In just a few short years, pulses from the Black Sea Region have exploded onto the world stage, catching the attention of pulse importers and exporters alike. For the former, the region offered competitively priced product. For the latter, stiff competition.

To get a better understanding of the Black Sea region’s pulse sector, GPC turned to Sergey Feofilov, a familiar name to many industry members. Born in Moscow, Sergey holds a PhD in Economics from Kiev National University. He got his start in agriculture as a grain and agricultural equipment trader. Then, during the ’90s, he worked for a state-owned company in the Ukraine, providing analysis on the trade of agricultural commodities. Sensing the tremendous potential of the ag sector in one of the world’s biggest grain producing and exporting nations, Sergey soon launched his own consulting company, UkrAgroConsult.

“After the collapse of the centrally planned economy, commodity traders looked for reliable and independent sources of information and analysis,” Sergey explains. “UkrAgroConsult was created to fill the vacuum, providing up-to-date market reports and research.”

Founded in 1994 and based in Kiev, the company has 25 years’ worth of expertise in Black Sea agricultural markets, delivering quality market information and analysis to agribusiness clients in more than 50 countries.

Pulses became part of UkrAgoConsult’s portfolio on the advice of friends and business contacts, who tipped Sergey off to the important role the Black Sea region could play in the growth of world pulse markets. Quickly seizing the opportunity, Sergey made UkrAgroConsult one of the founding partners of the Ukraine Pulse Association.

At the GPC’s request, and with the countries of the Black Sea region about to harvest their 2019 pulse crops, Sergey provided us with his insights into the region’s pulse sector.

Dry Peas from Russia and Ukraine

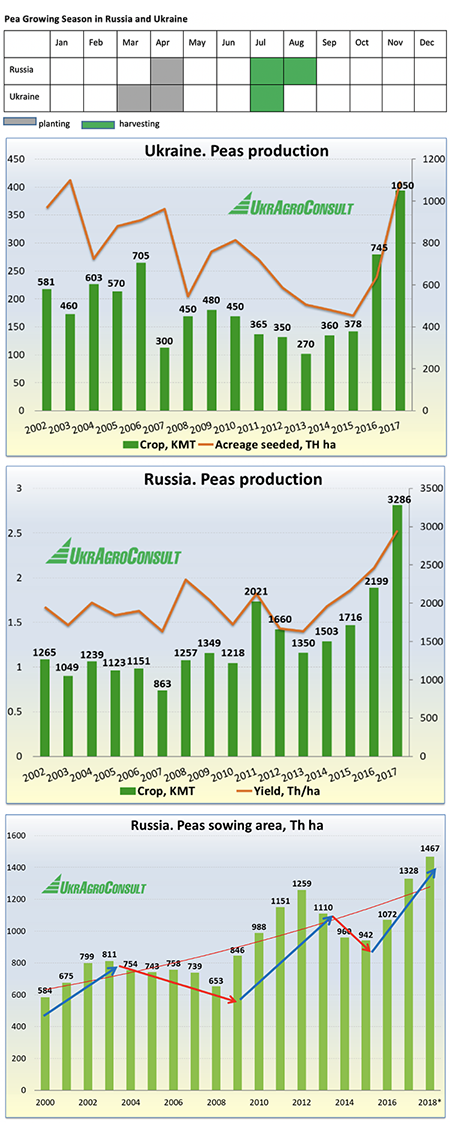

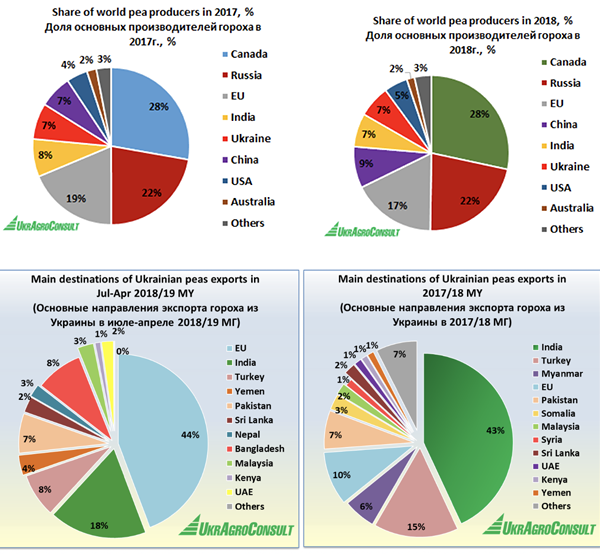

Dry peas are the major pulse crop grown in Russia and Ukraine, accounting for 75-80% of annual pulse production in those countries. In 2017, both countries harvested a bumper pea crop, which enabled them to expand their participation in export markets.

Encouraged by the success of the 2017/18 campaign, growers in the Black Sea region planted even more pulses in 2018. In Russia, for instance, pulse crops were planted on a record 2.78 million hectares. Peas accounted for 53% of that total (1,467,000 ha.), a record in and of itself and an 11% increase over the year before.

Despite the record area, however, Russia’s pea production was down in 2018 due to short moisture levels in the southern part of the country, a key pea growing area. In the Central and Volga federal districts, yields dropped 20% to 1.24 MT/ha. This marked the first time since 2013 that Russia’s year-on-year pea production experienced a decline. Looking at Russia’s overall pulse output, production was down from the previous year’s record 4.26 million MT to 3.43 million MT in 2018, a 19% decrease.

Even with a smaller crop, though, Russia maintained its position as the world’s second biggest pea producer.

