August 19, 2020

The second edition of this webinar series examines the chickpea outlook for India, Australia, Africa and Russia.

The IPGA Knowledge Series is back! Last Friday, the IPGA hosted the second webinar in the series, this time covering the market outlook for both desi and kabuli type chickpeas in India as well as in the major origins of Australia, the chickpea-growing nations of Africa and Russia.

The webinar was moderated by G. Chandrashekar, senior editor and policy commentator at the Hindu Business Line, and featured a distinguished panel of experts, including:

IPGA Vice Chair Bimal Kothari opened the virtual event by welcoming attendees and highlighting the success of the Knowledge Series debut, which covered India’s recent agricultural reforms and attracted more than 900 viewers from 30 countries.

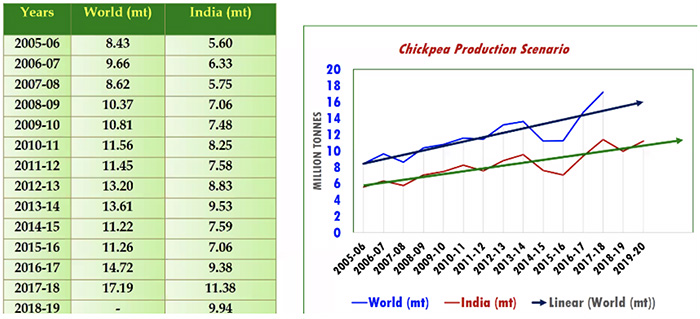

Turning to the subject at hand, Kothari noted that India is the world’s largest producer of chickpeas. The bulk of its production takes place during the rabi season, with the crop harvested during the months of March and April. This year’s rabi chickpea production was estimated at 10.9 million MT. In India, chickpeas are called chana and are consumed across the country, both as dal (split) and besan (ground into flour).

Kothari then introduced the moderator, G. Chandrashekhar, who provided further context for the discussion to follow. India’s chickpea production, he said, accounts for 70% of the world’s total output. What’s more, over the past two years, India’s production has seen massive increases. This trend, Chandrashekhar said, is likely to continue and “ … will have a deep impact on the world’s chickpea trade.”

Chandrashekhar then introduced Dr. Narendra Pratap Singh, the director of the Indian Institute of Pulses Research, who was instrumental in boosting India’s chickpea output.

Dr. Singh began by recapping India’s history with chickpea production. During the Green Revolution, the area dedicated to chickpea production declined as the country prioritized the production of major commodity crops like wheat. In recent years, however, the chickpea area has been expanding and has played a major role in moving the country towards pulse self-sufficiency. Comparing the period between the years 2000-02 and 2017-20, chickpea production increased by 129% to 11 million MT and average yields improved by 32% to 1,067 kg/ha.

This quantum leap in chickpea production, Singh said, was the result of technological advances, the increased availability of quality seed, and supportive government policies. One such advance—the development of chickpea varieties with shorter growing seasons of 90 to 100 days—saw the chickpea growing area shift from the northern parts of the country to the central and southern parts of India. In the case of kabuli chickpeas, there have also been genetic advances that have allowed India to produce larger caliber sizes.

These kinds of advances continue through the present day, with efforts focused on the development of climate-resistant varieties and insect-smart pulses with BT-transgenics. Breeding programs are also developing varieties with upright plant structures for mechanical harvesting, greater nutrient and water use efficiency, and higher nutritional content. The latter is particularly important as India looks to develop a pulse value chain.

READ THE FULL ARTICLE

Sunil Kumar Singh, NAFED’s additional managing director, spoke next about the recent policy decisions in support of chickpea production and consumption. Chickpeas constitute 45% of India’s total pulse production. In just five years, production jumped form 7 million MT to nearly 11 million MT. For these reasons, said Singh, chickpeas are the “king of pulses”.

