December 14, 2020

The two category 4 hurricanes hit the region in November just as bean crops were nearing harvest.

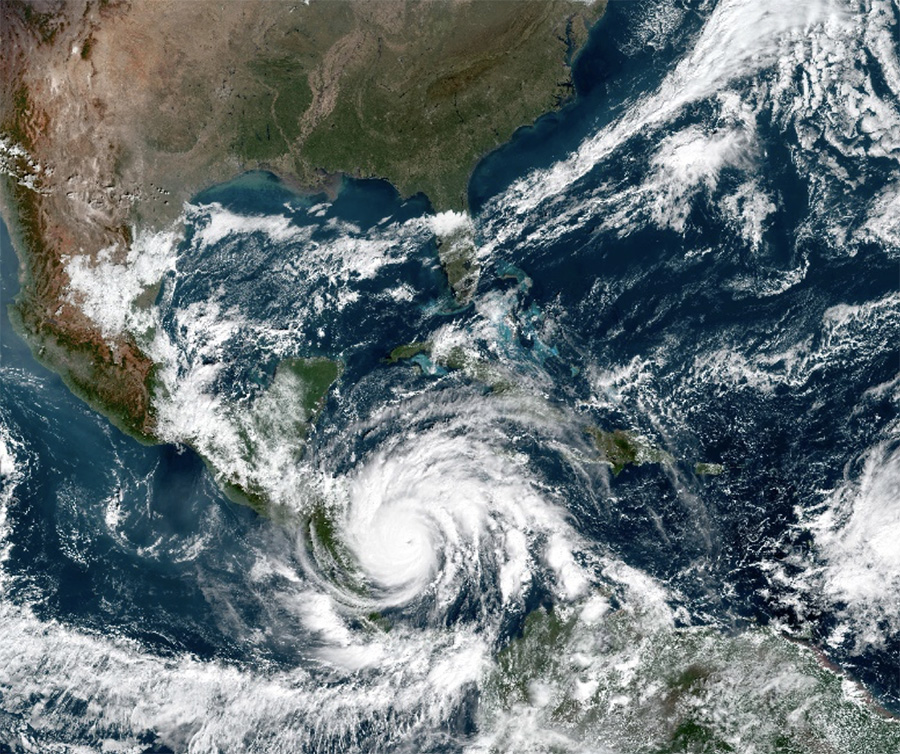

Hurricane Iota. Photo from NASA Visible Earth.

Two category 4 hurricanes struck Central America within a two-week period in the month of November. The first, Eta, made landfall on November 3 near Puerto Cabezas in northeastern Nicaragua. Over the three days that followed, it continued on across Honduras and Guatemala as a tropical storm, dumping large amounts of rain and causing flooding and mudslides as it went.

Just thirteen days later, with the region still reeling from the destruction left in Eta’s wake, a second hurricane, Iota, hit Nicaragua again, this time near the town of Haulover. Iota, the strongest hurricane recorded in 2020, made landfall on November 16 and affected much of the same area as Eta, causing additional flooding, mudslides and catastrophic destruction.

As of November 28, Relief Web, the information service of the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, reports the combined death toll from the two hurricanes at 189 with an estimated 5.2 million people in the region affected by the devastation. Damage to bridges, roads and other infrastructure is estimated in the millions of dollars. All of the countries on the Central American isthmus were impacted to some degree or another, with Nicaragua and Honduras the hardest hit.

At the time of the storms, several Central American countries were about to harvest bean crops and/or preparing to seed crops. The region produces mainly red and black beans. Alejandro Leloir, the U.S. Dry Bean Council’s Regional Representative, says that initial reports indicate 30-40% of the bean crops across the region were affected.

“This could mean there will be more import demand from the region,” he says.

To get a fuller picture of the situation on the ground, the GPC checked-in with sources in several Central American countries.

Nicaragua mainly produces the rojo seda bean type, a red bean that is indigenous to the isthmus and preferred by Central American consumers. Nicaragua is the region’s primary supplier of rojo seda beans, usually producing more than enough to meet its own domestic demand and to cover any shortfall in other Central American countries. It routinely supplies red beans to Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras. The country also produces a smaller black bean crop (less than 2% of annual production).

