March 30, 2023

AgPulse Analytica’s Gaurav Jain looks at the details in India’s massive increase in export numbers for chickpeas, peas and lentils and what this means for the future of the market.

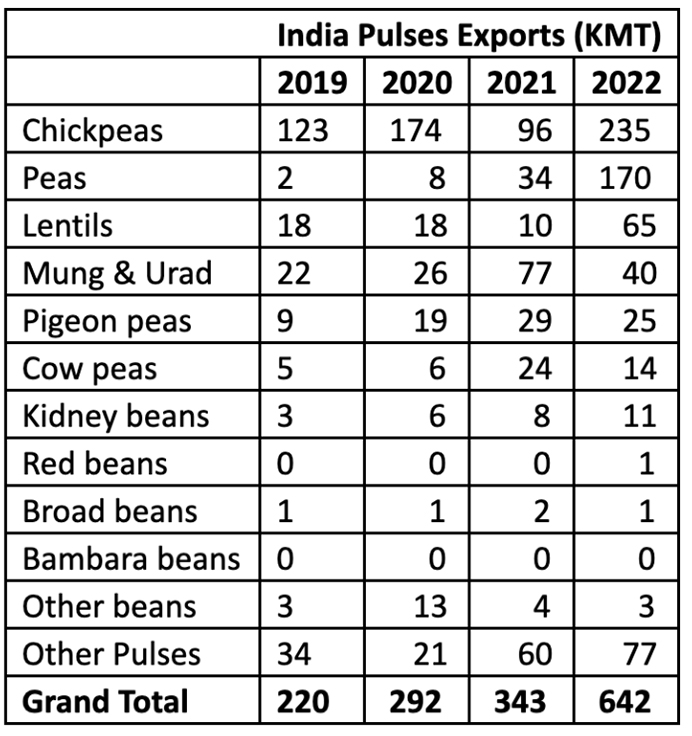

According to official statistics, India exported a total of 642 KMT of pulses in 2022, the highest volume in at least this millennium, gaining a significant amount of attention from the press and the pulse community. The increase came largely from chickpeas, peas and lentils, while other pulses, such as mung beans, pigeon peas and cow peas, saw a decrease in export volumes.

Big jumps were noted in chickpeas (+145% YoY), dry peas (+406% YoY) and lentils (+565% YoY).