He then explained that, in order to support farmers, NAFED enters the market when prices fall below the government-established Minimum Support Price. The past three years, NAFED was very active in the market and consequently it held 1.5 million MT of chickpeas at the start of the crop year. So far this year, it has procured an additional 2.05 million MT.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the central government implemented several policies in support of chickpea consumption, including the distribution of 1 kg of pulses to 19.5 million households (originally intended for the months of April through June but since extended through November) and an additional 1 kg of whole chana to migrant workers during the months of May and June. Because whole chana can be distributed quickly without processing, it has become the preferred pulse of public distribution programs.

Given the increased demand resulting from the pandemic, Singh anticipates that inventories will clear out before the next cycle. Without the burdensome carryover of the previous years weighing down prices, this should bring stability to the market. Furthermore, Singh mentioned that India’s central government, as well as state governments, are considering making the COVID-19 pulse distribution schemes permanent.

In closing, Singh reviewed the impact of India’s recent agricultural reforms and emphasized that they create a golden opportunity for investment in India’s pulse industry.

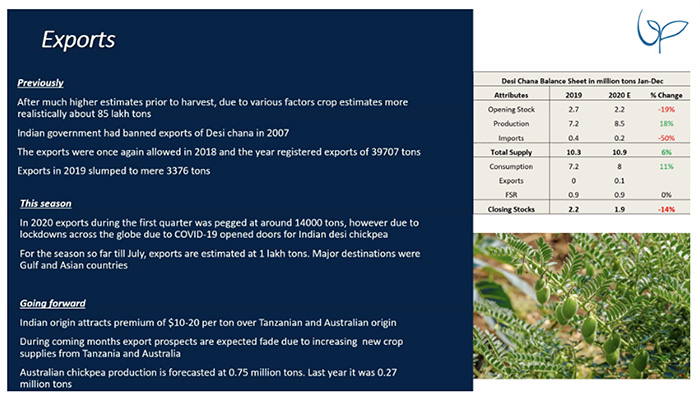

Gaurav Bagdai of G P Agri reported on the market outlook for India’s chickpea crop. In terms of production, India seeded a record 10.7 million hectares to chickpeas in 2019/20, an 11% increase over the prior crop year. The government initially estimated production at 10.9 million MT and the industry projected a more modest crop of around 9.5 to 9.8 million MT. Bagdai, however, reported that yields were impacted by the late withdrawal of the monsoon and complications finding laborers at harvest due to the COVID-19 lockdown. Consequently, production ended up at around 8.8 million MT. Even with this reduced number, the 2019/20 chickpea crop was 16% larger than the 2018/19 crop. In terms of the breakdown by type, desi production increased from 7.2 to 8.5 million MT and kabuli production fell from 400,000 to 300,000 MT.

On the demand side, Bagdai said that due to the pandemic, chana consumption is expected to increase by 11% to 8 million MT this year and to hit 8.32 million MT in 2021. This is driven in part by government purchases for public food distribution programs and also by increased awareness among people across India of the health and nutritional benefits of consuming chickpeas during a public health crisis.

Turning to exports, Bagdai recalled that the 2007 desi chickpea export ban was lifted just recently in 2018. That year, India exported 39,707 MT of desi chickpeas. In 2019, however, exports fell dramatically to 3,376 MT. This year, COVID-19 lockdowns at major origins created new opportunities for Indian chickpea exports. Through July of this year, an estimated 100,000 MT of desi chickpeas have been exported, mainly to markets in Asia and the Persian Gulf. In the coming months, movement is expected to decrease as new crop becomes available from Tanzania and Australia.

Looking ahead, Bagdai said that high MSPs and large government purchases are likely to encourage chana seeding moving forward and thus sustain the chickpea area at this year’s record level.