As previously mentioned, both hurricanes made landfall in Nicaragua. The government reports the storms caused $742 million in losses, including damage to housing and infrastructure. Alvaro Vargas, president of the Unión de Productores Agropecuarios de Nicaragua (UPANIC), a grower’s group that represents the major ag sectors at the national level, reports that Eta alone destroyed 1,176 km of rural dirt roads and bridges across the country, severely disrupting the flow of agricultural goods to market. The dairy sector, says Vargas, was especially hard hit. Nicaraguan dairy farmers produce 1 million liters of milk a day and the crippled roadways made it a challenge to deliver such a large volume of milk to the processing plants.

In terms of dry beans, Vargas indicates the country typically seeds 335,000 manzanas (about 234,500 ha.) and produces 4.5 million cwt (about 228,600 MT) annually. Of that amount, 2.5 million cwt (113,300 MT) are consumed internally, and 2 million cwt (90,700 MT) is exported. The country has three dry bean crops a year: the Primera, Postrera and Apante.

The hurricanes hit just as the Postrera crop was nearing harvest. The growing areas most affected by the storms were in the departments of Jinotega, Matagalpa, Nueva Segovia and Estelí, says Vargas. The closer the crop was to maturity, the worse it fared, he explains. Vargas estimates the storms reduced Nicaragua’s Postrera dry bean crop by 50%.

As dramatic as this sounds, it should be noted that Nicaragua had previously harvested a good Primera dry bean crop. Primera bean production is estimated at 1.5-1.6 million quintals (about 68,000-72,600 MT), enough to cover domestic consumption.

“I don’t believe the nation’s food security is at risk,” says Vargas, “as long as we promote greater seeding this Apante season.”

The Apante bean crop is the largest of the three. Normally, the seeding of the crop starts in mid-December, but with the Postrera season losses, some growers are starting in early December. Because of the hurricanes, the crop is going in the ground with favorable soil moisture conditions.

It is vital, Vargas stresses, that everyone involved in Nicaragua’s pulse sector get behind efforts to expand the Apante bean area. Seeding more beans will not be easy, he says, given that Nicaragua’s agricultural production is in the hand of smallholder farmers. With the losses in the Postrera bean crop, they will have less seed for the Apante season. To make matters worse, farmers are now seeing higher production costs due to a 2019 tax law that, for the first time in Nicaragua’s history, requires growers to pay taxes on farming inputs and equipment. Given the country’s ongoing socio-economic crisis, these costs cannot be passed on to consumers, as they are already hard pressed to meet their basic needs.

UPANIC is doing its part. The group is launching a pilot program for smallholder farmers in the areas hardest hit by the hurricanes. The program seeks to expand the bean area by providing at least 100 growers with a tech kit that includes certified seed to plant one manzana (about 0.7 of a hectare) of beans, as well as some inputs and basic farming tools.

“We are also engaged in a campaign to get others involved to help us increase the bean area this Apante season,” says Vargas.

Looking beyond the Apante season to next year’s Primera season, UPANIC is exploring ways to have an even bigger impact in guaranteeing the country’s food security.

For now, though, the focus is on the seeding of the Apante crop.

“If we don’t act now to expand the area this Apante season, the supply-demand balance will be at risk,” Vargas warns.

Bean field in Estelí Department. Photo courtesy of UPANIC.

In Honduras, the rojo seda is the bean of choice, accounting for nearly all of the nation’s bean consumption. To meet internal demand, the country supplements its domestic production with imports. Its primary supplier is Nicaragua.

Relief Web reports that hurricane Eta was the worst natural calamity to hit Honduras in more than two decades. The storm impacted about 30% of the country’s population, driving tens of thousands of people into cramped shelters, placing them at an elevated risk of contracting COVID-19. Eta also caused extensive damage to infrastructure, leaving some vulnerable communities isolated. Initial reports indicate that more than 318,600 hectares of crops were either lost or damaged by the excess rainfall. When Iota hit, Eta’s waters had not yet fully receded. By the time the second storm had passed, 16 of the country’s 18 departments had been impacted.

At the Grupo Jaremar plant just outside San Pedro Sula, operations manager Silvio Molina says that Eta flooded the warehouse, with the water level rising up to 2 meters, spoiling much of what was stored there, including beans.

At the time the hurricanes hit, the Segundo dry bean crop was about a month away from harvest. The Segundo is the smaller of the country’s two dry bean crops. According to a news report, 22,455 manzanas (about 15,720 hectares) of beans were lost across 15 departments. Production losses are estimated at 359,280 quintals (about 16,300 MT), representing 12.9% of estimated national production of 2.8 million quintals (about 127,000 MT). In some parts of the country, such as in Olancho, bean crop losses were total, says Molina.