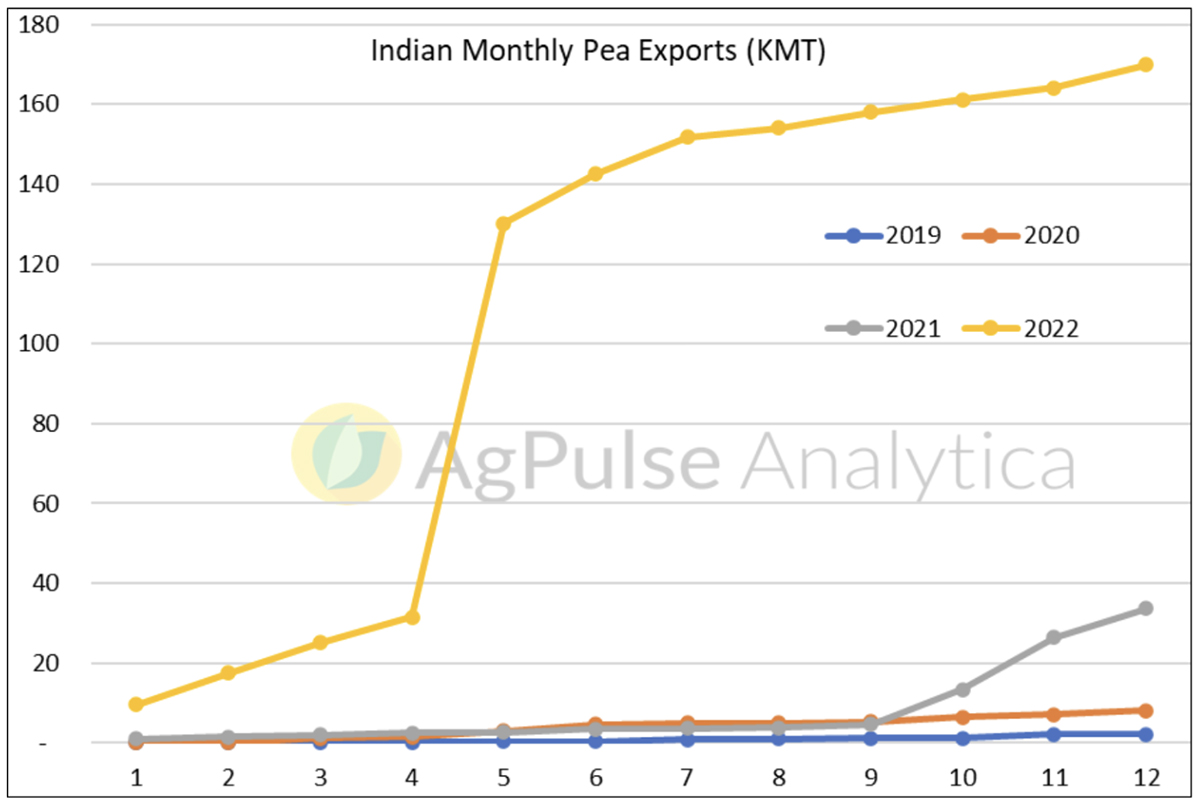

Not long ago, India was the world’s largest importer of peas. Constant policy changes in recent years, however, have reduced pea imports to negligible quantities.

These fluctuating policy changes resulted in huge pea stocks in port silos, with trade sources putting this figure at around 250,000 metric tonnes.

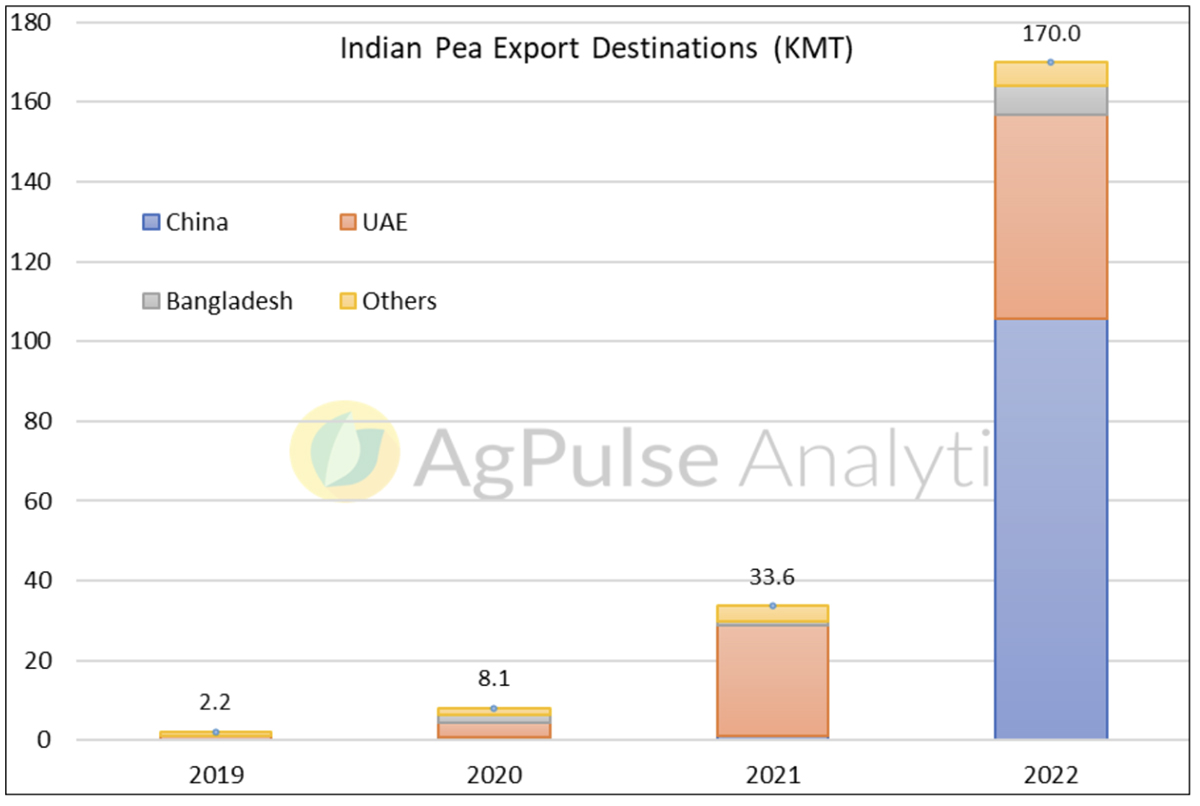

In Q4 of 2021, India started exporting these peas stored at ports with volumes reaching peak in May 2022 when two bulkers loaded with the port stocks were shipped to China. China, however, reported Canada as the origin of these peas in its monthly statistics report.