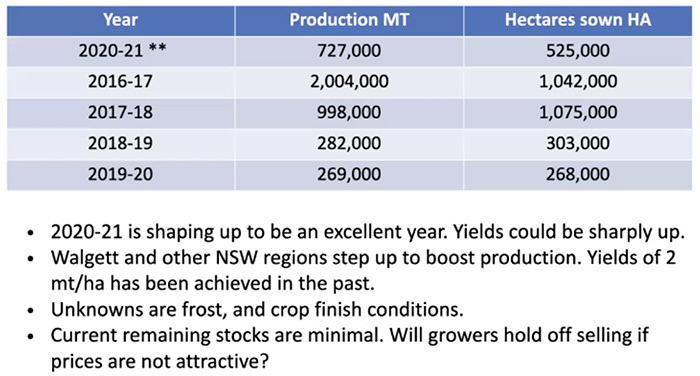

Sanjiv Dubey of GrainTrend provided the market outlook for Australia, the world’s second largest chickpea producer. Australia’s chickpeas are grown in the eastern part of the country. The crop is seeded in April and early May. This year, although parts of the growing region experienced dry conditions, the major chickpea producing areas benefitted from favorable weather. Consequently, although fewer hectares were seeded to chickpeas this year, higher yields are expected and, unless frost hits the crop, production could end up in the 750-800,000 MT range.

With the probability of such a large crop and India out of the market, Dubey posed a rhetorical question: Where will all this production go? Demand from Pakistan and Bangladesh is unlikely to absorb it all. Therefore, he foresees prices falling. Growers, he stressed, will be reluctant to sell at low prices. At the same time, however, they are coming off of two years of drought. Thus far, Dubey reported, 5% of the crop has been sold, but if prices fall, growers may opt to hold onto their chickpeas. There will be significant carryover, he concluded, unless India returns to the market.

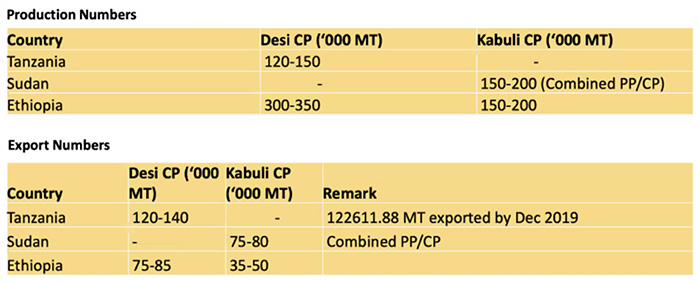

Jayesh Patel, CEO and executive member of the Bajrang International Group based in the United Arab Emirates, reported on the market outlook for African origin chickpeas. He began by observing that global pulse production is not in line with export volumes. India’s imports, he noted, have fallen from 5.6 million MT in 2017/18 to 800,000 MT in 2019/20.

Although Africa’s pulse exports are small compared to those of Canada, Russia, Myanmar and Australia, the countries of Sudan, Ethiopia and Tanzania contribute 300-400,000 MT of desi chickpea exports per year to the global trade. This year, however, because of dry conditions, Tanzania’s production fell off by 50%.

Previously, Africa was a key supplier of pigeon peas to India. But in 2017 India imposed a ban on pigeon pea imports. In response, African growers stopped seeding pigeon peas and began seeding chickpeas for the Indian market, given that at the time chickpea imports were not restricted and were duty free. Since then, chickpea production has been trending upward in the nations of Tanzania, Ethiopia and Sudan.

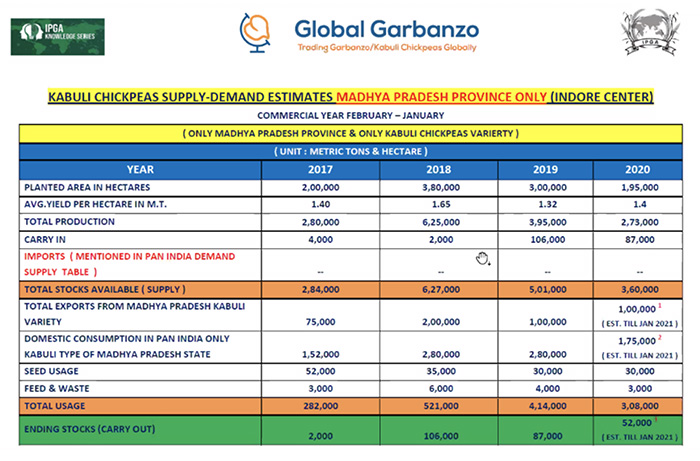

Navneet Singh Chhabra of Shree Sheela International gave an overview of the white chickpea varieties grown in India, including kabuli and Spaniola type chickpeas. India produces 7-8 mm Spaniola chickpeas and large caliber kabuli chickpeas. The large caliber kabuli chickpeas are grown in the state of Madhya Pradesh.

