January 6, 2020

The Chairman of the Myanmar Pulses, Beans and Sesame Seeds Merchants Association talks about his country’s pulse industry.

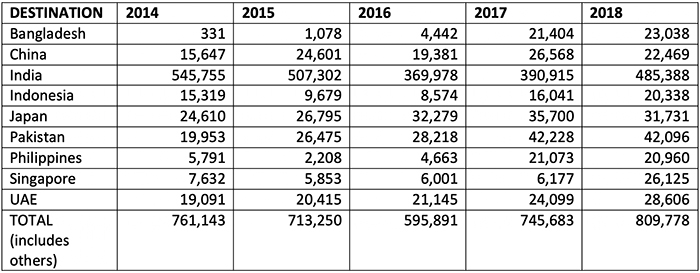

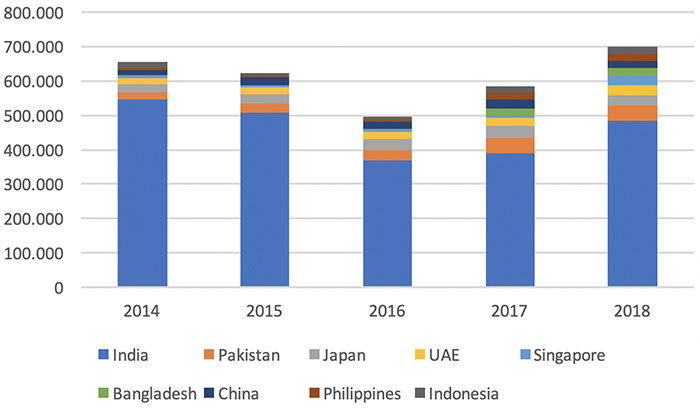

Today, Myanmar is known in pulse industry circles as India’s number one source for pulse imports. This is an envious distinction given that India is the world’s top pulse consuming and importing nation. According to official figures from the government of India, the country imported 700,000 MT of pulses from Myanmar in 2018/19. That amounts to nearly 28% of India’s total pulse imports that campaign.

The story of how Myanmar became a major pulse exporting nation is one of remarkable growth. It began in 1988, when the country transitioned from a socialist to a market economy. Pulses represented the first major agricultural sector to be liberalized, and production exploded as a result. By 1991, pulses surpassed rice as the country’s most valuable agricultural export. And in 25 short years, the pulse sector ballooned into a $1 billion export industry.

A large part of this growth was driven by nearby India’s 1991 trade liberalization, which opened its market to pulse imports and gave Myanmar’s pulse industry a golden opportunity to increase its exports. According to the India Pulses and Grains Association, the southeast Asian giant came to take as much as 80% of Myanmar’s pulse export availability. But the volume of Myanmar pulses destined for India has decreased in recent years as India pursues pulse self-sufficiency and prioritizes its domestic production.

“If India becomes self-sufficient in pulses, then Myanmar will need to seek new potential export markets and diversify into alternative crops. Arrangements may need to be worked out to safeguard the long-term interests of both nations,” says Tun Lwin, the Chairman of the Myanmar Pulses, Beans and Sesame Seeds Merchants Association. The Association was founded by pulse industry members in 1992, as pulse production and exports were beginning to accelerate.

“The Myanmar pulse industry has gone through major changes,” says Lwin. “Production shifted its focus from domestic consumption to exports, both production and exports accelerated significantly in a short period of time, the types of pulses and beans that we grow has changed in accordance with market demand, and India and China emerged as our principle destinations.”

Through it all, the Association has grown and played an important role in the pulse sector’s sustainable development by strengthening cooperation and collaboration between the private sector and various government agencies, advocating for appropriate policies and disseminating market information.

Since 2009, Lwin has been at the helm of the Association, serving five consecutive terms and steering the industry through the domestic market collapse of 2008 and the recent changes in India’s pulse import policies. His longevity at the industry’s top leadership position is a testament to his professionalism and the respect he commands among his peers.

In this interview, Lwin provides the GPC with an overview of Myanmar’s pulse industry and recaps the past growing season.

