April 4, 2023

Dario Bard speaks to Navneet Chhabra about the production volume and quality of India’s 2023 kabuli crop, how markets are reacting and what the industry can expect in the months ahead.

Photo courtesy of Global Garbanzo.

In this instalment of the GPC’s ongoing coverage of kabuli chickpea markets from around the world, Dario Bard speaks with Navneet Chhabra of Global Garbanzo about India’s 2023 crop.

“At the start of the crop year, all eyes were on India,” says Navneet. “The expectation was that we would have a big crop and be able to supply kabuli chickpeas to markets worldwide. In anticipation, traders here sold roughly 25-30,000 MT of chickpeas on forward contracts for shipment in March and April. But yields have been disappointing and now traders are looking to cover their short sales. In response, market prices are going up.”

READ THE FULL ARTICLEIn this instalment of the GPC’s ongoing coverage of kabuli chickpea markets from around the world, Dario Bard speaks with Navneet Chhabra of Global Garbanzo about India’s 2023 crop.

“At the start of the crop year, all eyes were on India,” says Navneet. “The expectation was that we would have a big crop and be able to supply kabuli chickpeas to markets worldwide. In anticipation, traders here sold roughly 25-30,000 MT of chickpeas on forward contracts for shipment in March and April. But yields have been disappointing and now traders are looking to cover their short sales. In response, market prices are going up.”

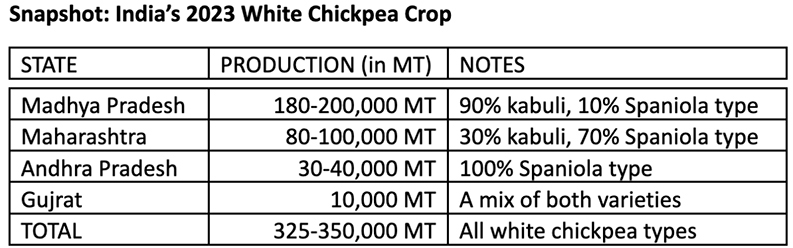

Source: Global Garbanzo

This rabi season, the area seeded to kabuli and other white chickpeas increased significantly. Four states seeded white chickpeas this year. Some increased sowing by 25% and others by 40%. I am estimating a 30% increase in the seeded area overall.

The crop went in the ground during the usual sowing window, which starts in the second half of October and runs into December. Roughly 80% of the crop is normally seeded by the end of November.

In terms of weather, conditions were generally good. But in mid-December, we had a seven-day stretch of unusually high temperatures. At the time, no one thought much of it. But in retrospect, that heat appears to have impacted yields.

At harvest we also had good weather. There was rain in some parts of the growing area, but overall the weather was decent. At the moment, harvest progress stands at 75-80%, which is the normal pace for this time of year. I expect 95-97% of the crop will be harvested by April 15. Some areas may harvest into May, but that would represent a very small portion of the total crop.

To date, farmers have delivered about 100,000 MT to the market. Of that amount, roughly 30% has gone for export, 60% to the domestic market and 10% is being held by traders.

Yields are mostly ranging between 1,350-1,400 kg/ha. That compares to 1,700 kg/ha. last year, which is what we typically get.

The subpar yields can be attributed to the hot spell we had in December. But there is another factor as well. Farmers here are not doing proper crop rotations. They should be rotating chickpeas with alternatives like corn and sugar cane, for instance. However, because most growers are smallholder farmers, it is not easy for them to do that. And because chickpeas are easy to grow, harvest and sell, they plant chickpeas year after year. That is causing yields to deteriorate over the long run.

To sum up then, this year’s yields were below average and this loss in productivity wiped out the expected increased output from the 30% increase in the sowing area. Basically, because India is seeing poor yields, the global kabuli chickpea supply chain is out 100,000 MT of product.

“Basically, because India is seeing poor yields, the global kabuli chickpea supply chain is out 100,000 MT of product.”

The heat in December also affected the size of the grain. Normally, 50-60% of India’s kabuli chickpea crop is of the larger calibers, the 10, 11 and 12 mm sizes. But this year, that percentage is down to 40-50%. This reduction in the production of large sized chickpeas also validates the low yield estimate. Obviously, the fewer the larger sizes, the lighter the kilograms per hectare.

At the start of the crop year, the expectation was that India would harvest a crop of 400-450,000 MT. But with the yields we are seeing now, I am anticipating a crop of 300-350,000 MT. Carry-in is nil. Therefore, supplies are very short in India and imports will be needed to meet domestic demand.

I am projecting domestic demand at 275-300,000 MT, even in the face of high prices.

If we look at the balance sheet, we have production of 350,000 MT at most, and I believe we will be able to import 30,000 MT. Importing kabuli chickpeas will be somewhat of a challenge for India because kabuli chickpea imports from most origins carry a 44% duty. The exception is countries with LDC (Least Developed Countries) status such as Sudan and Ethiopia, but supplies there are limited.

Therefore, with zero carry-in, that brings the total supply to 380,000 MT, which is more or less the supply we had last year. Of that total, I am estimating 40,000 MT will be set aside to seed the 2024 crop, 275,000 MT will go to the domestic market and between 50-75,000 MT will be exported.

“As you can see, the balance sheet is tight and this will keep prices firm.”

In local markets, kabuli chickpea prices were at 145,000 rupees per MT in December 2022 on short supplies. Those prices began to fall in the early part of this year as everyone was expecting a large crop this rabi season. At the start of the crop year, 12 mm chickpeas were going for 105-115,000 rupees. Now they are at 125,000 rupees per MT. Similarly, 8 mm product sold for 75-85,000 rupees and is now going for 87,000 rupees.

Turning to export markets, from January to the Gulfood event in February, India sold around 25-30,000 MT of new crop chickpeas for delivery in March and April. Prices for 12 mm chickpeas ranged from $1,350-$1,400 FOB, and 8 mm chickpeas sold for $950. But now, at the end of March, 12 mm chickpeas are going for $1,525 FOB and 8 mm chickpeas for $1,025 FOB.

In Mexico, they also had a short crop. I don’t think Mexico will export more than 80,000 MT of kabuli chickpeas this year. And now that traders there are seeing a short crop in India, prices for Mexican kabuli increased by $100 per MT. That’s adding fuel to the fire for prices out of India as well.

To sum up then, I see global supplies remaining tight and prices rising. I believe prices will be high in India this year, higher than they were last year. And once India’s supply is exhausted, we will have to see how much other suppliers like Türkiye, the USA, Canada and Russia end up seeding. In my opinion, supplies will remain short over the next five to seven months and prices will stay firm as a result.

“Everyone expected India’s crop would calm the market, but with these yields, India itself will also be looking to import kabuli chickpeas.”

Navneet: We will need to keep an eye on the origins that are going to seed a crop next. In Canada, they are looking to increase the kabuli chickpea area by 30%. We also need to see how much is seeded in Türkiye, the U.S. and Russia, as well. But even if all these origins increase the planted area by 30%, I still foresee a shortage for the next six months, especially of the large caliber sizes.

Everyone expected India’s crop would calm the market, but with these yields, India itself will also be looking to import kabuli chickpeas.

Caption: Photo courtesy of Global Garbanzo.

Disclaimer: The opinions or views expressed in this publication are those of the authors or quoted persons. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Global Pulse Confederation or its members.