October 27, 2020

The EU intends to use its leadership in food safety and quality standards to effect change beyond its borders.

On October 20th, the Council of the European Union (EU) unanimously adopted a set of conclusions to move its Farm to Fork Strategy forward. The strategy, first announced this past May as part of the EU’s Green Deal, aims to develop a sustainable food system that helps the EU achieve climate neutrality by 2050 while also ensuring a reliable supply of affordable, nutritious food for its residents. As if that were not ambitious enough, it also seeks to leverage the EU’s globally recognized standards for food safety and quality to effect change beyond its borders.

The strategy was unveiled just as the COVID-19 pandemic was straining the world’s food systems. As several countries imposed national lockdowns to contain the virus, weak links in supply chains were exposed. Disruptions in shipping impacted the availability of imports at destinations while cargoes stacked up at origins. Truckers encountered delays at border crossings. And outbreaks at meat processing facilities caused them to shut down, creating a bottleneck that forced farmers to cull livestock. Similarly, the closure of restaurants and schools saw milk being dumped and mountains of food go to waste. On the consumer end of the chain, shoppers felt the sting of food inflation and hurried to stock up on non-perishable food items, especially pulses. This in turn kept distributors working overtime to stock store shelves.

In a way, the COVID-19 experience has underscored the need for aggressive action to address agriculture’s biggest challenge: how to provide enough affordable, healthy food to feed a world population expected to grow to nearly 10 billion people by 2050, and do it in an environmentally sustainable manner.

The Farm to Fork strategy is the EU’s answer. The United Nations reports that modern food systems contribute 37% of all greenhouse gas emissions. The strategy looks to transition to a food system that addresses climate change, preserves biodiversity and ensures food security, all at the same time. It recognizes, though, that the world’s environmental challenges require international engagement. The EU, therefore, intends to take a leadership role in setting the global standards that will accelerate a worldwide transition to sustainable food production. Under the strategy, those who wish to export agricultural products to the EU will be subject to the same restrictions and limitations on agrochemical use as EU farmers.

This latter point in particular has drawn criticism from some of Europe’s trade partners. The U.S. has been the most vociferous, accusing the EU of using the strategy to mask protectionist policies. During a teleconference with European journalists, U.S. Agriculture Secretary Sonny Purdue said, “The impact on transatlantic trade can be extremely problematic.” He argued: “If European farmers are restricted from using modern tools … they will have the only choice of protectionism.”

But from the perspective of the global pulse industry, the strategy has more of an upside than a downside.

The Farm to Fork Strategy emphasizes sustainability across the entire food supply system. At the production level, it aims to reduce the environmental and climate impact of growing food while also ensuring a fair economic return for farmers, improving animal welfare, protecting plant health and motivating the adoption of green business models. In terms of processing and distribution, the goal is to make healthy, sustainable food options more widely available and affordable; this includes initiatives to incentivize the reformulation of processed foods and the setting of nutrient profiles for food products (ie., high salt, sugar or fat content). And last but not least, on the consumer side the strategy seeks to promote the adoption of healthy and sustainable diets via mandatory food labeling, traceability requirements and the setting of criteria to drive the institutional procurement of sustainable foods, including organics.

At Casibeans, a third-generation family run busines based in Belgium and specializing in pulses, General Manager Caroline Suy is upbeat about the overall impact of the strategy on the EU.

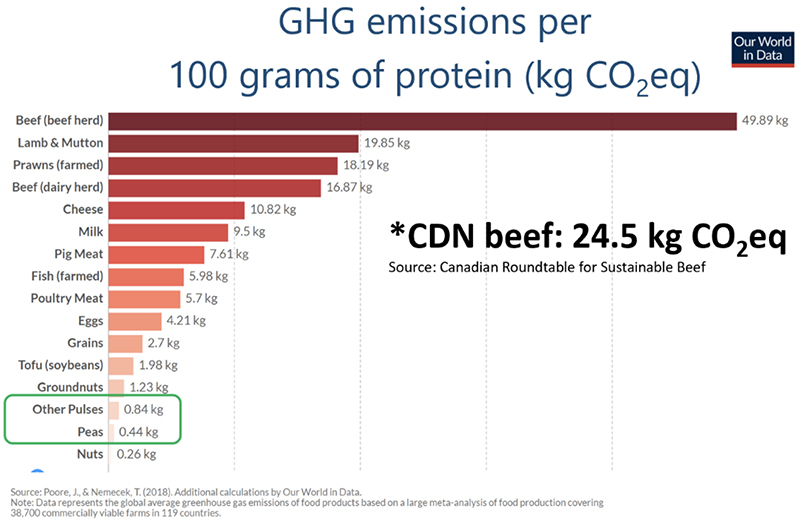

“Its very simple,” she explains when asked why. “Pulses are a perfect fit when it comes to the Farm to Fork Strategy. On the environmental side, they are water efficient crops and, because they fix nitrogen in the soil, they don’t require chemical fertilizers, contributing to greenhouse gas emission targets. Then on the health side, they contribute to a balanced diet and are rich in protein and essential minerals and nutrients.”

