June 22, 2021

Persistent drought in the U.S. Northern Plains and Canadian Prairies has growers hoping for rain.

Photo courtesy of Saskatchewan Pulse Growers.

With summer seeding wrapped up in Canada and the U.S., growers in the major pulse producing areas are holding out hope for rain. Conditions have been especially dry in the U.S. Northern Plains and the Canadian Prairies, where most of North America’s pulse production is concentrated. According to reporting in AgWeek, some in the U.S. state of North Dakota are even comparing this year’s conditions to the historic drought of 1988, the worst in the past century.

In Canada, Carl Potts, executive director of Saskatchewan Pulse Growers, tells the GPC that the roots of the drought, so to speak, extend back to the dry finish of the 2020 growing season.

“The crops from last year utilized a lot of the subsoil moisture that was there at the time,” he explains. “Then throughout the winter, we didn’t get a lot of precipitation and the land was quite dry heading into planting time. We got very little rain in April and May, when the crop was seeded.”

The third week of May did bring rainfall across the province and helped avoid an early end for many pulse crops. Farhan Adam of Marina Commodities, a pulse trading company based in Ontario, says a few growers told him that it wasn’t for that moisture, “they would have called their crop insurance. It was that bad.”

Across the border in the U.S., the story is much the same. Brian Gion, the marketing director for the Northern Pulse Growers Association, indicates 75% of North Dakota is experiencing extreme drought. In neighboring Montana, another major pulse growing state, Gion says there are about 18 counties that are also under extreme drought.

“It gets better the further west you go, but you have to go as far as Great Falls to find a decent amount of moisture,” he says.

Great Falls lies 780 km to the west of Montana’s border with North Dakota. From there to the Palouse region that straddles the states of Idaho and Washington, conditions are better. Phil Hinrichs, the director of sales and procurement at Hinrichs Trading division of Ardent Mills, indicates that although conditions were dry at the start of planting, they have since improved in western Montana and the Palouse.

Below, we take a closer look at the seeding of North America’s 2021 pea, lentil and chickpea crops.

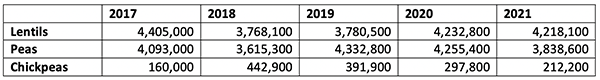

The latest StatsCan figures indicate that Canadian growers seeded 4,218,100 acres to lentils this year, a slight drop from last year’s 4,232,800 acres; red lentils account for about 70% of the area. The area seeded to peas and chickpeas, on the other hand, are down considerably at nearly 10% for peas and 29% for chickpeas.

The reduction in the pulse area is attributable to high prices for competing crops. Even though pulse prices were up significantly on the year, they were not as attractive to growers as those of canola, barley and other crops.

“It was a tough decision for farmers this year,” says Adam at Marina Commodities. “Canola and wheat were at all time highs, but some pulses were also pretty strong, so there was a bit of an acreage shift, but not too much.”

In the case of peas, Adam indicates, most of the reduction is in green peas. Of the 3.8 million pea acres reported by StatsCan, green peas account for no more than 500,000 acres, a 38% drop from a year ago.

“This is an effect of pricing,” says Adam. “Green pea prices have been subdued due to oversupply.”

“When you look at peas,” adds Potts of Saskatchewan Pulse Growers, “high yellow pea prices combined with a lack of a premium for green peas would suggest an increase in yellows and a decline in greens.”

The bulk of Canada’s pulse production is concentrated in Saskatchewan, which grows 90% of the nation’s lentils and chickpeas, and 50% of its peas and faba beans.

Potts reports that, because of the dry conditions, growers started seeding their pulse crops in late April, a bit earlier than usual. Without much rainfall to interrupt fieldwork, they progressed quickly and wrapped up ahead of schedule in late May. The province received good rains in the third week of May, which helped establish the crop and gave it an early push. Frost hit Saskatchewan in late May, but pulse crops had not yet emerged and were likely unaffected.

“Moving forward, we don’t have large amounts of reserves in the soil and we are going to need very good and timely rains throughout the growing season to produce even average yields,” says Potts. “The other concern is that we have had some very warm weather already. As we head into the heart of the growing season, high temperatures can negatively impact flowering and also reduce yield potential.”

