August 7, 2019

With India’s withdrawal from the market, Tanzania’s pulse industry looks to its roots to secure its future.

In 2016, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi visited Tanzania, bringing with him the promise of a greater partnership between the two nations, including enhanced bilateral trade. In a press statement issued during his visit, he specifically mentioned the opportunity for Tanzania to boost its pulse exports to India. This was at a time when India’s pulse production was still recovering from the widespread drought of a few years earlier, and the South Asian giant was importing pigeon peas at record levels. In 2015, India imported 5.4 million MT of pigeon peas. By the end of 2016, that volume would hit 6.2 million MT.

For Tanzania’s pulse industry, Prime Minister Modi’s announcement was timely. By then, the International Trade Centre, an intergovernmental organization mandated by the WTO, had been working in Tanzania through its SITA project (Supporting India Investment and Trade for Africa). The project had identified the pulse value chain as one with great potential and, together with the government of Tanzania, it developed the Value Chain Roadmap for Pulses. The roadmap banded the nation’s pulse sector together and laid out a strategy for it to realize its promise. To implement that strategy, the industry created the Tanzania Pulses Network and recruited a young market monitor to lead it.

“Back then I was working part-time for a regional organization called the Eastern African Grain Council,” recalls Zirack Andrew. “My job was to monitor the price of various grain commodities. After just a few months there, I was approached by people from the pulse sector who were impressed with my work and offered me the executive position for what at that time was an informal, loose network.”

The position would be unpaid to start, but Zirack was intrigued by “the promise this sector held for the people and for the country.” Brimming with optimism, he left his part-time job and became the TPN’s national coordinator in 2017.

That very harvest season, he would witness firsthand the devastating impact that India’s policy reversal had on his country.

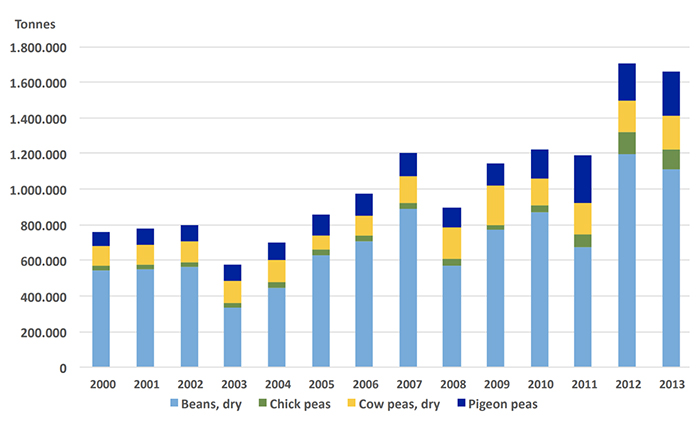

Source: FAO (2015). Statistics database.

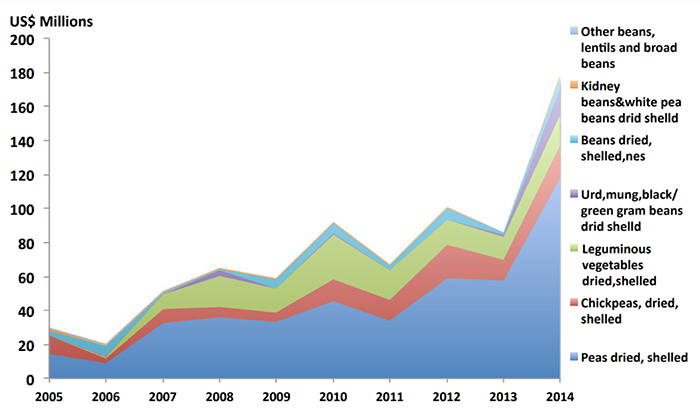

Source: ITC Trade Map

Zirack: There are five main pulse crops that are produced commercially here: dry beans, pigeon peas, chickpeas, green gram and cowpeas. All are grown in arid and semi-arid lands, and 95% of the country’s pulse crops are produced by smallholder farmers.

The growing season varies by pulse crop. The green gram crop is planted in December and harvested in March/April. The chickpeas and dry beans are planted in April and harvested in August/September. And the pigeon pea crop is mostly planted in January/February and harvested in August/September.

In terms of production volume, I would say Tanzania produces about 2 million MT of pulses per year. The latest statistics from the Agriculture Ministry are from 2016. That year, the Ministry reports dry bean production at 1.3 million MT. But that has been growing and I would guess it is at 1.5 million MT today. Yellow beans account for 60 to 65% of that production. For cowpeas, average production is 50-60,000 MT. Pigeon pea production was 160,000 MT in 2016, and is probably around 150,000 MT today. Annual chickpea production is about 80,000 MT and green gram production at around 90,000 MT.