Other destinations were served by containers and road transport, which restricted the majority of movement to neighboring countries. The largest export destination after China is the United Arab Emirates, to which 51,363 MT of the port stock peas were destined. The third-largest export destination was Bangladesh with 7,178 MT, and the rest of the world made up 5,896 MT.

The flow of re-exports from the port stocks continues, with between 3 and 6 KMT shipped every month. It is likely that this these stocks will run out very soon after which India’s small domestic crop and massive domestic consumption will prohibit further exports.

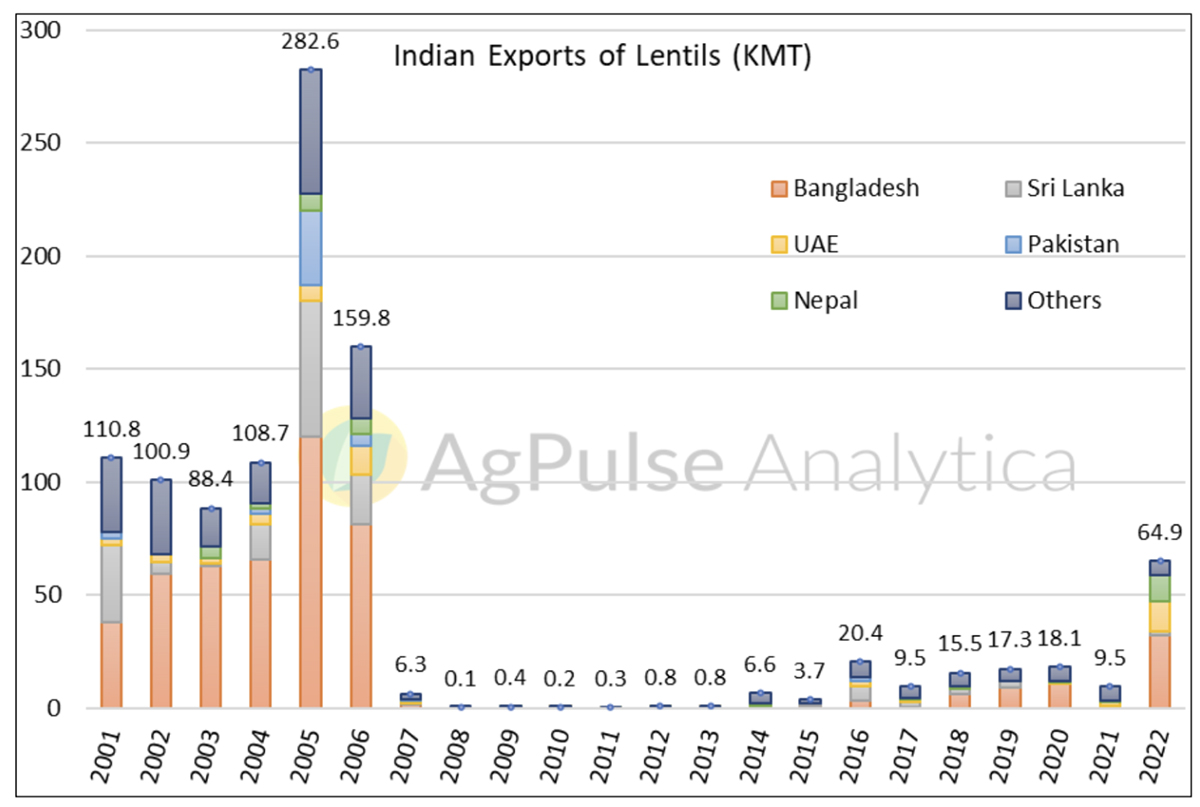

Until 2006, India was a sizable lentil exporter with the bulk of shipments destined for its South Asian neighbours. A record 282,572 MT of lentils were exported in 2005 after which the figure dropped to just 55 MT in 2008 and remained below the 1000 MT mark until 2013.

Despite poor production in 2022, Indian lentil exports have seen a revival in the past year, surging by 565% (YoY) to 64,891 MT. Out of these, 32,063 MT went to Bangladesh, 13,404 MT to the UAE and 11,751 MT to Nepal.

Higher than usual opening inventories made the export volumes possible, with traders taking advantage of price parity. Payment issues at some destination countries likely contributed to the increase of Indian lentil exports last year.

At AgPulse, we expect record numbers for the 2023 lentil crop, which is currently being harvested. Compared to last year’s 1.27 MMT, production should reach 1.65 MMT and Indian domestic supplies will be replenished. Australia and Canada, who typically export to India, also have larger crops, boosting global supplies. India’s export potential in 2023 will depend upon the competitiveness of lentils in other South Asian countries, and we expect the flow to continue to remain above the five-years average.