Pulses, the main source of protein in the growing plant-based food movement, fit right in with the strategy’s call for a shift toward more animal-friendly, plant-centric diets. For Suy, Farm to Fork’s emphasis on plant-based eating translates to more pulses on European plates, creating valuable growth opportunities along the pulse supply chain.

Over in Canada, the world’s top pulse exporting country, Mac Ross at Pulse Canada also sees opportunity in Farm to Fork. At a time when pulse ingredients such as pea protein are seeing phenomenal growth, he points out, “The sustainability benefits of pulses can be a great differentiator with other ingredients out there.”

As Ross sees it, there is an opportunity to produce great synergy between the EU’s Farm to Fork Strategy and Pulse Canada’s 25 by 25 Initiative, which aims to redirect 25% of Canada’s pulse production to new markets and new use categories by 2025.

“The EU is a big part of that with their focus and demand for more sustainably grown foods,” he says.

The 25 by 25 Initiative is well on its way to meeting its goal, as more and more plant protein extraction facilities are being built in the Western Prairies. In fact, France-based Roquette is set to inaugurate the world’s largest pea protein plant in Manitoba later this year.

“Globally everyone is coming to the realization of the inherent sustainability benefits that pulses have,” says Ross. “We have done work on completing lifecycle assessments on Canadian pulses to actually show and quantify the sustainability value of including Canadian pulses and pulse ingredients in an end use product.”

To drive this point home, Pulse Canada is quantifying sustainability metrics and developing graphics that illustrate not only the sustainable benefits of pulses, but also their health and nutritional benefits. For instance, a comparative analysis of an all-beef burger with a blended beef/lentil burger found that substituting 33% of the beef with lentil puree reduced the burger’s saturated fat and cholesterol content by 32% and 33% respectively, and upped its fiber and folate content by 50% and 127%.

In this regard, the EU’s Farm to Fork Strategy plays to the intrinsic strength of pulses, making them an easier sell.

But, Suy reminds us, “In any transition, there are always challenges to overcome.”

Graphic courtesy of Pulse Canada.

For the pulse industry to seize the opportunities Farm to Fork offers on the marketing side, it will need to address some challenges on the production side. The Farm to Fork Strategy envisions reducing the use of chemical pesticides by 50% by 2030. It also calls for a 20% reduction in fertilizer use, a target that should incentivize the growing of nitrogen-fixing crops such as pulses. This is one of the reasons, together with the push for plant-based diets, why Suy expects the transition to be easier for actors in the pulse supply chain as opposed to those in other ag sectors.

“In the case of the EU,” says Suy, “actors in the supply chain will have to innovate and adjust their current practices to accommodate the Farm to Fork Strategy and the underlying needs of society, the plant and end consumers. Putting targets and timelines in place are the key to enabling companies to make the transition.”

The strategy’s restrictions on agrochemical use will apply not only to European farmers, but also to those at other origins who intend to supply European markets. Across the Atlantic, Pulse Canada’s Ross sees this aspect of the Farm to Fork Strategy as concerning, albeit expected.

“Pulse Canada supports Farm to Fork’s sustainability objectives,” he says, “but it has some concerns about unintended consequences that might come from forcing change to happen too quickly and independent of integrated pest management assessments and risk assessments, especially since the intent is to also impact farming practices outside of the EU.”

“We recognize the need for movement here,” he continues, “but in our experience, evidence- and science-based policy is needed to bring about timely, positive change. We really want to ensure we are not removing the use of tools and technologies that may help us achieve our global, environmental and sustainability goals.”

He cites the example of the use of certain pesticides in Canada that have allowed the farm sector there to adopt a more carbon-friendly cropping system with minimum tillage.

“One thing that the COVID-19 experience has taught us is the importance of food security, and a major component of that is affordability,” says Ross. “Our modern food systems have allowed us to produce food and pulses that are not only safe, sustainable and nutritious, but also affordable. That has to be a consideration and that gets back to why some of these ambitious goals to restrict the use of certain technologies must be based on science and internationally accepted protocols.”

In Argentina, another of Europe’s major pulse suppliers, the reaction to Farm to Fork is similar. In a nation of beef eaters, practically the entirety of the country’s pulse production is destined for export markets, and Europe is an especially important destination. What happens in Brussels, therefore, has profound implications for the country’s pulse sector.

Sergio Raffaeli, president of CLERA (Argentina’s Chamber of Pulses), began to take notice of agrochemical-use restrictions at its major export markets, chiefly Europe, about three years ago.

“We understood at that time that if Europe stood firm on the matter, other countries would follow, and that is what happened,” he says.