Because of these factors, production projections on lentils, for instance, were down from last year’s 2.9 million MT to 2.5 million MT despite similar acreage, indicates Adam. But the precipitation in late May has given him renewed optimism that average yields may be possible.

“Those rains have really changed the production outlook,” he says.

Adam also sees a positive market outlook for lentils in 2021-22. India’s recent decision to allow the free import of black matpe, pigeon peas and mung beans signals to Adam that pulse supplies are low there and India will soon incentivize the import of other pulses as well.

“India’s next lentil crop won’t be harvested until March of next year. Until then, India does not have enough lentils. Sooner or later, they will have to import. It will make sense for them to lower duties when local prices get a bit higher in order to constrain food inflation,” he says.

There is a chance India may enter the market for yellow peas as well, but Adam strikes a more cautious tone there: “There has been talk that India will open a quota for yellow pea imports. If that happens, the yellow pea market will become very strong. But India is a wildcard.”

In the absence of activity from India, Canadian exporters found a new market for yellow peas in China. Presently, China has ample supplies, Adam indicates, but it is certain to remain a major buyer moving forward.

Over the past couple of weeks, there has been some price correction, says Adam, as buyers are holding off on making new purchases in the hope that prices will cool further. However, he does not see that happening.

“We will be going in with negligible carryover on pulses and demand from all destinations -- Türkiye, India, Pakistan, Dubai, Sri Lanka – continues to be there. Buyers have hardly bought any new crop yet. Farmers are holding onto their new crops until they see crops doing well as the harvest is still a few months away. They know the buyers have bought poorly and they will come. That is why we see markets remaining strong even during the harvest.”

Further, he points out that logistical headaches due to container shortages continue to be a major factor affecting shipments, creating shortages at markets where cargoes are not arriving on schedule.

“Eventually, this pent-up demand will come and the market will remain firm moving forward,” says Adam.

Meanwhile, domestic demand continues to trend upward, with new players in the plant-based ingredients space ramping up operations. Roquette and Merit Functional Foods are just two of the companies that have plants coming online in the western prairies.

“I understand Roquette will be ramping up purchases this fall,” says Potts. “These plants aren’t fully operational yet, but its going to draw in a significant amount of domestic pea production. We are starting to see it and we are hoping to have more processing capacity here in Canada so that we are a little more diversified between domestic and our traditional export demand.”

Source: StatsCan.

The latest USDA numbers indicate U.S. growers seeded 611,000 acres to lentils, 893,000 acres to peas and 290,000 acres to chickpeas this year. Compared to last year, that represents an increase of nearly 16% for lentils and 7% for chickpeas, and a decrease of just shy of 11% for peas.

“High prices for the major commodities were a major factor in planting decisions,” says Gion of the Northern Pulse Growers. “Some growers always plant pulses for the agronomic benefits, but when you have high soybean prices and also good insurance on soybeans, like there is this year, it makes it more favorable to plant soybeans over peas and other pulses.”

He reports that producers in North Dakota and Montana seeded more lentils this year on strong prices; he estimates 75% of the overall acres were seeded to green lentils and 25% to reds. The increase in the chickpea area came mostly from growers in Idaho; in Montana and North Dakota, says Gion, chickpea plantings were actually down from last year. Speaking to the increase in the Pacific Northwest, Hinrichs of Hinrichs Trading division of Ardent Mills relates that strong competition from canola and wheat required his company to raise its contract prices; in the end, however, he is satisfied with the support received from growers.

“It was a pretty bearish market for chickpeas going into February and March,” says Hinrichs,” so 290,000 acres is a good number considering.”

The U.S. produces both small caliber (6-7 mm) and large caliber (9-10 mm) kabuli chickpeas, and a very small number of desi chickpeas. By Hinrichs estimation, 80% of the chickpeas seeded this year are of the large caliber kabuli type.

As for peas, this marks the second consecutive year that there has been a reduction in the seeded area; Gion attributes the decrease to strong soybean prices.

