February 9, 2023

Whether dried, canned, curried or pureed, chickpeas are rapidly taking a stake in the UK’s sustainable and health-conscious dinner plate - according to National Diet and Nutrition Survey Results.

Once a pulse exclusive to Asian and the Mediterranean cuisines, chickpea consumption has been found to be increasingly present in the UK market in recent years. In the new British Nutrition Foundation webinar, Pulse Power, Dr Samara Joy Nielsen, the Principal scientist at PepsiCo R&D, discussed the findings of the National Diet and Nutrition Survey’s (NDNS) comprehensive rolling programme on UK health from 2008/09 to 2018/19, in relation to its conclusions on chickpea consumption.

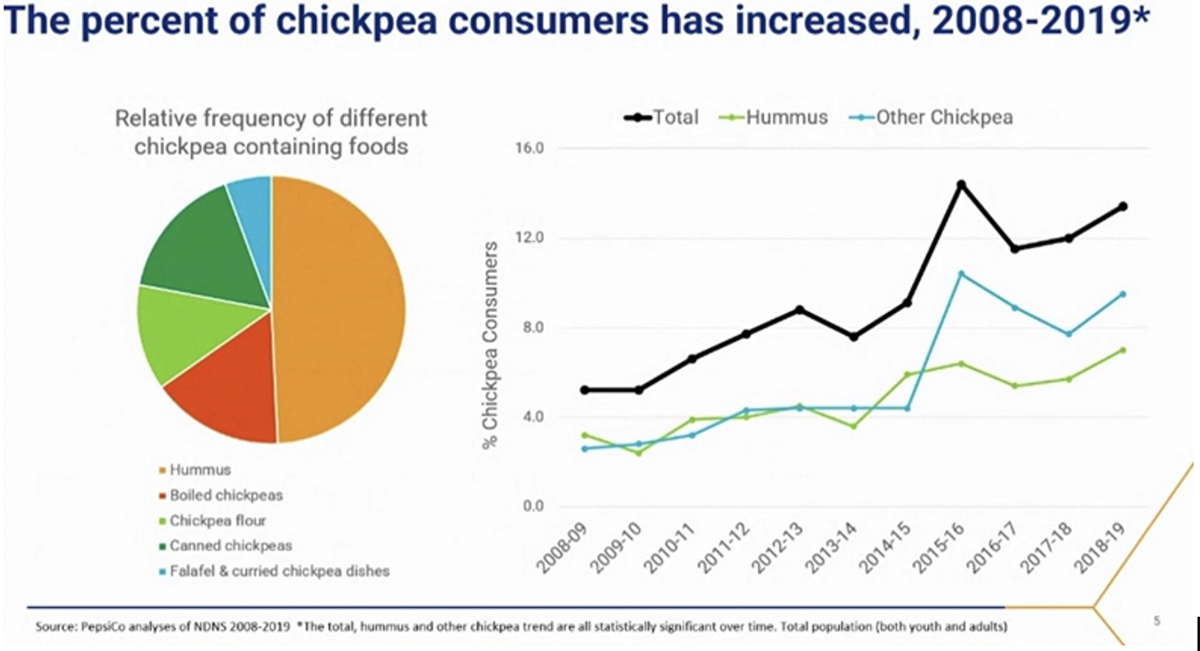

Looking at the food diaries kept by around 1000 UK respondents on four randomly allocated days, the total increase in chickpea consumption went from 5.3% in 2008/09 to 13.4% in 2018/19.

The defined forms of chickpeas that were recorded included, hummus, boiled chickpeas, chickpea flour, canned chickpeas, and falafel and curried chickpea dishes. Hummus was found to be the most popular form overall, accounting for 49% of consumption. The distinction of hummus in the UK is significant as the region accounts for 43% of overall market growth across Europe, currently valued at $321.34 million according to a Technavio Research report.

