November 12, 2020

The fourth edition of the India Pulses and Grain Association’s webinar series examines the inner workings of India’s lentil market and the outlook for Canadian and Australian new crop lentils.

On Friday, 5 November, the India Pulses and Grains Association (IPGA) hosted the fourth Knowledge Series webinar. This time the focus was on lentils, a timely subject given India’s recent extension of its tariff reduction on lentils, as well as the start of rabi sowing season and new crop coming down the pipeline from Canada and Australia.

The webinar was moderated by Anurag Tulshan, managing director of Esarco and IPGA’s East Zone Convenor as well as the Global Pulse Confederation’s Vice President for South Asia. Tulshan welcomed attendees and stated that the previous three webinars in the series – the first on India’s recent agricultural reforms, the second on chickpea markets and the third on the outlook for kharif crops 2020 – averaged 800 attendees each from throughout the pulses value chain and the world. The lentil webinar, he said, was well on its way to matching that attendance.

Tulshan then introduced the panel:

Following these brief opening remarks, Tulshan handed the floor to the first panelist, Dr. Malhotra.

Dr. Malhotra began by noting how far India has come in terms of achieving pulse self-sufficiency. In 2015/16, India’s pulse production amounted to 16 million MT, well short of its requirement of 25 million MT. Today, its production is nearly enough to satisfy internal demand, though there are still occasional shortfalls in lentil and yellow pea production.

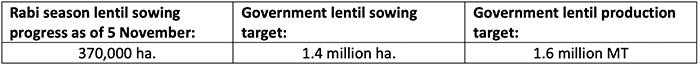

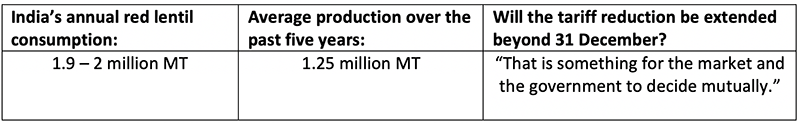

In India, lentils are a rabi season crop, grown during the Northern Hemisphere’s winter months. Seeding of the 2020/21 crop is currently underway and Dr. Malhotra reported that as of the time of the webinar, 370,000 hectares had been seeded to lentils, double the pace of the previous rabi season. He attributed the advanced pace of seeding to reservoirs being full thanks to the 9% excess rainfall that resulted from the monsoon’s late withdrawal. The government’s lentil sowing target this rabi season is 1.4 million hectares and the production target is 1.6 million MT. The normal planting window runs through December 15.

In closing, Dr. Malhotra noted that India has made significant strides in improving lentil genetics and developing higher-yielding and biofortified lentil varieties.

Sunil Kumar Singh, Additional Managing Director of NAFED, spoke next. He mentioned that the pulse crop with the greatest supply constraint in India today is the red lentil. He then touted India’s improvement in pulse production, procurement and supply management over the past five years, from the soaring prices of 2015 to a public distribution system that, in the face of a global pandemic, successfully distributed 1 kg of pulses to more than 1.95 million families for a nine month period, and has the ability to continue to do so. Therefore, despite some supply-demand imbalances, the availability of pulses in India is not an issue today, he stated.

But, he admitted, one of those imbalances is the red lentil supply-demand situation. NAFED’s red lentil inventories have run out and India’s overall supply is short. Consumption is estimated at 1.9 – 2 million MT, and production, as Dr. Malhotra had stated, is projected at 1.6 million MT, leaving a gap that will need to be met via imports.

In order to incentivize seeding, the government of India set a minimum support price of Rs. 5,100 and, in the case that market prices were to fall below that level, assured growers that the government would purchase every grain at that price. Consequently, Singh said that as long as the government keeps growers happy, the expectation is that in a year or two, India will be able to produce 2 million MT of red lentils and achieve self-sufficiency.

Over the past five years, India’s annual red lentil production has amounted to 1.25 million MT, meaning that the country has had a significant dependence on imports. Recently, the government reduced the import duty on lentils in order to incentivize imports and stabilize prices, and the influx of imports under the reduced tariff has already cooled the market.

Following his presentation, Tulshan asked Singh if there was a chance for the import duty reduction on lentils to be extended beyond 31 December. The reply: “That is something for the market and the government to decide mutually.”