Source: Myanmar Pulses, Beans and Sesame Seeds Merchants Association

Source: Myanmar Pulses, Beans and Sesame Seeds Merchants Association

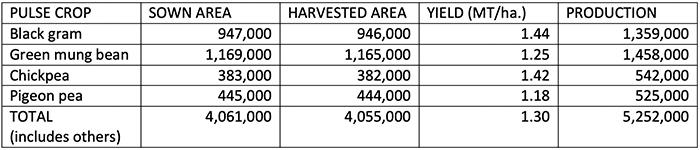

Source: Myanmar Pulses, Beans and Sesame Seeds Merchants Association

Lwin: I was born in Yangon in 1968 and graduated from the University of Yangon with a Bachelor of Science in Chemistry. In 1995 I founded the Shwe Me’ Company Limited, but it wasn’t until 2006 that, on the advice of a friend, we became involved with pulses.

The company is part of the Shwe Me Group, which includes the Shwe Me Industry Company Limited, Shwe Me Logistics Services and the Elephant Construction Group. The Shwe Me’ Company Limited is primarily focused on the export of agricultural products, and the import and distribution of construction materials, especially cement, timber processing, and providing comprehensive logistics services. We also have a teak plantation and a feed mill.

Lwin: We work with black gram and pigeon peas. We store pulses in our warehouses, where we process and package them for export to India. The Group typically processes and exports about 30,000 MT of pulses annually.

Lwin: The pulse sector established the Association in 1992, just as pulse production and exports started to accelerate as the country shifted from a socialist to a market economy. Over the years, the Association’s membership has grown, and it has become well-funded, which has allowed it to become increasingly independent and to provide broader services to its members. For instance, the Association helps resolve export-related issues and problems, it issues a Certificate of Origin, it recommends policies and regulations and it promotes the domestic consumption of pulses.

Lwin: Yes, the pulse industry was greatly impacted by the reform process following the open elections of 2015. Pulse exports expanded, a national export strategy was implemented, and a pulse sector development strategy increased cooperation with development partners. Additionally, trade barriers were lowered, and the use of information and communication technology increased.

Lwin: In Myanmar, we grow a variety of pulses, but the ones that are most important for the country’s economy are black gram, green mung beans, butter beans, cow peas, sultani, sultapya, soybeans, chickpeas, pigeon peas, bamboo beans, lima beans, lab lab beans, pegya, field peas and lentils.

Pulses are produced both during the rainy and winter seasons. Rainy season pulses are generally planted in June-July and harvested in September-October. Winter season pulses are planted in November-December and harvested in January-February.

In a typical year, pulse production ranges from 5.5 million to 6 million MT. Per capita consumption is estimated at 10 to 13 kg. and it is increasing as the population grows and consumption preferences change. For the most part, domestic production covers internal demand, but we do need to import field peas to meet local demand.

In terms of exports, the major types that are commercialized abroad are gram, green mung beans, pigeon peas, chickpeas, cowpeas, butter beans, red kidney beans, bamboo beans, bocate and penigya. In a typical year, we export 550,000 MT of black gram, 450,000 MT of green mung beans, 250,000 MT of pigeon peas and 200,000 MT of other pulses.

Lwin: This year, 4.06 million hectares were seeded to pulse crops and production amounted to slightly more than 5.25 million MT, down from 5.75 million MT last year. This year’s production includes 1,359,000 MT of black gram, 1,458,000 MT of green mung beans, 525,000 MT of pigeon peas, 542,000 MT of chickpeas and 1,368,000 MT of other pulse types.

We did have some weather issues. Some areas experienced drought while others were affected by flooding. But it could be said that the weather conditions were mostly normal.

In terms of quality, some of the crop had issues, but overall the quality is good and not much different from last year.

Lwin: Field pea imports are estimated at 50,000 MT this year, down from 300,000 MT last year. In terms of exports, we have greater availability this year. Last year, export availability was about 1.3 million MT. This year, it is estimated at 1.5 million MT. We are looking forward to a successful campaign in 2020.

Any information provided by an external source does not necessarily reflect the official position of the Global Pulse Confederation and should be verified independently.

Disclaimer: The opinions or views expressed in this publication are those of the authors or quoted persons. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Global Pulse Confederation or its members.