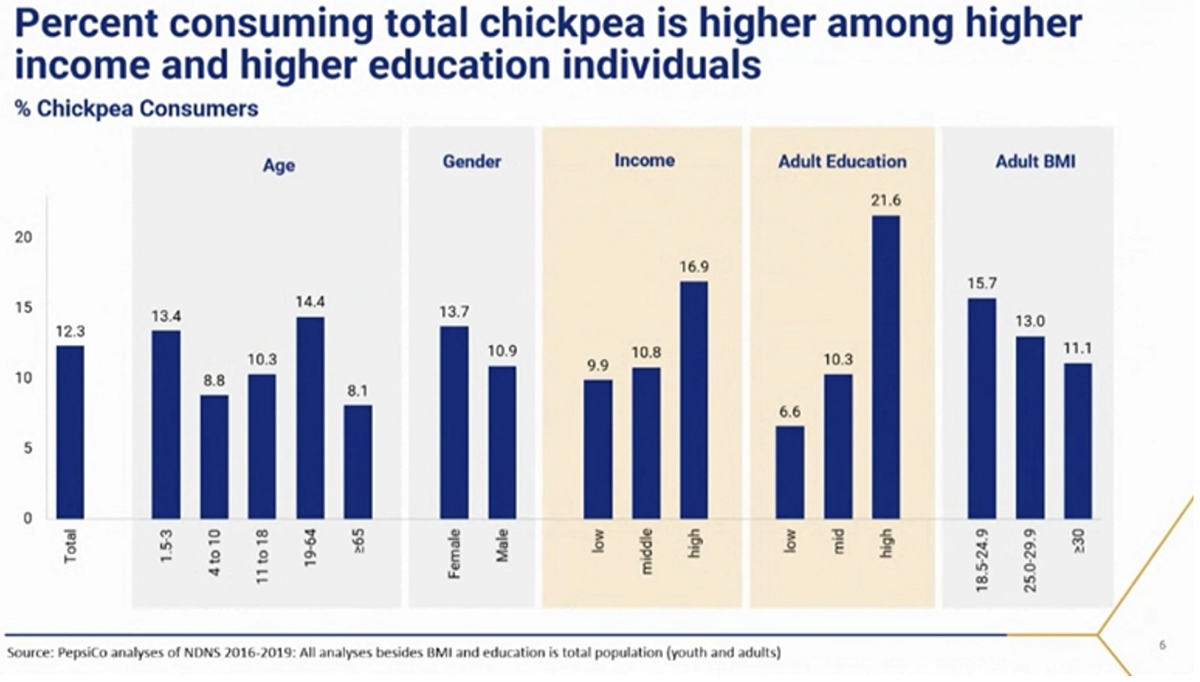

Respondents in the NDNS survey were differentiated across age, gender, income, adult education, and adult BMI - revealing growing demands across age groups and wide socioeconomic variation. Focusing on the back end of the survey, from 2016 to 2019, Dr Nielsen revealed that children aged 1.5 to 3 accounted for 13.4% of chickpea consumers, this was only bested by people in the 19-64 range by 1% (14.4%) - respondents among the 4 to 18 and over 65s made up around 9% respectively.

“You might have an idea in your mind that probably most of those people (respondents) are adults, which is what we thought when we started this research project,” explained Dr Nielsen, regarding the assumption her team initially made about chickpea consumption. “It is not just adults that are consuming chickpeas.”

Most interestingly, the presence of chickpeas is most prominent in the diets of respondents with a higher income and higher level of education. The above graph shows that people on a higher income (though the specificities in income are not disclosed) made up around 19.6% of chickpea consumption on average, 6.1% higher than those of a middling income (10.8%) and 7% higher than those on a lower income (9.9%).

“It is not just adults that are consuming chickpeas.”

In tandem with this data and by far the largest discrepancy in results found was in the education level among adults. Respondents with a higher level of education made up 21.6% of adult chickpea consumption, on average eating more than people of mid-level education by 11.3% (10.3%) and low-level education by 15% (6.6%). Compounding this data with that of the higher income variables, it typifies the consumption of chickpeas as an exclusive food product that is not widely accessible to those of lower socioeconomic backgrounds.

