December 4, 2019

Widespread flooding and infrastructure damage reported in key pulse-growing states.

Photo courtesy of Eleazar Cota, Bodega de Granos el Alazan y el Rocio.

Late last week, torrential rains hit Mexico’s pulse growing region just as farmers were sowing their fall-winter crops. In Sinaloa, Sonora and Baja California, news reports (see here and here) indicate that, in less than 48 hours, more than a 100 mm of rain fell in in several municipalities, causing widespread flooding, damaging homes, necessitating school closures and leaving roads and bridges in disrepair. Eleazar Cota of Bodega de Granos el Alazan y el Rocio informed GPC that on the coast of Hermosillo, more than 50 mm of rain fell over a span of just 30 hours.

The pulses planted during the fall-winter cycle include both chickpeas and dry beans. Chickpeas are grown almost exclusively during this time of year. Dry beans, on the other hand, are mainly produced during the spring-summer cycle. This year, however, drought conditions at that time of the year led to reduced production and the expectation that growers would see an opportunity there and seed 100,000 hectares to dry beans this fall-winter cycle. However, according to Felipe Sandoval of BeGrait International, a scarcity of moisture, high seed prices and limited financing limited fall-winter dry bean plantings to some 50-60,000 hectares.

Of the two pulse crops, both Sandoval and Cota assess that the dry bean crop was hit hardest by the late November rains. Below, we take a closer look at each.

Photo courtesy of Eleazar Cota, Bodega de Granos el Alazan y el Rocio.

Cota reports that at the time that the rains came, chickpea seeding was not that far along. Because of low chickpea prices, growers were debating whether to plant corn instead. Consequently, as of last week, Mexico had only seeded about 9,500 hectares to chickpeas.

In Sinaloa, the planting window for chickpeas closes December 5th, well before the close of the corn planting window (which is in late December). With the fields now waterlogged, it appears Mother Nature made their planting decision for them.

“Fields are underwater, roads are impassable,” explains Cota. “For the most part, there is no time to re-seed and by the time they get back in the fields, it will be too late to plant more chickpeas. I think the chickpea area will be at a historic low.”

