September 17, 2020

With India’s withdrawal from the market, the region curbs its pulse output.

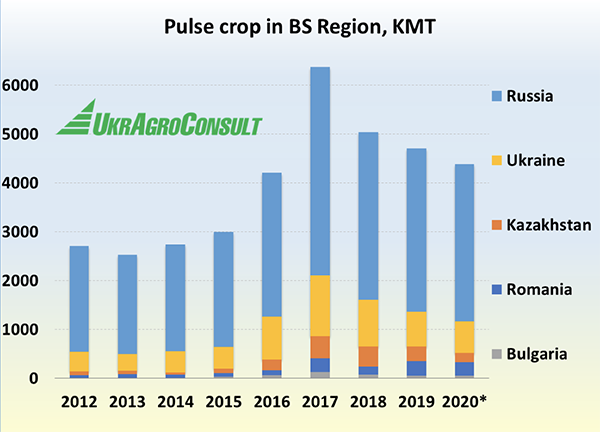

A few years ago, the countries of Russia, Ukraine and Kazakhstan suddenly emerged as important providers of pulse crops. Pulse production in the region started to trend upward in 2014 and exploded in 2017. Since then, however, it has been trending downward, largely because India, the biggest buyer of pulses from the region, has withdrawn from the market.

This was a recurring theme in the GPC Ask the Experts webinars. It was apparent during the Global Pea Outlook webinar when analyst Marlene Boersch of Mercantile Consulting Ventures projected Russia’s 2020/21 pea exports to fall from 590,000 MT the previous cycle to 575,000 MT this cycle, and Antonina Sklyarenko of the Pulse Producers and Customers of Ukraine forecast decreased pea production this year. And it was evident in the red lentil webinar as well when Kintal Islamov of JSC Atamaken-Agro anticipated a decrease in the area Kazakhstan growers seeded to lentils in 2020; in the absence of the Indian market, wheat, he said, had become a more profitable option.

With the region’s pulse harvests concluded or nearly concluded, the GPC checked in with experts from each of the region’s three major pulse producing countries to see how the crop turned out and to get their sense of the market outlook for Black Sea pulses in 2020/21.

Source: UkrAgroConsult

Yellow peas are the major pulse crop grown in Russia, with average annual production in excess of 2 million MT. The country also produces significant amounts of chickpeas (almost entirely small-sized kabuli) and lentils (both red and green in roughly a 60/40 proportion), as well as lesser amounts of lupins and beans.

Russia’s peas and lentils are typically seeded in March and April, with chickpeas seeded from April to mid-May. This year, the crop was seeded within the regular window and harvested during the normal timeframe as well. The yellow pea and lentil harvest concluded in mid-May and the chickpea harvest is expected to wrap up by late September in the northern growing regions.

Yellow Peas

Four years ago, Russia harvested a bumper yellow pea crop of 3.3 million MT, but since then annual production settled in the 2.3-2.5 million MT range. This year, high prices attracted grower interest and resulted in a 10% increase in the seeded area. But dry conditions in parts of the growing area resulted in lower yields and consequently a reduction in production. Cem Bogusoglu of GP Global Group estimates Russia’s 2020 yellow pea crop at 2.2-2.3 million MT, down slightly from last year. The quality of the crop, he reports, is excellent.

India had been Russia’s primary export market, but because of an increase in the import tariff, it has had to find other destinations for its yellow peas.

“Four years back, Russia exported 1.2-1.3 million MT of lentils,” says Bogusoglu. “But with this year’s smaller crop, I expect exports for 2020/21 to be around 750-800,000 MT. The export amount is difficult to quantify because local consumption may change.”

In 2014, Russia banned the import of meat from the European Union as part of escalating sanctions that spun off as a result of Russia’s annexation of Crimea. Since then, local meat production has increased, driving up domestic demand for yellow peas as feed.

The biggest export markets for Russian yellow peas are the feed markets of Italy and Spain. In 2019/20, these two markets took 300-350,000 MT of Russia’s 800-850,000 MT of yellow pea exports. Other destinations include Türkiye and neighboring markets (200-250,000 MT went there in 2019/20), and Pakistan, Bangladesh and other markets in the Indian subcontinent (accounting for 200-250,000 MT of 2019/20 exports).

As of this writing, yellow peas are trading at $255-260 C&F Karachi.

“I don’t expect large price fluctuations as there is strong bottom price support from the feed market,” says Bogusoglu. “These are the lowest prices we have seen on yellow peas and I expect them to remain in the $260-280 range depending on availability at origin and destination ports.”