India began the 2020 campaign with a carry-in of 204,000 MT of all the varieties of white chickpeas. This year’s crop amounted to 373,000 MT and together with 4,000 MT of imports, the total available supply for the year totals 581,000 MT, down from 786,000 MT last year.

Looking just at Madhya Pradesh’s large caliber kabuli chickpea crop, this year’s crop amounted to 273,000 MT, down from last year’s 395,000 MT. A carry-in of 87,000 MT brings the total supply to 360,000 MT. Chhabra anticipates exports of 100,000 MT and, subtracting the amount set aside for seed, as well as that used for feed and accounting for waste, he expects a carry-out of 52,000 MT heading into 2021.

On the demand side, Chhabra estimated that white chickpea consumption in the Pan India region will be down 35-40% this year. The decrease, he explained, is due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In the region, white chickpeas are primarily served as a premium product at restaurants and hotel events such as weddings. With national lockdowns in place, the hospitality industry is shutdown. Unless the COVID-19 situation improves and the industry is able to re-open, he estimates 2020 consumption at 265,000 MT, down from more than 400,000 MT the prior two years.

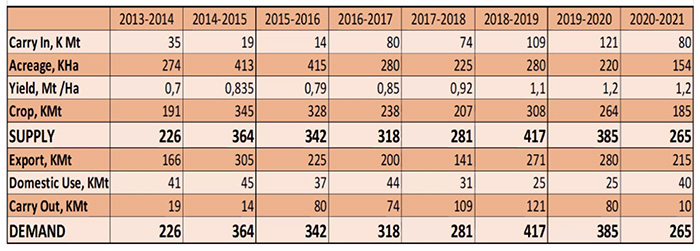

Cem Bogusoglu of G P Global Group based in the United Arab Emirates reported on the market outlook for Russia’s kabuli chickpea crop. Russia produces the smaller caliber kabuli chickpeas, which India uses as a substitute for desi chickpeas.

Bogusoglu began by highlighting the growing uses of chickpeas, from traditional to modern dishes. The rise in chickpea demand led Russia to ramp up its production of kabuli type chickpeas. Its output increased from 5,000 MT in 2004 to 400,000 MT in 2018.

This year, growers seeded 154,000 hectares to chickpeas, the fewest in at least eight years and a far cry form the record 415,000 hectares that were seeded in 2015, when prices were sky high. Russia enters the 2020/21 campaign with a carry-in of 80,000 MT. Its 2020 production is estimated at 185,000 MT. The overall supply this campaign, therefore, amounts to 265,000 MT. Exports are projected to hit 215,000 MT. However, Bogusoglu emphasized, growers are reluctant to sell at low prices and have the facilities to hold on to product for two or more years if necessary.

The major export markets for Russia’s kabuli chickpeas are Tukey (which has taken 41% of Russia’s export availability the past two campaigns), Pakistan, Jordan, India and Saudi Arabia.

IPGA Secretary Sunil Sawla closed out the webinar by thanking Chandrashekhar for moderating the virtual event and each of the panelists for sharing their valuable insights. More than 800 viewers tuned in to watch the webinar live, he said, and informed everyone that the IPGA’s Knowledge Series will continue in early September with a webinar on red lentils.

For a video recordings of the IPGA’s Knowledge Series webinars, including the chickpea webinar covered in this article, visit the IPGA’s YouTube channel.

India / Narendra Pratap Singh / Sunil Kumar Singh / Gaurav Bagdai / Sanjiv Dubey / Australia / Jayesh Patel / Africa / Navneet Singh Chhabra / Cem Bogusoglu / Russia

Disclaimer: The opinions or views expressed in this publication are those of the authors or quoted persons. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Global Pulse Confederation or its members.