Today, in anticipation of a likely EU ban on glyphosate in a matter of years, the pulse sector is looking to phase out its use as a desiccant. Instead, CLERA is exploring the effectiveness of having pulses cut and left in windrows to dry naturally in the fields. Similarly, it is exploring alternatives to chlorpyrifos and neonicotinoids, pesticides that have been banned in the EU.

“One thing we are looking at is the development of microbial pesticides, insecticides and fungicides,” says Raffaeli. “For example, research is being done on bacteria that inhibits fungi like white mold.

To make sure it has all its bases covered, CLERA is in the process of compiling a registry to identify other agrochemicals that are used in Argentina but banned or restricted in Europe.

The South American country has an interesting history with agrochemical use. From the early ’90s through to the first decade of the new century, the ag sector there was heavily reliant on spraying chemicals to control weeds, insects and disease. Soybean production was king at the time and it was the soy sector that first started to realize this was a mistake: the intended targets of the agrochemicals were building up resistance and becoming superweeds and super-insects.

“It was that experience that led the sector to explore combining chemical and biological controls,” recalls Raffaeli. “And what we discovered is that not only did control methods became more efficient, but input costs decreased.”

In Argentina, therefore, it was agronomic and economic considerations, rather than environmental ones, that motivated growers to cut back on agrochemical use.

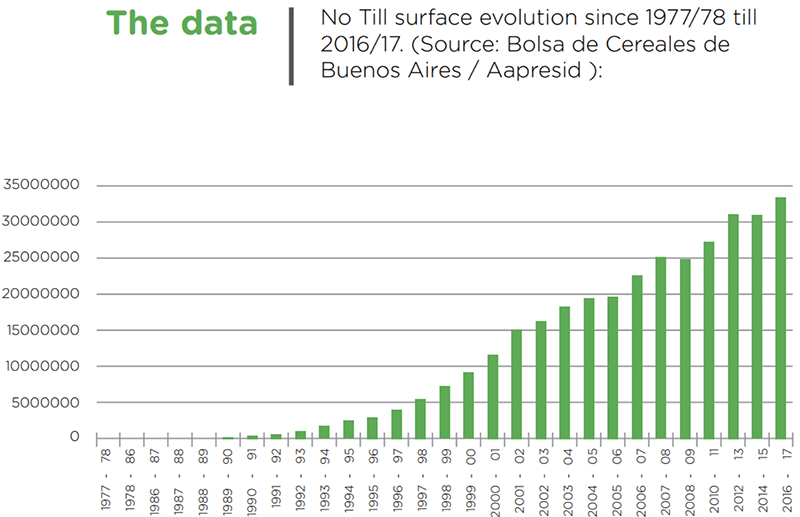

Around the same time, another important shift was taking place in the nation’s agriculture sector. In order to address the issue of soil erosion, Argentine growers increasingly adopted no-till farming.

“Today, no-till farming is practiced on 95% of the nation’s farmland,” says Raffaeli.

In addition to preserving the soil, the practice also converts cropland into a carbon sink. What’s more, by creating a buffer of organic material, it keeps agrochemicals from filtering into the groundwater. And the canopy created by the stubble from previous crops blocks sunlight and lessens the incidence of weeds.

“In terms of Farm to Fork, we are halfway there,” says Raffaeli. “We just need to reevaluate our agrochemical use and bring it in line with EU standards.”

He is optimistic that in two to three years, Argentina will be aligned with the demands of the EU market and have new crop management practices in place as well as traceability systems that will make compliance transparent.

Graphic from Argentine No till Farmers Association (Aapresid) report titled “Update! Evolution of No Till Adoption in Argentina” by Santiago Nocelli Pac, page 4.

In many respects, the EU’s Farm to Fork Strategy taps into many of the same trends the global pulse industry has identified. From the move to plant-based diets to the adoption of sustainable agricultural practices, pulses are front and center.

A Meticulous Research report projects the plant-based food market will experience a CAGR of 11.9% from 2020 to 2027, reaching $74.2 billion by then. Within that market, the pea protein segment is poised to see the fastest growth as the preferred alternative to animal protein.

Meanwhile, as the impacts of climate change become increasingly evident and water resources are strained, it is clear that there can be no food security without sustainable agriculture. In that respect, pulses, thanks to their nitrogen fixation properties, low water use and small carbon footprint, are finding a permanent spot in crop rotations.

“Farmers in Canada as well as in the EU, and really all around the world, deal with similar challenges of climate change, soil fertility, agronomic pressures and farm profitability,” says Ross. “Farmers continue to evolve their practices through the adoption of new technologies to provide healthy and nutritious food, and use resources more efficiently and just improve overall sustainability.”

“In the pulse industry, we always knew where we were headed,” says Suy. “The Farm to Fork Strategy is the roadmap to get us there.”

Disclaimer: The opinions or views expressed in this publication are those of the authors or quoted persons. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Global Pulse Confederation or its members.