“More yellows than greens were seeded this year because companies like AGT Foods and ADM use yellow peas for protein,” adds Gion. He estimates 70% of the pea area was seeded to yellow peas this year.

In the Northern Plains, the crops were planted in dry conditions with minimal subsoil moisture. Because of the arid conditions, some growers held off the start of seeding in the hopes of rain, but not much came and planting progressed quickly, wrapping up by May 20, the federal crop insurance cutoff.

“We’ve had some rain here and there, but then in early June we had temperatures above 100 degrees F and winds, so any moisture that would have been there just evaporated,” says Gion. “In North Dakota, especially, growers need rain or they won’t have a crop.”

Adding to this season’s woes, there are concerns that a late May frost possibly damaged some pulse crops near the Canadian border.

In the Pacific Northwest, most of the seeding took place in the month of April under good conditions, according to Hinrichs. He indicates there hasn’t been much moisture but notes that June is the wet month for the region and typically brings sufficient precipitation. He anticipates normal chickpea yields this year (1,100 to 1,300 lbs/acre).

“The chickpea has the edge when it comes to its taproot,” points out Hinrichs. “It will be able to hold on longer and be able to start performing above and beyond a lentil or a pea. The jury is still out on how lentils and peas are going to hold on in this weather.”

That said, though, Hinrichs notes there hasn’t been much rain in the month following the emergence of the crop. The crop is developing nicely, he reports, but without moisture, the preemergence chemicals are not activating well and weeds are starting to be an issue.

“Rains are always welcome. But if we don’t see good rains, I think we will see yields falling off on everything from wheat to canola, and I think chickpeas will shine,” he says. “We are short on acres in the face of domestic and export need, so with average yields we are going to see a really bullish scenario shape up on chickpeas.”

The U.S. heads into MY 2021-22 with low carryover stocks across all pulses. Gion reports peas are all but sold out. Chickpea stocks are down on the year as the seeded area has been dropping and domestic usage has been increasing. Some growers, says Gion, are holding on to their chickpea inventories in the expectation that prices will improve. Hinrichs sees this as well and adds that growers are counting on renewed demand from restaurants and sporting venues as they reopen following the 14 months of business disruptions caused by COVID-19.

“The overall global view is that chickpeas are definitely in short supply once things get back to normalcy,” says Hinrichs. “We have a market for chickpeas in the U.S. that needs 400,000 acres planted every year. Exports can also flourish when the dollar isn’t as strong as it is right now.”

Gion adds: “With stocks being so low, if this drought continues, it will be interesting to see if our processors will be able to get their end users what they need at the price point they are willing to pay. That is always a concern when you’re buying something to pass down the supply chain to the end user. If the price is too high and they have the ability to change their formula and use something else instead of your product, they’ll just switch.”

Pulses have made considerable gains in the food sector as ingredients. Since 2016, Gion indicates there have been on average 1,100 new food products featuring pulse ingredients launched in the U.S. every year. Just six months ago, for instance, AGT Foods launched its Veggipasta line, made solely with yellow peas.

“COVID-19 pushed some usage up, too,” he continues. “It may retract a bit as the pandemic subsides, but people have found new ways of cooking and new affordable ingredients to get their protein from, so I don’t see it retreating to pre-pandemic levels.”

Additionally, as vaccination rates continue to climb, pent up demand from the HORECA sector will begin to return to levels last seen in the pre-COVID-19 days of Q1 of 2020.

“I look for an interesting year on the pulse side of things,” says Hinrichs. “I think we are going to see yields that are not quite as dramatic as what we have seen in the past. June is a big month for moisture, so we have to wait and see. If we don’t get rains in June, it is going to be a wild ride from October through March. There will be a shortage and a lot of demand for people to plant pulses in 2022.”

North America / USA / Canada / Carl Potts / Saskatchewan Pulse Growers / Brian Gion / Northern Pulse Growers Association / North Dakota / Montana / Palouse / Farhan Adam / Marina Commodities / India / China / USDA / Northern Plains / Pacific Northwest / Phil Hinrichs

Disclaimer: The opinions or views expressed in this publication are those of the authors or quoted persons. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Global Pulse Confederation or its members.