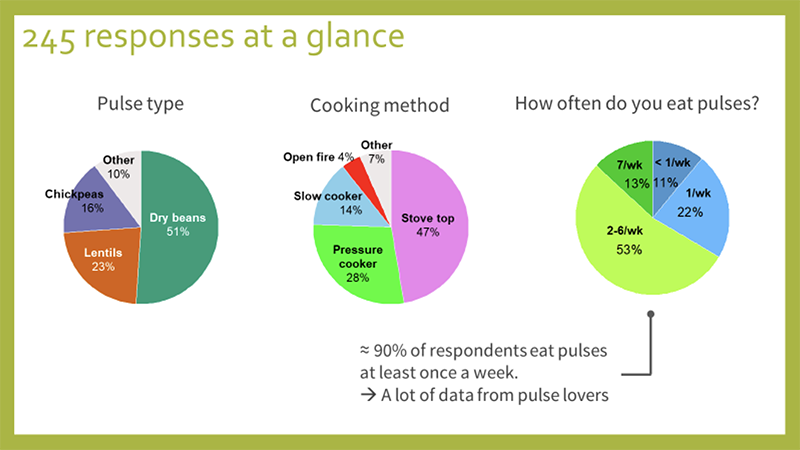

As of June 12 of this year, 245 people hailing from 27 different countries, including Australia, Uganda, Brazil, India, Türkiye and Mexico, had participated in the study. The United States was the most represented country (185 participants) followed by Canada (23), with the highest number of participants recorded in California and Michigan (the latter happens to be the nation’s top producer of black and cranberry beans).

Most participants (51%) chose to cook dry beans, followed by lentils, chickpeas and other beans. Black beans were the dry bean most often indicated, followed closely by pinto beans, with fewer respondents indicating other types of dry beans such as dark red kidney, speckled, navy, great northern, etc. Though she wasn’t surprised by this last data point, Cichy pointed out that the preference for black beans in the U.S. was not always the case.

“There has been an increase in black bean consumption and a decrease in navy bean consumption in the U.S., an indication that consumer preferences change over time and consumers are open to try new pulses and adopt them into their diets,” Cichy said. “The same can be said for the increase in garbanzo bean consumption in the US.”

Among those who cooked lentils, split reds were the most common variety, followed by brown, green, and whole red lentils. Not surprisingly, when it came to chickpeas, the desi variety came out on top, preferred by substantially more participants than the Kabuli variety. Other pulses that people prepared included dry peas, cowpeas, pigeon peas and mung beans, all of which will likely be represented to a greater extent as data comes in from the different parts of the world where these pulses are popular.

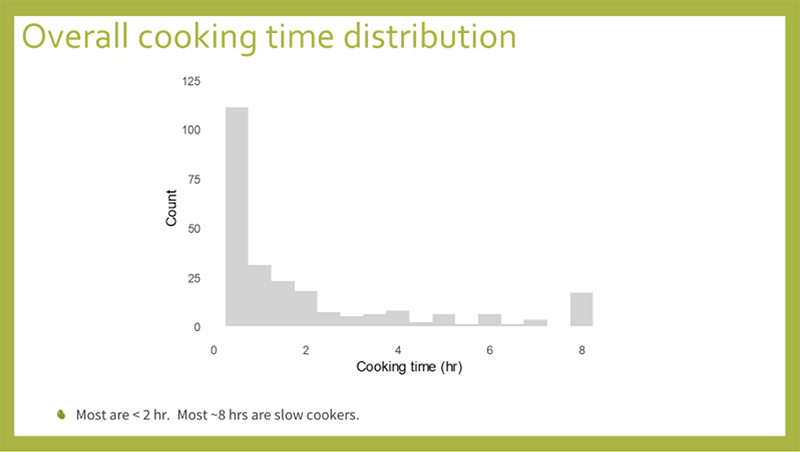

The survey results also revealed a certain degree of variety in terms of cooking methods. Stove top cooking was the most popular, with 47% respondents saying this was how they cooked their pulses, though 28% said they used a pressure cooker to accelerate prep time, which was reduced to an average 35 minutes as opposed to 1 hour for stove top and 2 hours for open fire.

“Using the pressure cooker is the most efficient way to cook dried beans,” said one person from Tulsa, Oklahoma who answered the survey. “Making black beans would take about 9-10 hours in the crock pot or at least 4 hours over electric stove top.”

“I have a pressure cooker now and have been able to cook every kind of bean from dry with no soaking,” another participant from Baroda, Michigan said.