Next, Rakesh Khemka, managing director of Uma Exports, shared his thoughts as an importer. Red lentils, he said, is one of India’s most imported pulses. Last year, 750,000 MT were imported into the country.

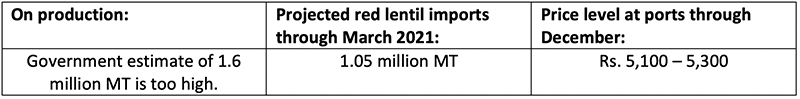

He then mentioned a discrepancy between the government’s and the industry’s estimated 2020 rabi production. The government had estimated 1.1 million MT, but the trade estimated around 750,000 MT. Because production levels factor heavily into policy decisions, the government and the industry should arrive at a consensus, he said, otherwise it is difficult to properly plan imports with such a sizeable gap. Khemka also said that the government’s free distribution of chana saw low-income red lentil consumers shift to that pulse instead.

This year, he believes red lentil production was down from last year, which is why the government reduced the duty from 30% to 10% and extended this decrease from the end of August through 31 December.

Importers, he emphasized, need long-term policies in order to plan imports. At the moment, traders are hesitant to buy lentils in November and December because they are afraid the consignments may arrive after 31 December and they will be required to pay the higher duty. It takes at least three months for Canadian cargo to arrive at an Indian port, he noted.

“Bi-monthly policies are not helping our traders,” he stated. “We are unable to plan our imports.”

He called on the government to refund traders who paid 30% duty during 1-17 September, between the time the original duty reduction lapsed and the new extension was announced, and to also provide the industry with an annual policy plan, or at least a six-month plan, to help them properly plan their imports.

At this point, NAFED’s Singh interjected that the government is aware of this concern and he said he expects the government will find a solution to this situation in the near future.

By Khemka’s estimation, India’s total red lentil imports through March 2021 will amount to 1.05 million MT. But much depends on government policy moving forward.

Tulshan then asked Khemka for his price outlook for the next four months, considering that NAFED stocks were empty, private inventories amounted to about 300,000 MT and there were possibly another 150,000 MT in the pipeline. Based on the average consumption estimate, Tulshan calculated monthly consumption of 150,000 MT.

Khemka responded that he expects port prices to remain in the Rs. 5,100 – 5,300 range through December. After the new year, unless the duty reduction is extended, he foresees prices rising again by as much as four rupees in the port areas. Post-harvest, if production does in fact come in at 1.6 million MT, Khemka anticipates prices of Rs. 5,000 – 5,100 in the port areas.

Rav Kapoor, CEO and director of ETG Commodities, then provided an overview of lentil production in Canada, the world’s biggest pulse exporter, and reported on the recently harvested new crop.

