April 29, 2020

As demand for pulses spikes around the world in reaction to the coronavirus, the GPC takes a closer look at the phenomenon in this major dry bean consuming region.

Consumers across the globe are stocking up on food essentials, including pulses, as governments institute lockdowns and other measures to contain the spread of COVID-19. Dry beans especially have been flying off store shelves.

In the U.S., Nielsen data for the week ending March 14 shows retail sales of dry beans and chickpeas jumped 230% and 157%, respectively. To keep up with the buying frenzy, Indianapolis-based NK Hurst has been working overtime to package nearly a million pounds of dry beans a week. Across the border in Canada, Agrocrop Export, the country’s largest supermarket supplier, reports customer demand for beans is up by 500% to 1,000%. In India, the Department of Consumer Affairs reports pulse prices have risen 5 to 8% from March 15 to April 3 as shoppers bump up the volume of their purchases. And in Australia, export prices on chickpeas, faba beans, lentils and mung beans jumped by $50 - $150 as international buyers look to bolster their inventories.

It is a phenomenon that has gripped Central America as well, a region that is one of the world’s leading dry bean markets.

In Central America, red and black beans are regularly consumed as part of multiple daily meals. In most of the countries of the region, consumption exceeds production. In Costa Rica, El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala, for instance, imports are needed to supplement domestic production and satisfy internal demand.

The region’s biggest bean importer is Costa Rica, which typically brings in about 40,000 MT of beans a year, mainly from Nicaragua, the U.S. and Argentina. El Salvador follows, usually importing more than 25,000 MT of beans a year. Honduras imports roughly 13,000 MT of beans a year and Guatemala imports 12,000 MT per year on average.

On the other hand, Nicaragua not only harvests enough beans to cover its internal demand, but it also usually has enough of a surplus to make it the region’s main supplier of beans. The country grows both red and black beans, but is mainly a red bean supplier. Its unique rojo seda red bean variety is highly demanded in Central America.

Except for Nicaragua, the countries of the region have instated a variety of actions aimed at preventing the spread of the pandemic, including quarantines, border closures, curfews and travel restrictions. On March 12th, seven of the eight nations of the Central American Integration System (SICA)—Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama, Belize and the Dominican Republic—adopted a declaration of cooperation, committing to joint action to address the COVID-19 pandemic at the regional level.

At the national level, several governments took additional actions to address their food security needs. El Salvador, for instance, the one SICA country that did not sign on to the regional declaration, waived import duties on several essential food items, including dry beans. In Honduras, the government banned the export of red beans.

Across the region, the private sector responded as well. Walmart stores throughout Central America, for instance, have taken to limiting the number of units of essential food items that customers can purchase.

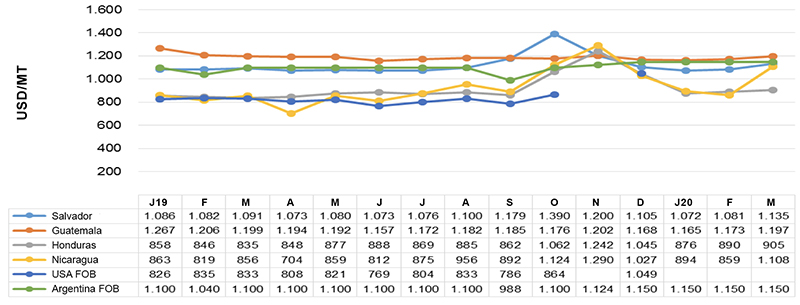

As in other parts of the world, consumers responded by stocking up on food essentials, especially beans. This uptick in demand pushed up prices. Costa Rica’s National Production Council (Consejo Nacional de Producción, CNP) reports that during the month of March wholesale bean prices increased throughout the region. According to the CNP’s latest report, Nicaragua’s export prices for red beans rose to $1,150 per MT in March, a 29% increase from February. In El Salvador, red bean prices rose 5%, while in Guatemala and Honduras they climbed 2%. In Costa Rica, retail prices for red beans increased by 4%, and black bean prices rose by 3%.