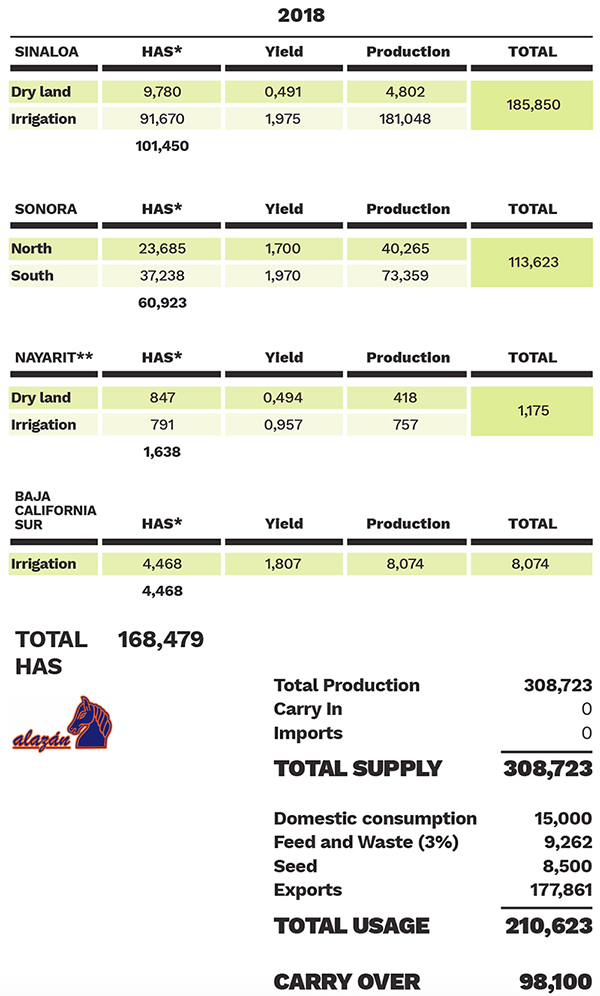

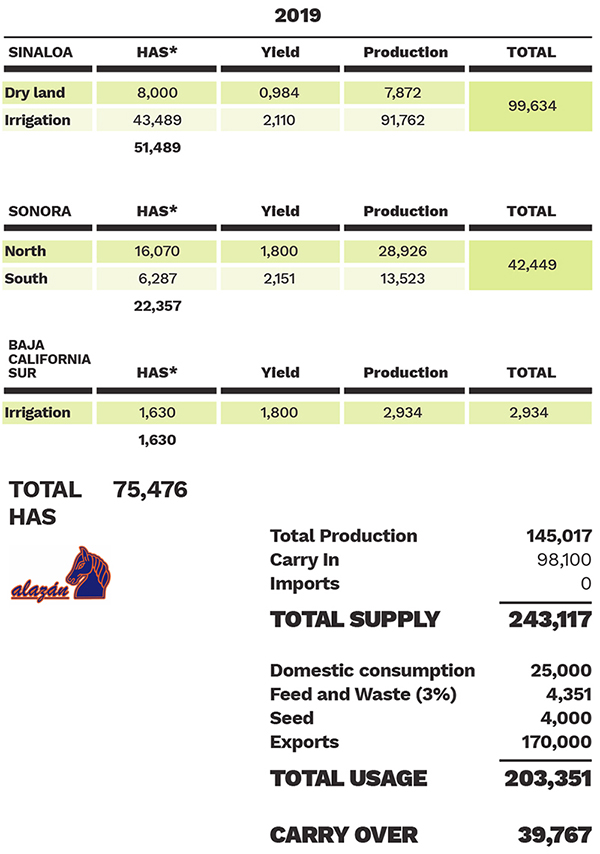

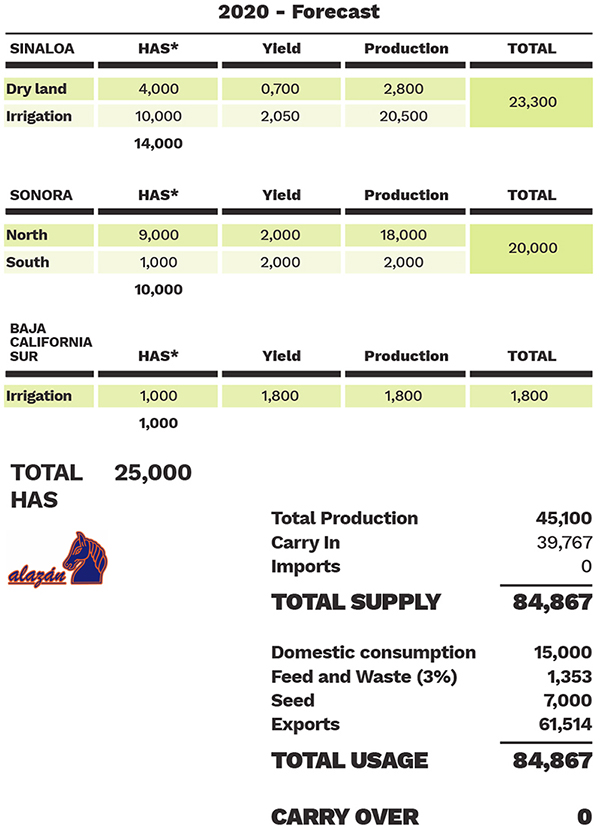

Industry sources expect the chickpea area will end up somewhere between 25,000 and 35,000 hectares. That’s down from 75,476 hectares the previous fall-winter cycle.

Cota foresees Sinaloa seeding 10,000 irrigated hectares and 4,000 rainfed hectares to chickpeas. In Sonora, the planting window for chickpeas runs through December 30th. Cota expects there will be an additional 8-9,000 hectares seeded to chickpeas there and another 1,500 hectares in Baja California.

All told, he estimates only about 20-25,000 hectares will be seeded to chickpeas nationwide. Based on his overall area estimate, Cota projects Mexico’s 2019/20 chickpea production at no more than 40-45,000 MT.

“And that’s assuming average yields,” he qualifies. “Given all the rain, we are probably going to end up with below average yields.”

Mexico’s 2019/20 chickpea crop will be supplemented by sizable old-crop inventories. Cota estimates carry-in at 40,000 MT.

Alazan chickpea balance sheet as of November 28.

An atypically high number of hectares were seeded to dry beans this fall-winter cycle as growers responded to the reduced production of the spring-summer cycle. A U.S. Dry Bean Council report on Mexican dry bean production estimates the spring-summer bean crop at approximately 400,000 MT, down from 859,000 MT the previous spring-summer cycle.

When the rains hit in late November, the dry bean planting was farther along than the chickpea seeding, and therefore the damage to the crop was greater. Sandoval points to news reports that indicate that in the area of Guasave alone, 14,000 hectares of dry beans are at risk. But the worst hit fields were farther south, in Mazatlán, where the rains were most intense.

“We are still evaluating the damage,” says Sandoval as he tours the growing area. “We have to see if the plants continue to flower or if the excess water has stunted their development.”

In addition to drown outs, the excess moisture has also elevated the likelihood of disease issues. Fall-winter crops are normally harvested in March. The GPC will continue to follow developments.

Photos courtesy of Felipe Sandoval, BeGrait International.

Disclaimer: The opinions or views expressed in this publication are those of the authors or quoted persons. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Global Pulse Confederation or its members.