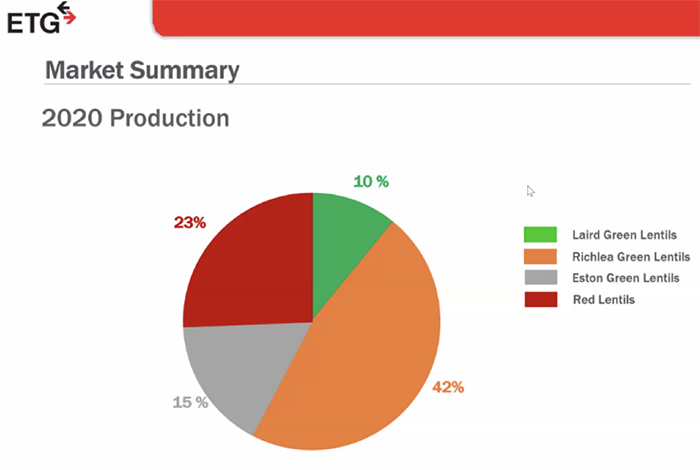

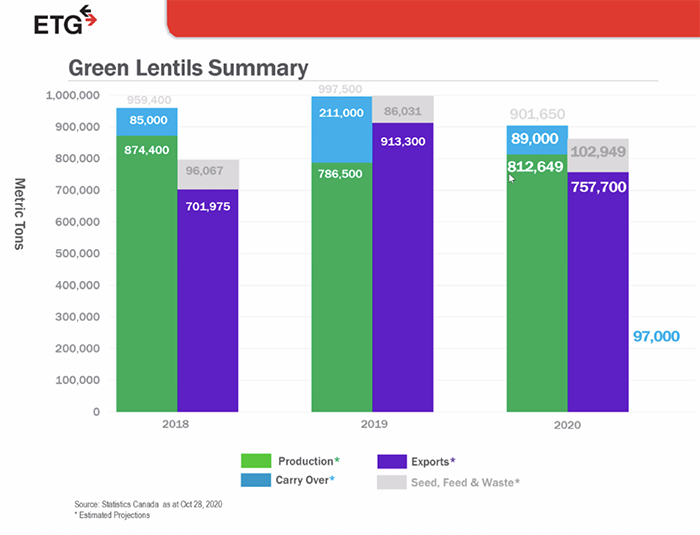

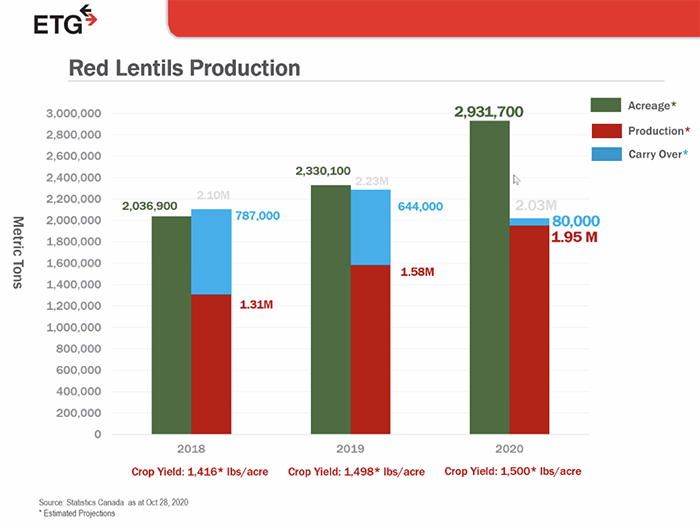

In Canada, lentils are grown primarily in the province of Saskatchewan and, to a lesser extent, Alberta and Manitoba. Several varieties of lentils are produced, including Laird green lentils, Richlea green lentils, Eston green lentils and red lentils. Kapoor shared the following Statistics Canada estimates for 2020:

Kapoor expects Canada’s green lentil exports to amount to about 750,000 MT in 2020/21, leaving a carry-out of 97,000 MT. The supply-demand situation, he said, is balanced and farmers are in no hurry to sell their inventories. About 25-30% of the new crop has already been committed and Kapoor estimates Canada has already shipped 200,000 MT of green lentils. The top buyers are India (projected to import 91,000 MT in 2020/21), Colombia (expected to take 46,700 MT), Algeria (45,000 MT), Ecuador (19,000 MT) and Brazil (13,000 MT).

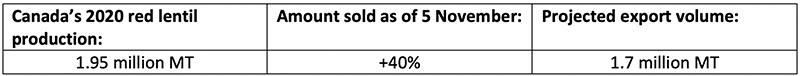

Turning to red lentils, Kapoor presented numbers that represent a consensus among industry members. Production is estimated at 1.95 million MT based on a seeded area of 2.9 million acres and yields of 1,500 lbs/acre. The carry-in is estimated at 80,000 MT, although Kapoor does not believe it is actually that high. Exports are projected at 1.7 million MT, leaving a carry-out of 110,000 MT after accounting for waste and seed and feed use. The main export markets are expected to be India (686,207 MT), Türkiye (325,095 MT), UAE (193,359 MT), Sri Lanka (56,279 MT) and Syria (25,001 MT). However, should the carry-in amount turn out to be lower (as Kapoor suspects) and if export demand spikes (as suggested by Türkiye’s short crop and its lowering of import duty on red lentils from 20% to 9%) then he believes carry-out will be negative and there will be a global shortage.