As to be expected, Russia’s pea exports are down in 2018/19 on lower supplies. From July through March, it exported 881,000 MT of pulses (peas, chickpeas and lentils), down 22% over the same period the previous cycle (1,132,400 MT). Total exports for this marketing year are projected to end up between 1.1 million to 1.2 million MT, compared to the 1.58 million MT of pulses it exported in MY 2017/18.

A Similar Story in the Ukraine

In Ukraine, as in Russia, pulse plantings were up in 2018, but production was down. At 565,000 hectares, pulse plantings were up 12% over the previous year, but production fell off by 23% on lower yields. In the case of peas, the major pulse crop grown in Ukraine, yields fell by 30% on low moisture levels, resulting in a drop in production from 1,098,000 MT in 2017 to 775,000 MT in 2018.

Other pulses, however, saw their production increase in 2018 due to the expansion in the overall pulse area. Ukrainian farmers harvested 54,000 MT of chickpeas and 20,000 MT of lentils in 2018, up 176% and 70% respectively over the prior year.

Notably, despite the decrease in pea production, Ukraine’s exports remained at historically high levels. From July through April, Ukraine exported 630,000 MT of peas, just 13% behind the record high 725,000 MT it exported over the same period the previous marketing year.

Its top export destinations, however, changed. India and Türkiye were the top destinations for Ukrainian peas in 2017/18, but in 2018/19, shipments to those destinations decreased by 63 and 68%, respectively. The EU emerged as the top buyer in MY 2018/19, taking 265,000 MT of Ukrainian peas, a more than threefold increase over the 85,000 MT it took in MY 2017/18. Spain was the top EU buyer, taking nearly 70% of the Ukrainian dry peas imported into the EU.

Besides the EU, MY 2017/18 saw Ukrainian peas make substantial inroads in growing markets, including Bangladesh, Yemen, Nepal and the UAE.

But despite this success in export markets, UkrAgroConsult reports Ukraine’s pea plantings are down in 2019 to 295,000 hectares, a 48% reduction from a year ago. This drastic decrease in seeded area is attributable to last year’s discouraging yields as well as lower returns to growers compared to the major grain and oilseed crops.

Based on this seeded area, UkrAgroConsult is forecasting Ukraine’s 2019 pea crop at 680-700,000 MT, down 10% from a year ago.

In fact, UkrAgroConsult projects the Black Sea region’s overall pea production falling in 2019, as Russia reduced the area it seeded to peas, as well.

Lentils from Kazakhstan

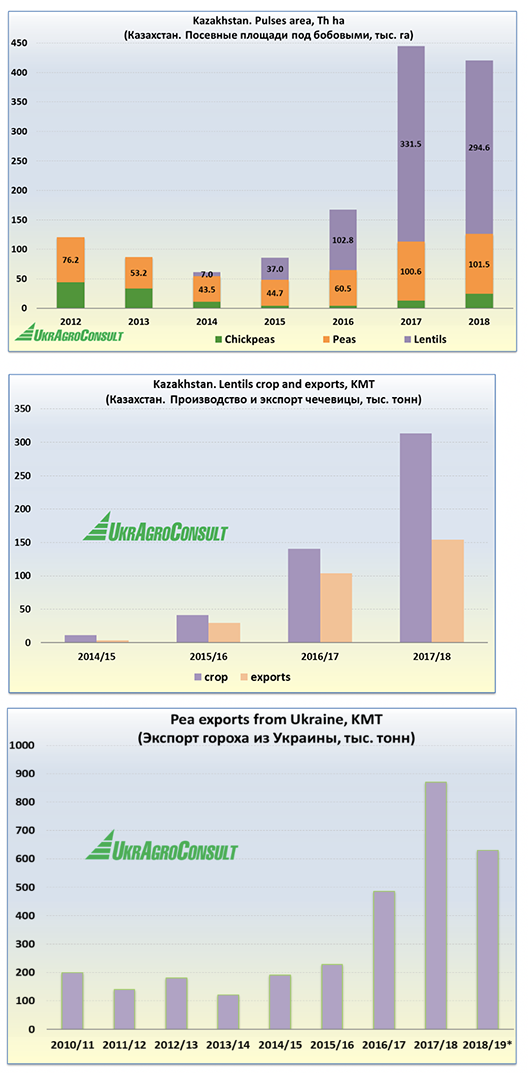

In Kazakhstan, it is lentils rather than peas that have experienced a boom in recent years. Although lentils have lower yields than other pulses such as peas, Kazakh growers began showing greater interest in this crop due to a set of factors that included attractive prices and the competitive edge that comes from their proximity to the major lentil import markets of Türkiye and India.

From 2014 to 2017, Kazakhstan’s lentil plantings exploded from a mere 7,000 hectares to 331,000 hectares. By 2016, lentils had displaced peas as the country’s main pulse crop, with more hectares seeded to lentils that year than to peas and chickpeas combined.

For 2019, however, the Agriculture Ministry reports a decrease in pulse crop plantings, with the lentil area dropping from 294,600 hectares in 2018 to 189,200 hectares in 2019. Similarly, the pea area is expected to contract to 90,900 hectares from last year’s 101,500 hectares.

UkrAgroConsult attributes the decrease in Kazakhstan’s pulse plantings to several factors. Chief among them are last year’s poor yields, disappointing returns to growers, the country’s failure to capitalize on its full potential as a pulse exporter, burdensome carryover stocks and decreased demand from the top import markets.

Disclaimer: The opinions or views expressed in this publication are those of the authors or quoted persons. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Global Pulse Confederation or its members.