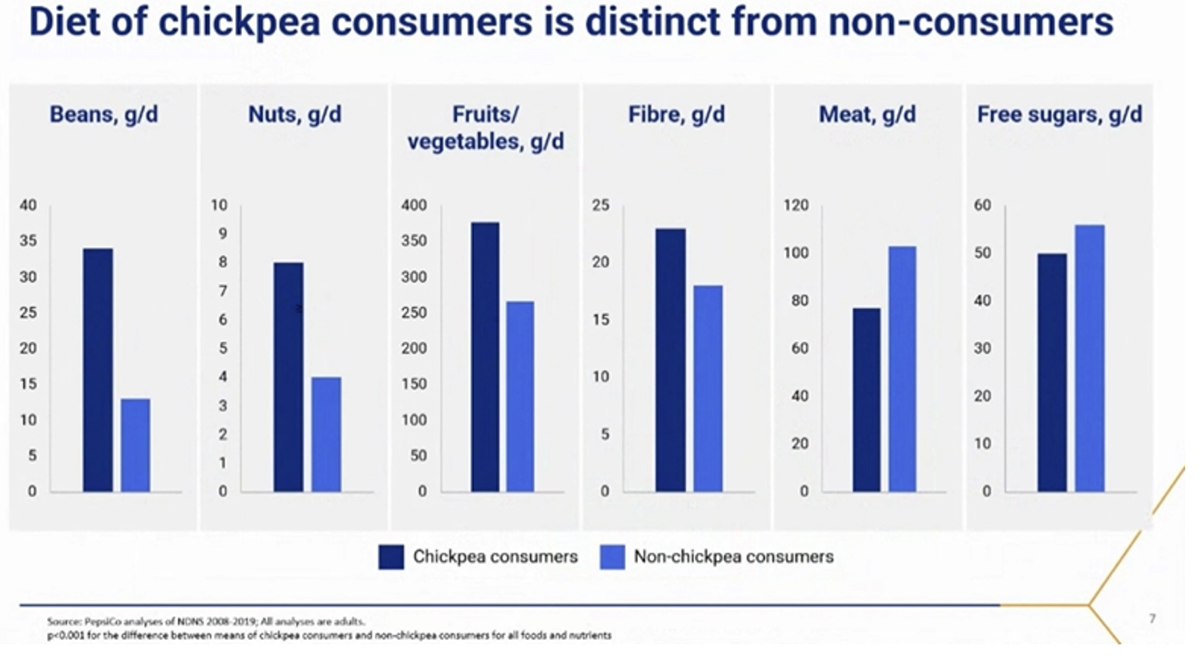

More broadly in the NDNS results, it was found that respondents who did consume chickpeas, also consumed a higher percentage of beans, fruits and vegetables, and a lower percentage of meat and free sugars compared to non-chickpea consumers. This data concludes that on average, the population that does incorporate chickpeas into their diet, are also more likely to rely on other plant-based sources of nutrition.

Again, the findings from this survey bring up further evidence that suggests people with higher levels of income and social class have access to better sources of nutritious and fibre-intensive foods. This brings the question of how accessible this crop of pulses is to the wider public in the UK.

The evidence suggests that people with higher levels of income and social class have access to better sources of nutritious and fibre-intensive foods.

An average can of chickpeas ranges from 50 pence to £1.00 in select UK supermarkets like Tesco and ASDA, with hummus falling around the £1.00 to £1.50 mark. What may be a factor in this socioeconomic gap in consumption is the relative newness of chickpeas on the UK agricultural scene.

The UK has not been a significant producer or supplier of chickpeas, itself relying largely on imports from India, the United States, and Australia. According to export and import data provider, Volza Grow Global, these imports come mainly in roasted form.

However, this global hegemony may soon change, as UK farmers have started to produce chickpeas commercially. In 2019, up to 20 tonnes of kabuli and desi chickpeas were harvested for the first time across four farms in Norfolk - with this, the rise in UK exports has also increased steadily, with 2,786 tonnes being produced in 2020.

With this upsurge in homegrown crops, the demand for chickpeas may become more stable across income and class lines, further incentivizing UK consumers to incorporate chickpeas into their everyday diets. Likewise, where demand goes, resources flow, meaning UK growers could be increasingly interested in cultivating chickpeas.

Disclaimer: The opinions or views expressed in this publication are those of the authors or quoted persons. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Global Pulse Confederation or its members.