At the time of the webinar, farmers had already sold more than 40% of their red lentil crop and were in no rush to sell the rest, as prices had been elevated recently by news of import tariff reductions first in India and then in Türkiye, and a pickup in demand from markets like Bangladesh. Kapoor sees farmers holding on to their lentils until April, when they will have clarity on India’s lentil production. He cited CNF prices of $600-625 at present and said the industry expects a spike of about $100 if Australia is not an aggressive player and demand from Türkiye, Bangladesh and other markets picks up.

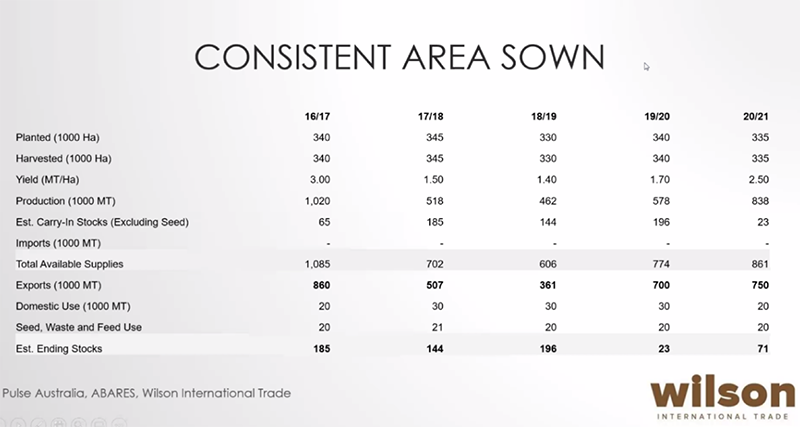

Peter Wilson, managing director at Wilson International Trade, then covered Australia’s 2020 lentil harvest. He began by noting that Australia is the driest continent on the planet and its weather is highly volatile. Moisture, therefore, is the farmer’s biggest limiting resource. On the production side, therefore, Australia’s agriculture sector has relied on plant-breeders to develop drought resistant pulse varieties, and these “unsung heroes” have succeeded in making pulses a more competitive agronomic crop.

Wilson reported that this growing season, there were generally very good climate conditions and high yields are expected for most pulse crops. The pulse harvest is now underway and will get into full swing in the coming weeks. Because of the size of the crop, Wilson foresees the harvest extending through Christmas.

On the marketing side, Wilson noted that Australian growers have the storage infrastructure to store grain on farm in pristine condition through the crop year. They also have the financial capacity to hold onto their lentils and as a result Wilson sees exports being shipped out gradually over the course of the marketing year. Furthermore, Australia’s ability to ship out large volumes in a short period of time is constrained by the limited availability of containers at present, a consequence of increased demand for container shipping capacity in China.

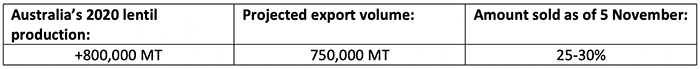

Australia’s lentil production consists principally of red lentils. Although the seeded area remains fairly consistent from year to year, yields vary considerably because of the country’s volatile weather. For 2020/21, Australia’s lentil production is estimated at more than 800,000 MT off of 335,000 harvested hectares and yields of 2.5 MT/ha. Carry-in is estimated at a mere 23,000 MT. Given the size of the crop, Wilson sees the country well-positioned to have a consistent export program over 12 months, with exports projected at 750,000 MT. The main export buyers are Bangladesh, India, Sir Lanka, Pakistan and Egypt. This year, Türkiye is expected to be more active, as well. India’s extension of the lentil tariff reduction through 31 December is unlikely to affect Australia’s export plans, as new crop will not be ready to arrive before the deadline.

According to Wilson, 25-30% of the crop had been sold as of last week. Farmers, he said, are being defensive as they are still smarting from last campaign, when they had poor yields and prices moved against them. Additionally, the logistical difficulties caused by the container shortage have disciplined the market. Export sales are only now starting to move at $600 CFR. Bangladesh has been especially active.

India / IPGA / Canada / Australia / Anurag Tulshan / Dr. S.K. Malhotra / Sunil Kumar Singh / Rakesh Khemka / Rav Kapoor / Peter Wilson

Disclaimer: The opinions or views expressed in this publication are those of the authors or quoted persons. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Global Pulse Confederation or its members.