July 7, 2020

What is behind the country’s renewed appetite for a forgotten food staple?

Cooking demonstration during 2019 Dal Festival.

Throughout the world, consumers are becoming increasingly aware of the health, nutritional, environmental and ethical ramifications of the food choices they make. In the U.S., for instance, the Plant Based Food Association indicates 29% of consumers identify as flexitarian and 30% of millennials indicate they are trying to eat more plant-based foods. Late last year, in recognition of the momentum behind this shift in dietary preferences, Innova Market Insights dubbed the plant-based revolution as one of the top trends of 2020.

Yet for many of the world’s culinary traditions, the move towards plant-based eating is more aptly described as a renaissance than a revolution. The United Kingdom is a case in point. Beans and peas were once staple food items there. But with the advent of the Industrial Revolution and the discovery of novel methods to preserve meat and dairy, animal protein became widely available and affordable, and pulses fell out of favor. Today, the UK is a net pulse exporter, with per capita consumption below the global average.

Over the past several years, however, a comeback has been in the works.

The principal food crops grown in the UK are wheat, barley and canola. Pulses are grown as well, but on a much smaller scale. In a typical year, the country’s pulse output consists of 500,000 MT of fava beans and 100,000 MT of peas, including green peas (50% of the crop), marrowfat peas (40%) and yellow as well as other varieties of peas (10%).

The UK’s wet and cool climate is favorable to these particular pulse crops, allowing UK growers to reap very generous yields. Typical fava bean yields are 3.5 – 4 MT/ha. Typical pea yields are 3 – 3.5 MT/ha. Fava beans are grown both as winter and spring crops. The winter crop is planted in late October and November, and harvested from late July through August. The spring crop is planted in February and early March, and harvested from late August through early September. Peas are planted in March and April, and harvested from late July through August.

UK fava beans for food are almost entirely exported to Egypt, Sudan and the Middle East, with a good amount (100 – 250,000 MT) destined for Egypt, the world’s top fava bean market (annual consumption of 500,000 MT). The rest of the crop is used domestically for feed and aquaculture or exported in bulk vessels.

The pea crop is generally split evenly between the domestic and export markets. UK pea exports are destined mainly to Asian markets, where they are used to make snack products. At home, they are mostly consumed as mushy peas, a side dish that accompanies the English traditional dish of fish and chips, a favorite at seaside resorts.

Additionally, the UK imports a number of pulse products that cannot be grown domestically because of the island nation’s cool and wet climate. These include chickpea and lentils, and several varieties of beans. Peabeans are the bean of choice in the UK. About 100,000 MT are imported annually for canning and sold as baked beans in tomato sauce.

“The UK is a multicultural place and it used to be that, aside from peabeans, importing pulses into the UK was predominantly to serve customers whose traditional diets include pulses,” says Dan Holben, managing director at AGT Poortman and a member of Pulses UK, the national pulse industry’s association. “These days, nearly everyone eats pulses in some way.”

The UK’s pulse renaissance started in the grassroots. With such movements, it is tricky to pinpoint one origin story, but what occurred in Norwich undoubtedly had an impact.

In that particular city, a community of civically minded residents banded together to form the Transition Norwich Group, part of the Transition Network movement that empowers communities to take action on social issues. The group in Norwich was interested in finding ways to limit the impact of their diets on climate change. To that end, a team of researchers set out to identify foods that could be produced sustainably.

“Our interest in pulses came out of this realization that they were hugely beneficial for the environment,” says Nick Saltmarsh, who was then one of the researchers. “As we looked further into it, we came to appreciate the wider benefits of health and nutrition that go along with that.”

The team discovered that fava beans were widely grown in the area, but that the locals were largely unfamiliar with them because they were being produced for export. In order to see if the people of Norwich would be receptive to the beans, Saltmarsh and his colleagues decided to spearhead an experiment. They called it the Great British Beans Project.

“We bought a half ton of fava beans from a local processor,” recalls Saltmarsh. “They asked what we intended to do with them, and when we said we were going to give them to people to eat, they thought that was a ludicrous idea. They didn’t think people in Britain would want to eat them.”

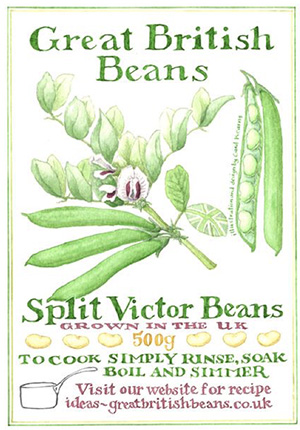

Saltmarsh and his friends packed the fava beans in a thousand 500-gram packets and distributed them through shops and local food fairs. Each packet came with a postcard that explained the project and directed people to a website for cooking tips and recipe ideas. On the reverse side of the card, people were encouraged to fill in and mail back a brief survey about the beans.

“Most of the pulses we eat in the UK are imported, so one of the things we asked was if people valued the fact that the beans were grown at home. That definitely appealed to people,” says Saltmarsh.

The feedback to the Great British Beans Project was overwhelmingly positive and led Saltmarsh and his colleagues to set up a company to sell fava beans locally. The company, Hodmedod’s, soon expanded its range to include other UK-grown pulses, including the marrowfat pea and other pea varieties, such as the Carlin pea. Last year, after several trials, the company produced its first lentil and chickpea crops. It harvested 50 MT of lentils and 15 MT of chickpeas.

“We started very small,” recounts Saltmarsh. “In the first couple of years, we were selling a few tons of each product a year. Over the eight years that we have been operating, we increased that to 20 to 100 MT, depending on the product.”

The Hodmedod experience demonstrated the UK’s appetite for pulses was there and growing. But little did Saltmarsh and his partners imagine that two global events were about to accelerate the trend beyond their wildest expectations.