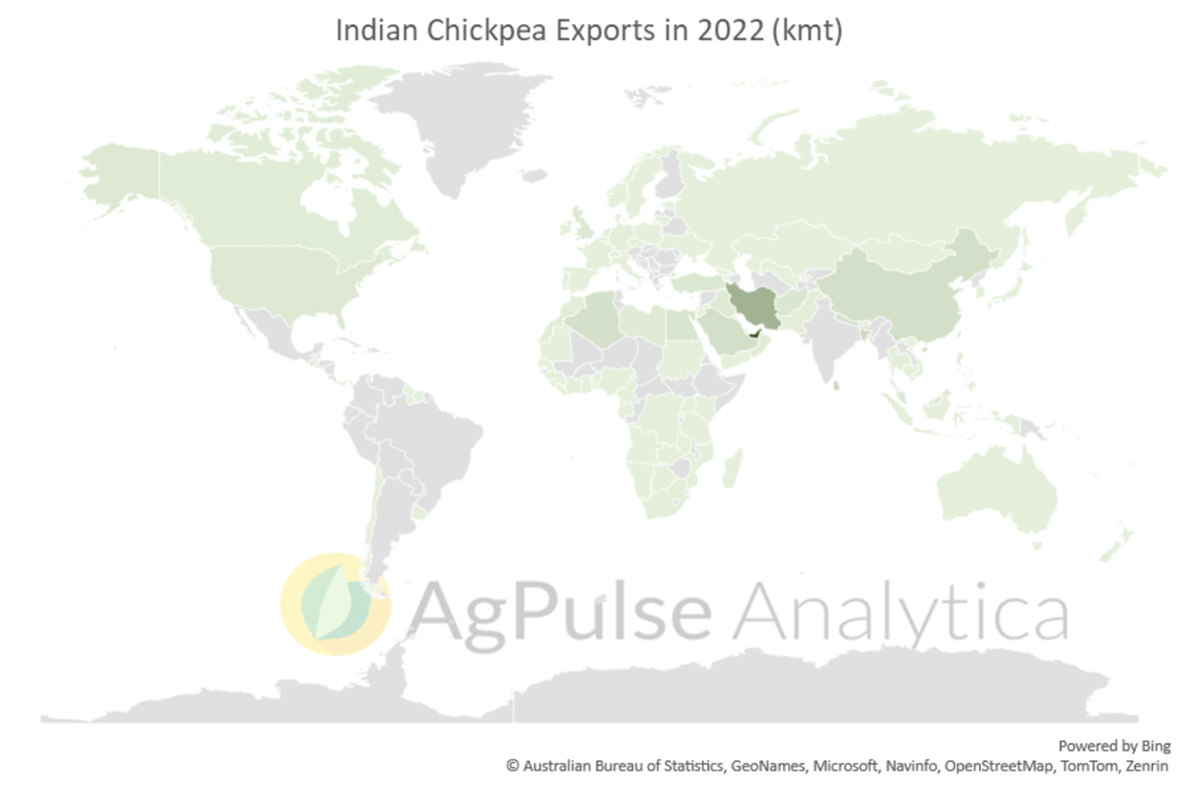

For kabuli chickpeas, India is unique in being both a key importer and exporter. Imports usually tend towards small and mid-calibre kabulis while larger calibres are exported. Along with Mexico, India is one of the two biggest exporters of large calibre kabulis in the world. Demand is diverse and exports reach a range of nations across Asia and Africa.

When it comes to desi chickpeas, India is the global leader in both production and consumption. Since the former is not sufficient to satisfy the latter, India imports from East Africa, Myanmar and Australia.

In the past year, domestic kabuli supplies were tight but for elevated global prices meant India managed to increase exports year on year. For the first time in a while, India exported desi chickpeas last year, with destinations centring on Iran, Bangladesh and Nepal. This was due to domestic prices falling low enough to compete with traditional exporters in South Asian destinations.

The current crop, which is under harvest, has the potential to be one of the best for kabulis and average for desis. The possibility of higher availability means India is poised to remain an exporter of chickpeas well into 2023.

It is unwise to consider the 2022 export volumes as a new normal. The increase was due to multiple factors, such as low global availability, ongoing demand recovery from the easing of COVID-19 restrictions, payment issues at many destination countries and the clearing of port stocks.

To summarize our projections for Indian pulses exports this year, we can expect:

Disclaimer: The opinions or views expressed in this publication are those of the authors or quoted persons. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Global Pulse Confederation or its members.