Chickpeas

Russia’s chickpea production is almost entirely of the kabuli type and consists mainly of small caliber sizes (6-7mm). Here again the primary export market for Russian chickpeas has been India, which uses them mainly as a substitute for desi chickpeas. Other destinations include Pakistan and the Middle East, with some Russian chickpeas entering European markets via Türkiye.

Like other chickpea origins, Russia enters the 2020/21 campaign with a significant carry-in. Bogusoglu estimates 80,000 MT of old crop inventories still remain, most of which dates back to the 2018/19 campaign, when India imposed an import duty.

The drop in prices due to the market glut dampened grower interest. Bogusoglu estimates the area seeded to chickpeas at 154,000 ha., a 30-40% reduction from last year. The weather, he reports, has been favorable so far and, barring rains at harvest, he projects production at 185,000 MT. Including carry-in, that would bring Russia’s total chickpea supply to 265,000 MT.

Of that amount, Bogusoglu expects 215,000 MT to be exported over the course of the 2020/21 campaign and 40,000 MT to be consumed domestically, leaving a negligible carryout of 10-15,000 MT.

At the moment, with prices presently low, growers are holding onto their chickpeas in the expectation that prices will improve in early 2021.

“Chickpea prices have been trending up in the past two weeks and should continue to do so,” says Bogusoglu. “Of course, there is a limit to the upside, since there is a large desi chickpea crop coming from Australia and India has sufficient stocks to last through their next harvest.”

Currently, Russian chickpeas are trading into India in containers at $460-480 per MT.

Lentils

Russia’s lentil production ramped up only recently, growing from 20-30,000 MT a few years ago to an estimated 100–120,000 MT today, according to Bogusoglu.

“Lentil production is up on good prices and also thanks to improved agricultural technology and greater farmer experience,” he says. “Like they did with peas and chickpeas, Russian farmers are getting better at growing lentils. I remember when I began my career in 2003, Russia’s chickpea production was no more than 10,000 MT. In 15 years, it has increased thirty-fold. We are seeing that kind of growth now with lentils.”

The top markets for Russian lentils are Türkiye, Egypt and the Indian subcontinent. Based on the samples he has seen, Bogusoglu describes the quality of Russia’s 2020 lentils as excellent. Russia’s proximity to destination markets gives it an advantage over Canada, but it has yet to establish a phytosanitary agreement with India.

Presently, bids for Russian lentils are in the $480-490. Production out of Canada and Australia will determine in which direction markets go from there, says Bogusoglu.

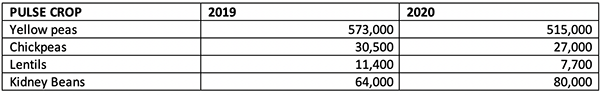

As in Russia, yellow peas are the main pulse crop grown in Ukraine. The country also produces lesser amounts of chickpeas and lentils.

Sergey Feofilov of UkrAgroConsult describes the weather during the pulse growing season as a seesaw, with dry conditions predominating in March and April, much needed rains arriving in May, and drought setting in again in June. The pattern continued in July, with rains improving soil moisture profiles, only to have dry conditions return once more in August.

Yellow Peas

Ukraine’s yellow pea crop is usually planted in early April, but a warm winter this year saw growers get an early start, with the first yellow peas seeded in mid-March. Sergey Feofilov of UkrAgroConsult estimates 240,000 ha. were seeded to yellow peas this year, a 7% decrease from last year and 21% less than the five-year average. The drop in the seeded area, he says, is explained by low profitability and depressed export demand.

“Ukraine’s farmers are very sensitive to export demand,” explains Feofilov. “Their planting decisions are very much influenced by what crop is in demand in foreign markets.”

In 2019/20, Ukraine’s yellow pea exports declined by 36% compared to the previous campaign, largely because of India’s withdrawal from the market and also because of reduced availability. In April, yellow pea exports were up 61% compared to March as the COVID-19 pandemic led to a spike in export demand through May. Domestic demand also increased because of the pandemic, but not as drastically.

More than 40% of the exports went to Europe in 2019/20, with India taking just 13%. Other destinations included Türkiye (8%) and Uganda (7%), with smaller volumes shipped to Malaysia, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

The yellow pea harvest typically wraps up by mid-August. This year, despite the early start to seeding, the harvest concluded only slightly ahead of normal, as cool temperatures during the growing season slowed crop development.

Feofilov estimates Ukraine’s 2020 yellow pea crop at 515,000 MT off of yields of 2.1 MT/ha. and indicates 115,000 MT of new crop has already been exported. Given Ukraine’s reduced supply and India’s exclusion of yellow peas from its 2020/21 import quota for peas, he foresees exports continuing to decline this campaign.