Despite the losses and damage caused by the storms, the Secretary for Economic Development Maria Antonia Rivera assured the press that prices of food staples like beans should remain stable.

Molina, though, sees it differently.

“Highways are wrecked,” he says, “which makes it difficult to deliver product to market. There are not many beans available and prices have shot up by 50%. Those who have beans want to sell them as if they were gold.”

Grupo Jaremar’s plant outside San Pedro Sula. Photo courtesy of Silvio Molina.

Belize is the second biggest dry bean exporter in Central America. Although it is located on the Central American isthmus, the country has closer trade ties with the Caribbean because of its history as a former British colony. Belize produces light red kidney beans and blackeye peas. Light red kidney beans are consumed domestically and exported. Blackeye peas, however, are produced exclusively for export.

Belize was spared a direct hit from the storms, but both dumped heavy rain on the southern and central parts of the country, causing severe flooding and cutting off roadways, leaving communities isolated. Eta alone dumped 10-25 inches of rain across the country.

In the Mennonite community of Spanish Lookout, where a good part of the country’s beans are grown, Lyell Banman, sales representative of the Bel-Car Export and Import Company, reports that the storms caused the Belize River to flood, blocking the main access to the community for weeks. During that time, an all-weather back road that the community built a few years back provided the only avenue to bring in supplies.

Spanish Lookout is located in western Belize, where the planting of the bean crop typically gets underway in late November. Banman expects seeding this year to progress normally in his area. But in northern Belize, where beans are usually planted earlier, the excessive rainfall from the hurricanes will delay seeding.

According to Banman, Belize’s bean inventories have been cleared out since October. Strong domestic demand is likely to take a good part of the 2021 light red kidney bean crop, and the blackeye pea crop is sure to see good demand from the Caribbean. Given the strong demand and attractive pricing, Banman anticipates production of 3,000 – 4,000 MT for each bean type in 2021.

He cautions, however, that: “There is a possibility that the seeding acreage will be affected by the hurricanes. If the soil does not dry quickly enough, planting will be hindered and possibly reduced.”

Flooded bridge on main roadway. Photo courtesy Bel-Car Export and Import Company.

On average, Costa Rica produces nearly 14,000 MT of black and red beans per crop year and consumes about 50,000 MT. To bridge the gap, the country’s dry bean sector imports red beans mainly from Nicaragua and black beans primarily from the U.S., Argentina and China.

Like Belize, Costa Rica was spared the brunt of the storms. Even so, heavy rains caused significant damage to infrastructure. The highway system alone suffered nearly $15 million in damages. More than 2,000 people were displaced, and two lives were lost. The impact on agriculture, however, was not as severe as that caused by hurricanes Otto and Nate three years ago.

Walter Elizondo Mora, an analyst with Costa Rica’s Consejo Nacional de Producción (National Production Council) reports that Costa Rica’s Segundo crop had already been planted at the time of the hurricanes. Typically, 8,000 – 10,000 hectares are seeded to beans in the Segundo season.

Elizondo indicates that in the southern growing areas, 5,000 hectares had been seeded (70% red beans and 30% black beans) and were in the pod-filling stage when the hurricanes hit. The excess moisture has given rise to disease concerns and is likely to deteriorate grain quality. Elizondo says preliminary estimates place bean crop losses at 25%.

In the northern growing regions, the seeding of the Segundo bean crop occurs later than in the south. In the aftermath of the hurricanes, there is concern that seeding may be delayed due to waterlogged fields. Black beans account for 50% of the northern bean crop.

Elizondo also points out that in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, the government of Costa Rica has increased its buying of domestic bean production, especially black beans, for public food distribution programs. This has driven up prices. Elizondo reports bean prices have increased 2-3% on average since the start of the pandemic.

Bean field in Costa Rica. Photo courtesy CNP.

Central America / Eta / Iota / Costa Rica / Honduras / Guatemala / Nicaragua / El Salvador / Postrera / Apante / Alvaro Vargas / Silvio Molina / Lyell Banman / Walter Elizondo Mora / National Production Council

Disclaimer: The opinions or views expressed in this publication are those of the authors or quoted persons. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Global Pulse Confederation or its members.