March 17, 2022

Speaking with Luke Wilkinson, Federico talks us through his tried and tested Speed Breeding system, and the myriad benefits it can bring.

Research into the development of new varieties of crops has intensified over recent years with a rush to find hardier, more productive strains of existing plants. Argentinian agronomist and researcher Federico Cazzola, a Doctoral Fellow in Agronomy at CONICET (Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas), wants to bring Speed Breeding techniques to the pulse industry, potentially halving the time it takes to create more prosperous crops.

My research evaluates different systems for accelerating the development of green pea varieties. When I began, Speed Breeding was a very recently developed technique but I saw the potential for someone in my position to try applying it to green peas, so I got to work and it ended up becoming the main thrust of all of my research.

CONICET is effectively the organization that finances public science research in Argentina. As part of the Argentinian Ministry of Science, it is the foremost organization of public science in the country and has a hand in everything related to scientific research in the public sector.

I am from a little town in Argentina and my family and I have always had a close relationship with the countryside. My father worked for 35 years in a multinational that produces corn and he would often take me to work with him so I could see all the different processes that go on in the fields - I think that sparked an interest.

I was always asking: “Hmm, what are those researchers doing? How are they making those seeds better?” So, when I was old enough, I entered into academia and studied to be an agronomist. Then I soon realized that if I wanted to dedicate myself to plant breeding then I had better do a PhD. That’s how my academic career got started.

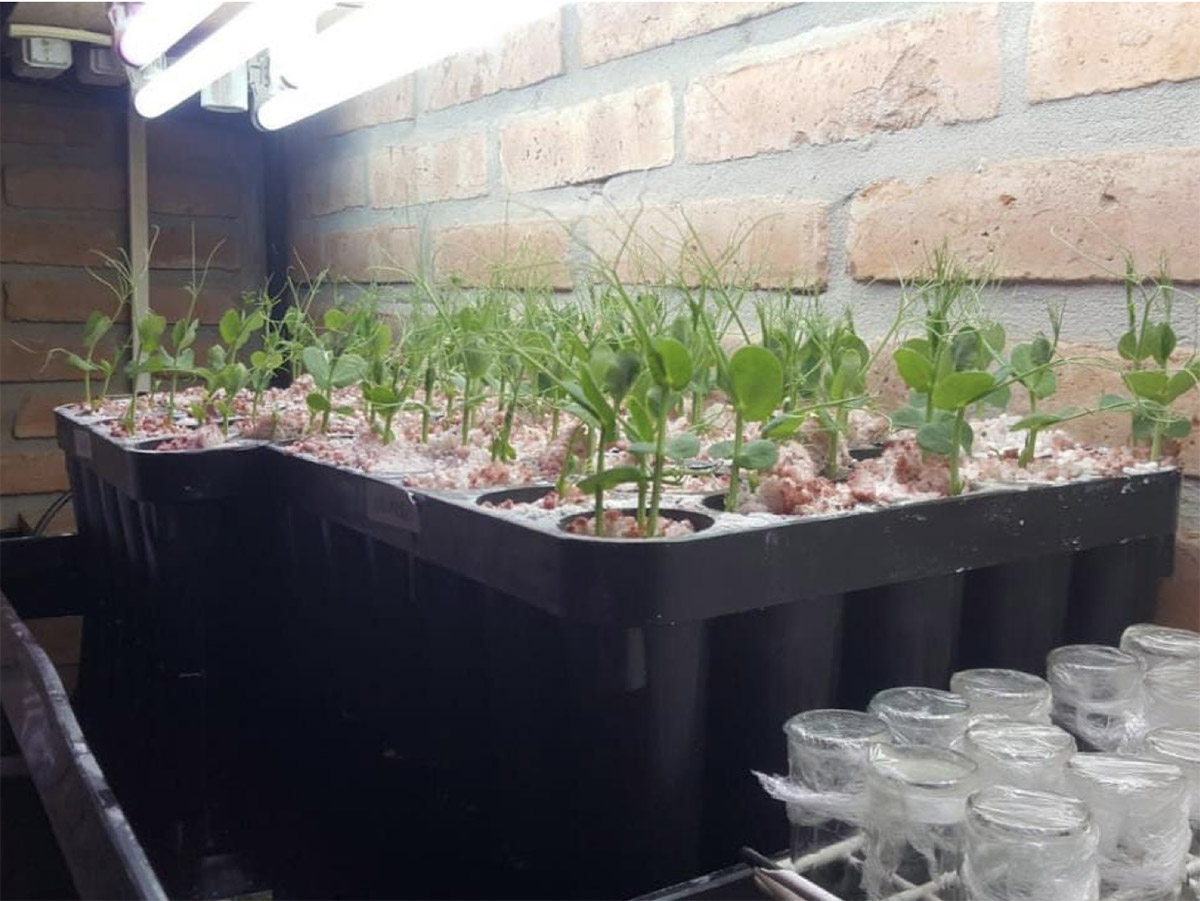

Speed Breeding is a methodology that allows us to accelerate the development of plants. This is achieved by exposing plants to optimal temperature (between 20°C and 22°C) and optimal light conditions (22 hours per day), combined with an anti-growth hormone to make the plants more compact, with a density of 266 plants per meter squared at one time in the growth chamber.