Ukraine yellow pea FOB prices are currently in the $220-230 range.

Chickpeas, Lentils and Kidney Beans

This year, slightly more than 21,000 ha. were seeded to chickpeas and lentils combined, while the kidney bean area expanded by 15% to 48,000 ha.

In 2019/20, chickpea exports increased by 87% over the previous campaign to 12,000 MT. Pakistan is the biggest market for Ukrainian chickpeas. In 2019/20, it accounted for 47% of exports. Other destinations included Egypt (13%), Jordan (8%), Germany (5%) and Israel (5%).

Lentil exports, meanwhile, fell off by 5% in 2019/20. The major markets for Ukrainian lentils are Türkiye (which took 45% of 2019/20 exports) and the EU (which took 29%).

As with yellow peas, the COVID-19 pandemic led to a spike in export demand and domestic consumption for Ukraine’s chickpeas, lentils and kidney beans during the months of April and May. Lentil exports, for instance, saw a 200% increase. Consequently, as with yellow peas, carryout volumes for these pulses is down considerably.

For 2020/21, Feofilov projects chickpea exports will decrease to 10,000 MT on reduced supplies. He forecasts kidney bean exports at 40,000 MT.

Presently, Ukraine’s chickpeas are trading at $390 CFR and green lentils (6 mm) at $580 CFR. Red lentils are no longer available and were trading at $550 CFR.

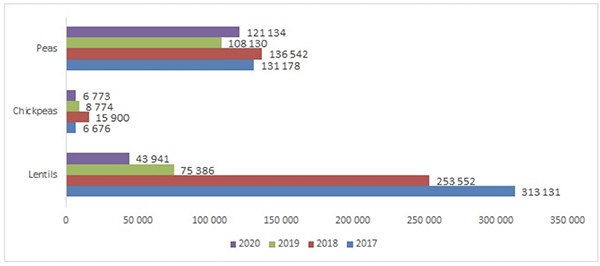

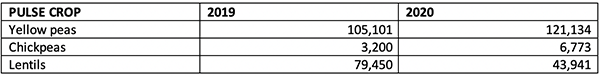

In 2017, Kazakhstan’s lentil production exploded, more than doubling year-on-year to 313,000 MT. With domestic pulse consumption at a minimum, most of that volume made a splash in the lentil export scene, sending ripple effects that caught the attention of Canada, the world’s leading lentil exporting nation. Since then, Kazakhstan’s lentil production has been on the global pulse industry’s radar. Just last year, the Western Producer ran a headline proclaiming Kazakhstan the Saskatchewan of Asia (Saskatchewan being Canada’s top lentil-producing province).

But since that peak in 2017, Kazakhstan’s lentil output has been falling off fast. In fact, Kintal Islamov of JSC Atameken-Agro notes that production has been trending downward for all pulses.

Source: JSC Atameken-Agro.

“Pulses are not as profitable for farmers here compared to alternatives such as flax or wheat,” he explains.

This year, lentils, peas and chickpeas were seeded on 182,152 ha., a 17% decrease from last year and a far cry from the 451,800 ha. seeded in 2017. In the case of lentils alone, plantings fell by 46% on the year to 49,900 ha.

Kazakhstan’s 2020 pulse crops were planted and harvested in a timely fashion. The peas were planted first in late April, followed by the lentils in mid-May and the chickpeas during the second half of May. The harvest started in late July, with the peas and lentils first, and concluded in early September with the last of the chickpea crop coming off the fields.

“The summer was rather dry this year,” reports Islamov. “We didn’t get a lot of precipitation during the vegetative period. The quality should be quite good, but yields will be down. It is a bit early to talk volume, but we will have a smaller crop than last year for sure because of the weather conditions and the reduction in the seeded area.”

In 2019/20, Türkiye was the major destination for Kazakh lentils, accounting for 93% of the export volume. Kazakhstan’s chickpea exports went Iran (42%) and Türkiye (37%). The biggest buyers for its dry peas were Afghanistan (43%) and Uzbekistan (34%). Other destinations for Kazakh dry peas in 2019/20 included Egypt (8,500 MT) and Spain (3,300 MT).

With harvest complete, Islamov says there is active demand for Kazakh lentils from the domestic and Central Asian markets.

Current prices offered on EXW terms stand at $450 for lentils and $170 for peas, both below Islamov’s liking.

Black Sea Region / Russia / Ukraine / Kazakhstan / Cem Bogusoglu / Sergey Feofilov / Kintal Islamov

Disclaimer: The opinions or views expressed in this publication are those of the authors or quoted persons. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Global Pulse Confederation or its members.