Zirack: Domestic consumption of pigeon peas, chickpeas and cowpeas is limited. I would say more than 90% of production is exported. On dry beans, there is good internal consumption, with 68% consumed domestically and the remainder exported to other African markets, the Middle East and Europe.

In Tanzania, people eat beans every day. Per capita annual consumption is about 19kg. The preferred bean type is the local yellow bean. People also eat red kidney beans, but not to the same extent, so most of the production is exported.

But a century ago, things were different. Pigeon peas and chickpeas were originally produced in India and East Africa. But when the British colonists arrived in the 19thcentury, they found that these crops were not produced in sufficient quantities to feed the labor force they needed for their infrastructure projects, such as building the railways and supporting their armies. So they imported maize and dry beans from Mexico and used those crops to feed their colonies. Over time, the locals who worked for the British developed a taste for those crops, and when they went back to their villages, they started farming them instead of pigeon peas, cowpeas and chickpeas.

Zirack: Originally, the TPN was established to monitor the implementation of the strategy laid out in the Value Chain Roadmap. But as it developed, our members, which include all the players in the value chain, from farmers, traders, processors and service providers, they all realized that the TPN needed to go beyond that in order to serve their needs. Our work now includes, but is not limited to, creating market linkages and advocating for policy.

Presently, TPN is focused on two main goals. One is to increase productivity. Tanzania is a leading pulse producer in Africa and the world. We rank 12thin pulse production, but 112thin pulse productivity. To address this, we are providing education to farmers on the best agronomic practices, and assuring that inputs, like fertilizer and seeds, are available to them.

The other is to make sure Tanzania’s trading system for pulses is well structured. This means making sure every player involved in the trade, especially traders, are well positioned, and that the whole value chain is well coordinated.

Zirack: To put it in context, it is important to recall that in Tanzania we were encouraged to ramp up production and assured that the Indian market would be there. In 2015/16, this drove up pigeon pea prices from 1,500 to 4,500 shillings/kg. That encouraged a lot of people to get involved. Farmers planted more, traders bought farms to produce more, and we saw a huge increase in production.

When India closed its market, we were at harvest and prices here just collapsed, from $2 USD/kg to less than 20 cents/kg. At the Tanzania Pulses Network, we hired a consultant to conduct an analysis of the losses that could be attributed to this unilateral import ban. And we came to realize that 100 billion-shillings worth of pigeon peas were left out in the fields. That’s equivalent to $45 million USD. The crop was just left there because the cost of harvesting and storing the pigeon peas was greater than what farmers could earn selling it.

We surveyed one of the country’s leading pigeon pea producing districts, Masasi, in southern Tanzania. The previous year the district had collected 300 million shillings ($130,000 USD) in levies from pigeon pea trading. In 2017, they only collected 1 million shillings.

And then there was the impact on pulse companies and traders. One member of our Network invested more than $1 million USD in pigeon pea processing machinery and export facilities, not to mention the labor force required to clean, store and transport the product, and we are just talking about one case.

So the loss was massive and hit everyone in the sector, as well as affiliated services and the government, because of lost revenues.

Since then, grower interest in planting pulses has been seriously affected. Based on a survey I conducted, pigeon pea production could be down 20 to 30% this year. Everyone is skeptical about investing money to produce a crop that may not be marketable.

Zirack: There is always the possibility of finding new export markets, but we are not that optimistic there because India is such a dominant player when it comes to pulses. So we decided to turn to our domestic market. We started working with the government to promote domestic pigeon pea consumption, and we trained students here in Tanzania on the best way to prepare them, teaching them various pigeon pea recipes. For instance, we are making biscuits and buns with pigeon pea flour, and samosas stuffed with pigeon peas instead of the more customary meat and potatoes.

One of the leading reasons why people in Tanzania don’t eat pigeon peas is that we don’t know how to prepare good dishes with them. So we have been partnering with several nutrition specialists to spread this knowledge.

The idea is that increased domestic pulse consumption will help us in the long-term without losing sight of developing new market linkages in Europe and southern Africa, where there is pigeon pea consumption.

Zirack: Yes, it is going back to our roots. Its telling people that this is not a strange product. It comes from our land and eating pigeon peas is eating something that is traditionally ours.

We are following the same path the British did 100 years ago. We are approaching schools, universities, military bases, church congregations, and with their help we hope to return to what used to be our own culture.

Disclaimer: The opinions or views expressed in this publication are those of the authors or quoted persons. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Global Pulse Confederation or its members.