To get a better sense of the situation on the ground, the GPC reached out to sources in Costa Rica, Nicaragua and Belize, three countries that signed on to the regional cooperation accord, to find out how the pandemic impacted the pulse sectors there.

Imported red bean prices by market. Source: Costa Rica’s National Production Council

The latest report from the CNP estimates Costa Rica’s 2019/20 (July through June) dry bean production at 9,077 MT, a 17% increase over the previous cycle thanks to improved yields. In 2019, imports totaled 36,967 MT. For the first three months of 2020, they amounted to 9,085 MT. The CNP expects that existing inventories (15,182 MT), domestic new crop arrivals from April through June and import commitments should cover demand through the end of June.

At the same time, however, the CNP acknowledges that demand was atypically high in March, with bean sales jumping by 30 to 40%. The CNP attributes this increase to the fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic. Costa Rica declared a national lockdown on March 18 and, the CNP reasons, the demand spike reflects the increased number of people staying in and cooking at home. On top of that, school meal and other government food programs have increased their buying to stock up for the pandemic, as well.

Beans, though, were not the only pulse that saw demand spike, indicates Jorge Chaves, general manager at Comercializadora Internacional de Granos Basicos, a processor and packager of commodities, including rice and beans. When lentils and chickpeas are factored in, the March increase in overall pulse demand rises to 60%, he says.

“In one week, we sold as much as we usually do in three months,” Chaves reports, adding that Granos Basicos’ lentil and chickpea inventories have cleared out and he is presently securing fresh chickpea supplies from Argentina.

In fact, in the face of the March boom, buyers across Costa Rica are busy acquiring new crop red beans from Nicaragua and black beans from the U.S. and Argentina.

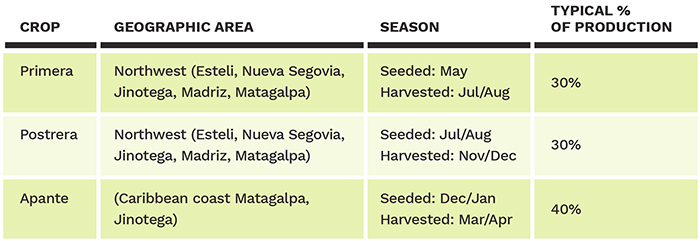

Nicaragua’s privileged geographic location and diverse microclimates enable it to grow three crops a year. For 2019/20, the Ministry of Agriculture estimates overall bean production at approximately 200,000 MT, with an export availability at 70,000 MT.

However, these figures should be viewed with skepticism, cautions Gersom Zeledón, CEO of Multiagro Foods & Coffee, an exporter of commodities such as dry beans and coffee, among others.

“The Ministry of Agriculture’s production estimate is within the national historic range, but this is the best-case scenario,” he says. “We must keep in mind that the government wants to paint the best picture.”

In Zeledón's opinion, the official figures are based on the most optimistic seeded area estimate multiplied by a yield factor that does not reflect the reality on the ground. Beans in Nicaragua are grown by smallholder subsistence farmers, he explains, who regularly plant seed from the previous harvest and forego fertilizers and other inputs due to their limited financial resources. Further, the country’s irregular weather patterns put crops at an elevated risk of losses, particularly for Nicaragua’s underdeveloped farm sector. Taking these factors into account, Zeledón indicates that industry members believe the actual yields will 80% of what the Ministry announced.

Presently, Nicaragua is harvesting its Apante crop. Asked about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the sector, Zeledón says that business continues as usual. In line with SICA’s declaration of cooperation, Nicaragua’s trade within the region has been unhindered. And unlike the other Central American countries, Nicaragua has not implemented restrictive measures on its population. Instead, it is broadcasting prevention and information campaigns on state-owned media.