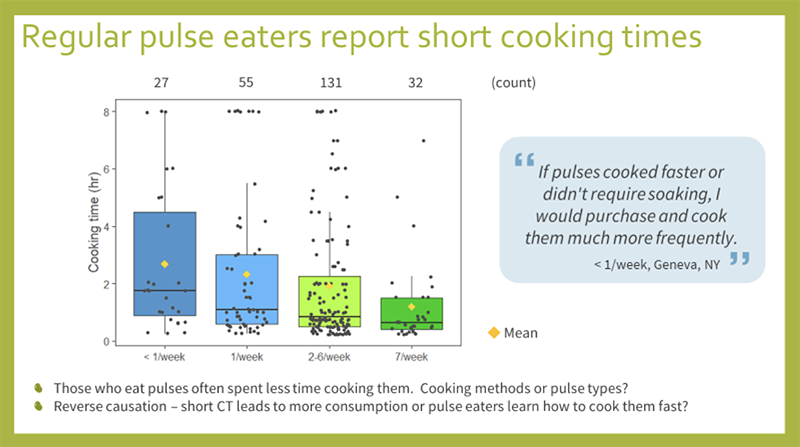

One clear indication when it came to cooking time is that, while dry bean cooking times vary greatly by cooking method and soak time, lentils cook faster than other pulses and are generally ready to eat in one hour or less, according to participants in the survey. Stove top cooking was by far the most popular method for lentils, whereas dry beans were prepared in a wider variety of ways. People also soaked lentils for much less time than dry beans, if at all. Most said they didn’t even bother to soak, as opposed to about 2/3 of those who cooked dry beans saying they soaked them previously. The most common response for soaking dry beans and chickpeas was 7-12 hours. These data points to a correlation between how convenient a certain pulse is perceived and how often people eat it.

“Pulse consumption frequency was negatively associated with cooking times,” wrote Rie Sadohara, a researcher in the Department of Plant, Soil, and Microbial Sciences at Michigan State University working alongside Cichy.

“This might be because of a difference in cooking methods and pulse types reported by each group, i.e. short cooking times may be due to lentils or pressure cookers. There is also a question of reverse causation. Does short cooking time lead to more consumption or does regular consumption lead to learning how to cook pulses fast? Either way, the association indicates the importance of cooking time for pulse consumption.”

The project thus reveals an interesting trend, that those who eat pulses regularly are more likely to know how to prepare them quickly. Whether this means those same consumers are more often choosing to prepare fast-cooking pulses (lentils), have figured out the ideal soaking-to-cooking ratio, have invested in a pressure cooker or some combination of these still remains to be seen, but these trends should become clearer as more data comes in.

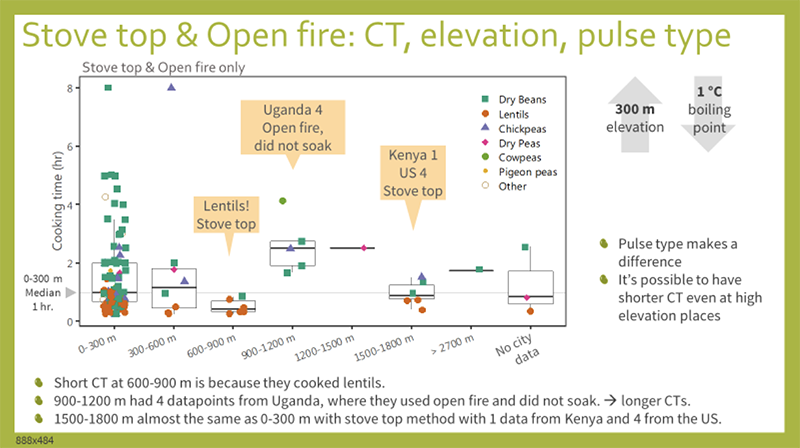

Comparing the results to the regions respondents were from also revealed some interesting findings. For one thing, cooking method varied greatly depending on where people were from: while many respondents in North America said they used pressure cookers, those from Uganda mostly cooked pulses in a traditional way using open fire and did not pre-soak, resulting in longer cooking times. Elevation also played a role: the higher the altitude, the lower the boiling point of water. Specifically, for every increase of 300 meters above sea level the boiling point drops by 1 degree Celsius. It will be interesting to analyze the relationships between these findings as more data is collected.

Cichy and Sadohara expect the project to have real implications in the laboratory, where they and their colleagues around the world can use the data to develop new varieties of pulses that cook faster, require less cooking time or are improved in other ways.

“This data will be used to gain baseline knowledge of how long pulses take to cook when cooked at home by consumers by different methods and to help identify targets for breeding. These methods can also be useful to understand other aspects that may influence cooking time such as how long and how pulses are stored prior to cooking,” Cichy said.

Rolling out these kinds of products, however, does present a unique set of challenges. Not only do consumers need to be convinced to try them and incorporate them into regular use; the farmers who grow them also need to be on board.

“I think farmers will be willing to grow new varieties if there is a market for them,” Cichy said. “One challenge would be if the fast cooking varieties have poor agronomic qualities or are more susceptible to pests or diseases then the varieties they are currently growing. Another challenge is establishing the value chain; for example, is there an elevator nearby that can receive a new pulse type and perhaps keep it separate from other classes/varieties.”

The Pulses Cooking Times: Citizen Science survey will be open until World Food Day on October 16, 2020. Once the data is analyzed, the findings will be published at pulses.org and potentially peer reviewed journal such as Nature Foods or Legume Science. You can participate in the survey here:

Pulses Cooking Times: Citizen Science

Disclaimer: The opinions or views expressed in this publication are those of the authors or quoted persons. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Global Pulse Confederation or its members.