All of these factors stimulate flowering and seed production at the quickest speed possible, shortening the reproductive cycle and allowing new varieties of plants to be developed at a much faster pace by passing from one generation to the next at a much higher rate. Thankfully, recent advances in lighting systems and atmosphere control mean that Speed Breeding is now much simpler to develop and apply across the entire agricultural industry.

Generally, development of a new variety of plant, from initial cross breeding until it reaches the market, takes between twelve and fourteen years; Speed Breeding cuts the process in half - to around six or seven years. Given that we're not looking for each plant to produce a high yield, but rather a single seed as quickly as possible, everything can move a lot faster. Under Speed Breeding conditions I've been able to complete five or six full cycles in a year, as opposed to the usual one cycle a year under normal conditions.

Yes, definitely. I first tested the system using green peas and published an academic paper detailing the work and its results so it could be seen more widely. After conferring with other researchers, we soon realized the potential that the system could have for other pulses. I decided to do an in-depth study of all of the work across the world relating to the breeding of pulses in order to get a better idea of the potential of the system for use with other legumes. We started to test using lentils, which had great results, and there are other researchers working on chickpeas as we speak.

Speed Breeding is a system that is already being used with a variety of other crops, such as soy and wheat - important crops, which people have invested a lot more time and money in than pulses. Generally, pulses are a little bit behind but right now there is an explosion of demand, which makes all this research a lot more interesting.

The benefits of the system could be huge: better yields, better stability, better adaptation to the environment and higher resistance to diseases. All of these things would come a lot faster, increasing the productivity of pulses enormously.

As I say, this is something that we've already seen with wheat, soy and corn. Speed Breeding would allow for legumes to achieve the kind of genetic gains that we've seen with the other crops, bringing new varieties into the market that are much more profitable and productive.

Not yet, simply because all of this is so recent – the thesis was only finished at the end of last year. Before we could take the next step, we needed to develop the system, test it and do the necessary comparisons required for the thesis.

I couldn't tell you exact numbers, but it's not a big investment at all. You need a growth chamber, atmosphere control and growth lights – all things that most of the big companies will already have. If this was 10 years ago, it wouldn't have been feasible to adopt the system more widely because the technology simply wasn't advanced enough, but now things are much more readily available.

I've had a lot of contact with different companies and from chatting with them, it seems clear that it will be feasible to introduce the system more widely, particularly in Argentina. Right now, there are no systems in place for pulses but the fact that the programs set up for wheat have already brought results makes it clear that Speed Breeding would be both economically and productively profitable for pulses. The necessary investments are small, the systems are efficient and the benefits are huge.

Pulses have a lot of advantages, not only on a nutritional level but at an agricultural one as well. The fact that pulses fix nitrogen from the atmosphere into the soil means that there is much less need for fertilizers; they encourage diversity in production systems too, making them much more sustainable.

There is another benefit, which is particularly relevant to Argentina as, here, lentils and green beans are sown in winter. On farmland where lentils or green peas are not sown, the land would lie fallow and agrochemicals would need to be used in order to keep weeds away. If you plant legumes, you're adding another saleable crop to the rotation and you also avoid using as many chemicals.

Another reason they're important is the growing interest in plant protein. Argentina, like everywhere else in the world, is seeing an upward trend towards replacing animal protein with plant protein, a process in which pulses play a fundamental role as they contain a huge amount of protein and high-quality amino acids.

There is a large amount of energy that goes to waste here in Argentina. Take soy, which is one of our biggest crops: it gets exported to China to feed pigs at enormous energetic cost. It’s incredibly inefficient. If that protein could be replaced with plant protein, it would be fantastic at an economical level but also for the world, our ecosystem and for the sustainability of our production chains - for humanity in general!

What I would really like to do is to branch out into developing different types of pulses and setting up different breeding programs both in Argentina and all around the world. I'd like to spread these ideas further and perhaps work in Europe if the opportunity arises. Coming from a developing country means that sometimes scientific advances take a bit longer to arrive so I'd like to go to Europe to be at the forefront of these new ideas and develop knowledge and experience to bring back to Argentina.

Federico Cazzola / Speed Breeding / green pea / agronomy / lentils / Argentina / plant protein / animal protein

Disclaimer: The opinions or views expressed in this publication are those of the authors or quoted persons. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Global Pulse Confederation or its members.