The public response to these campaigns has been to shelter in place and stock up on staple food items, including beans, an essential part of the regional diet. This at a time when buyers from other Central American markets have increased their demand based on the panicked buying in their own countries. Zeledón estimates demand for Nicaraguan beans has risen by 20 to 30%.

Additionally, he points out that Nicaragua is the only Central American country with a summer crop (the Apante crop) and, therefore, in the absence of new bean crops from other countries in the region at this time, the pressure from regional export markets has sent Nicaraguan bean prices soaring by 70% since early March, when the pandemic first arrived in Central America.

“And we still have new crop arriving from the Apante harvest,” says Zeledón. “Imagine what will happen to prices once this season ends.”

Source: Gersom Zeledon, Multiagro

Source: Gersom Zeledon, Multiagro

Like Nicaragua, Belize is a net dry bean exporter. Although it is geographically located on the Central American isthmus, it has closer ties with the nations of the Caribbean because of its history as a former British colony. Consequently, its major export markets are primarily in the Caribbean.

GPC reached out to Lyell Banman of Bel-Car Export & Import, a leading Belizean dry bean exporting company, to see how the COVID-19 pandemic was affecting the pulse industry there.

Banman reports that Belize wrapped up its bean harvest in February. This year, he says, the crop turned out much smaller than normal for both light red kidney beans and black-eye beans, the two varieties Belize commercializes.

In the case of light red kidney beans, the main factor behind the reduced production was the loss of area to soybeans, which saw heightened demand. Other crops also took hectares away from light red kidney beans.

“What happened this year is that in late 2019, the corn crop here got hit hard by drought, and when January came around, a lot of growers, instead of planting light red kidney beans next, tried to recoup their losses by either planting corn again or planting sorghum,” Banman explains.

The black-eye bean crop, on the other hand, was coming along nicely, he relates, until the plants received excessive moisture and stem rot set in.

As a result, Banman estimates the light red kidney bean crop at 3,000 MT and the black-eye bean crop at 1,500 – 2,000 MT. Normally, Belize produces 5,000 MT of each bean variety.

Asked if he has seen increased demand from Central America, Banman replies that Belize does not usually export to Central America, although some Belizean light red kidney beans do tend to make it over to Guatemala through informal cross-border trade. This year, though, there was a bit of an uptick in demand from Guatemala, he indicates, but it was short lived as the government of Belize quickly halted all light red kidney bean exports for food security reasons.

Black-eye bean exports, however, were allowed to continue because that bean type is not consumed in Belize.

The question of the moment is whether the increase in demand reflects a one-time spike due to panicked buying or sustained demand as people adopt new eating habits in response to the pandemic.

“The lockdown here in Costa Rica began three weeks ago and it saw a notable increase in legume sales,” says Chaves. “We are waiting to see if the increase was only to stock up or if people will be consuming more legumes while they stay at home.”

The CNP expects demand will return to normal levels moving forward. It arrived at this conclusion in part by reasoning that increased unemployment will diminish the buying power of a good number of people in the weeks ahead. On top of that, Chaves notes a drop in demand from other buyers, such as those in the hotel and restaurant sectors.

“In Costa Rica, we have these small shops, locally referred to as sodas, that typically serve breakfast and lunch. They are closed now and so there is less demand from there, too,” he notes.

In neighboring Nicaragua, Zeledón tells us the country has sufficient bean inventories to cover three months of demand, but if export demand continues to increase, supplies will be extremely tight.

In May, Nicaragua will seed its Primera crop. Given the Apante crop’s high prices, growers are excited about planting beans. However, Zeledón warns, “Let’s remember that given the climate conditions during the Primera season, the risk of losses is likely. Our hope is that the Primera harvest will replenish inventories in August, but we need to consider the climate risk and the possibility of sustained strong demand.”

black beans / red beans / Nicaragua / Costa Rica / Guatemala / Belize / Honduras / El Salvador / Costa Rica’s National Production Council / Gersom Zeledón

Disclaimer: The opinions or views expressed in this publication are those of the authors or quoted persons. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Global Pulse Confederation or its members.