Great British Beans Project postcard.

The International Year of Pulses

With consumer trends driving the shift to plant-based diets, the Global Pulse Confederation saw a golden opportunity to boost world pulse production and consumption. To this end, it reached out to its allies at the United Nation’s Food and Agriculture Organization and rallied industry members behind a successful effort to have 2016 declared the International Year of Pulses (IYP).

Franek Smith, a pulse trader with ADM Agriculture, was then president of Pulses UK.

“We decided to target pulse production in the UK and consumption in Europe overall,” he says. “We tried to get the government involved, but because of the pulse sector’s relatively small size, we have a small voice and our entreaties fell on deaf ears.”

When it became clear the private sector would have to shoulder the effort, Pulses UK members stepped up and agreed to a voluntary levy. The monies raised funded an advertising and promotional campaign that raised the overall awareness of pulses as an affordable, sustainable, healthy and nutritious food.

Among the more memorable elements of the campaign, Smith cites an invitation to the House of Parliament for the UK launch of IYP, which he attended dressed as a giant green pea.

“We met a number of members of parliament, as well as other important people and lords, and also George Eustice, who was the Minister of Agriculture at the time,” recalls Smith. The event gave the pulse industry a platform to present the health benefits of pulses to a distinguished audience of policymakers.

Other Pulse UK IYP events included a launch party at the London vegetarian restaurant The Gate that was attended by the press and social media influencers, several school events that allowed the industry to reach more than 20,000 children, and a Falafel Festival that attracted at least 1,000 people.

Official statistics on pulse consumption are unavailable, but based on anecdotal evidence, Smith believes canned pulse consumption alone is up 20% since IYP.

IYP success stories like that of the UK led the United Nations to declare February 10th World Pulses Day, providing the industry with a permanent, annual platform to tout the virtues of pulses.

The UK’s Falafel Festival similarly morphed into a yearly event, becoming an annual Dal Festival, a week-long celebration of dal and other pulse dishes from around the world. The festival has featured cooking sessions, appearances by celebrity chefs, shared meals, and a Dal Trail comprised of participating restaurants that serve up their own special pulse dishes for the occasion. Last year, 53 restaurants throughout the country participated in the Dal Trail and 20 Dal Festival events were held in nine cities, generating tens of thousands of impressions on social media and ample coverage in more than a dozen press outlets.

“Through GPC initiatives like IYP in 2016 and now the annual UN World Pulses Day, there is much more awareness of pulses, the benefits of consuming them, and most importantly, interesting and tasty recipes that show consumers and food manufacturers the many exciting ways to cook with them,” says Holben.

Franek Smith, giant green pea on the right, with MP Kerry McCarthy (center), sponsor of Pulses UK’s invitation to Parliament, and Barry Reed, secretary, on the left.

The rapid spread of the coronavirus around the globe has brought much of the world to a standstill. In the UK, a national lockdown went into effect in March. For the pulse industry, however, business has actually picked up.

“When the coronavirus hit, we were very busy,” says Smith. “Both canned and dried pulses flew off the shelves as people stocked up their cupboards with foodstuffs that can keep for an extended period of time. And as the virus has gone on, people have become accustomed to the new style of life.”

Since March 1, sales of canned beans and pasta in the UK jumped by 120%. At AGT Poortman, Holben reports, “We have had to carefully manage our supply chain to ensure that our products sourced in other nations affected by COVID-19 can be imported safely and that we are able to keep up with consumer demand and continuity of supply.”

The uptick in retail demand has been offset somewhat by the dramatic downturn in the food service sector. Seaside resorts, takeaways and fish-and-chip shops, all of which typically serve up mushy peas, have been closed for months.

“I think overall, pulse consumption is up, but different sectors have been affected differently,” says Smith.

“Ultimately, with what’s going on globally at the moment, I think most of us feel fortunate to work in the food industry,” concludes Holben.

The consumer shift to plant-based eating has been accelerated by IYP and the COVID-19 pandemic. The question now is whether that momentum can be maintained.

In the UK, the issue of Brexit looms large over the national consciousness.

“To a large extent, everything hinges on it,” muses Smith. “Brexit will mark such a fundamental change in our government and our economy.”

The UK’s farm sector has been largely supportive of the nation’s departure from the European Union. As a EU member state, the UK is subject to agricultural policy out of Brussels. With Brexit, the sector will have an opportunity to devise its own payment structure.

In this respect, the pulse industry is proposing a farm subsidy system based on a carbon footprint analysis. It is an approach that would encourage the seeding of pulses, since pulse crops require less water than other crops and enrich the soil through nitrogen fixation, thus reducing the need for chemical fertilizers.

Meanwhile, the food industry continues to launch more and more innovative products made with pulse ingredients.

“We have seen increased consumer demand for these types of products,” says Smith. “The amount of these items in supermarkets increases on practically a weekly basis.”

AGT Foods, a pioneer in the inclusion of pulse ingredients in everyday foods, recently made headlines with a $11.3 million joint project with ulivit to create a number of new plant-based products from pea, lentil and fava bean protein concentrates. In the UK, AGT Poortman partners with a large number of food manufacturers in Europe, the Middle East and Africa to find solutions to meet the growing customer demand for allergen-free plant proteins.

“We’re really excited about the work we’re doing together with our clients,” says Holben. “Pulses tick so many boxes for savvy consumers: they are a sustainable and nutritious protein source that will define the global food chain for the foreseeable future.”

UK / green peas / marrowfat peas / yellow peas / fava beans / International Year of Pulses / COVID-19 / Dan Holben / Nick Saltmarsh / Franek Smith / Kerry McCarthy

Disclaimer: The opinions or views expressed in this publication are those of the authors or quoted persons. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Global Pulse Confederation or its members.