June 2, 2021

With India out of the picture, will the Black Sea region see a reduction in the area seeded to pulse crops this year? The GPC reaches out to sources in Russia, Ukraine and Kazakhstan to find out.

The planting of pulse crops is well underway in the major pulse-producing countries of the Black Sea region. Early on, cool temperatures and wet conditions in some areas delayed the start of the sowing season, but growers have since made good progress in the weeks that followed.

Russia is the Black Sea region’s major pulse producer. Dmitry Rylko, the director general of the Institute for Agricultural Market Studies, indicates growers in the country’s southern pulse growing areas have wrapped up the planting of their yellow peas, lentils and chickpeas. Farther north, in Western Siberia, seeding is just now getting started.

Over in Ukraine, Sergey Feofilov, the founder of UkrAgroConsult, reports that a cold and wet spring delayed the seeding of chickpeas and lentils, but not yellow peas and kidney beans. Planting is nearly wrapped up for all pulses except yellow peas, which may have another week to go.

In Kazakhstan, cold temperatures delayed the start of the sowing season, but at JSC Atameken-Agro, Kintal Islamov, the company’s chairman, expects seeding to wrap up by May 25th. That would be the same date as last year, when growers got an early start on planting, he notes.

The main pulse crop grown in the Black Sea region is the yellow pea. Other pulses produced in significant volumes include chickpeas, lentils and, in Ukraine, kidney beans. Below we take a closer look at the seeding of these crops in three of the region’s major pulse-producing countries.

The cool and wet conditions this spring not only delayed the seeding of crops in Russia, but, at least in the key pulse-growing region of Rostov, also kept growers from fulfilling their planting intentions.

“Conditions there were very wet, and growers weren’t able to get in the fields in a timely manner,” relates Rylko. “It is too early to tell how much went unseeded, but they definitely weren’t able to plant all the pulses they had planned to.”

Despite the late start and difficult conditions, Rylko estimates the area seeded to pulses this year is up 5-10% over last year, with increases in the key yellow pea growing areas of Stavropol and Krasnodar. In the case of the latter, the yellow pea area is estimated at 88,000 ha., an increase of 12,000 ha. over the previous year. The expansion in the area is explained by high prices for all pulses during 2020-21, the unusually high rate of winter wheat re-seeding in some areas and the new taxes the government of Russia announced it will impose on wheat, corn and barley exports starting June 2.

A good part of Russia’s pulse production is destined for export. In the case of chickpeas and lentils, approximately 85-90% of production is exported. In the case of yellow peas, however, 60-70% of production is consumed domestically, both as food for human consumption and as livestock feed.

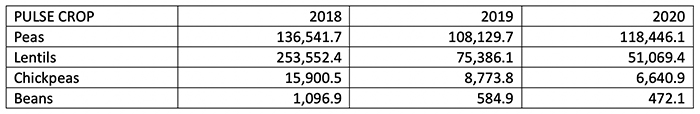

Russia typically exports 1 million MT of pulses per year. Thus far in 2020-21, Russia’s yellow pea exports have amounted to 740,000 MT. The top buyers have been Pakistan (170,000 MT), Italy and Türkiye (each taking 130,000 MT). Chickpea exports have amounted to 255,000 MT; despite the high tariffs, India has been the biggest buyer of Russian chickpeas, taking 75,000 MT. Lastly, lentil exports have amounted to 55-60,000 MT, with Pakistan and Türkiye the main buyers.

“Pakistan had a poor crop and imported about 200,000 MT of Russian pulses,” says Rylko. “This was the first time in history Pakistan entered the Russian market so aggressively.”

Inventories for all three pulses are nearly cleared out and Rylko expects Russia will enter the 2021-22 marketing year with zero ending stocks.

As for Russia’s 2021 pulse production, it is still too early to say how the crop will turn out, especially for the country’s chickpea and lentil crops, which were just recently seeded. On yellow peas, Rylko indicates that the crop in southern Russia, where most of the export supply is produced, is currently in good condition.

“The weather has been good for the most part, maybe a bit too cool. We need some additional heat units. But in general, the crop is fine,” he says, but then adds, “These are capricious crops. They don’t tolerate extreme heat or excessive rain. Going forward, we have to watch what happens very carefully to determine what we can expect of this year’s crop.”

Ukraine had a long, wet and cool spring season that caused planting delays, especially in the central and western part of the country, where muddy ground made it a challenge to get equipment into the fields. In the south, conditions were more favorable, and growers were able to seed their pulses earlier.

“There was stiff competition for acres this year,” says Feofilov. “COVID-19 drove up the price of major commodities like corn and sunflower, which saw tremendous increases in planted hectares. This was one of the most important factors influencing farmers’ planting decisions this year.”

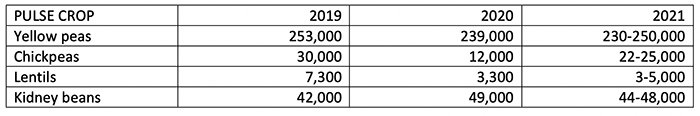

Feofilov estimates this year’s yellow pea area will end up at around 230-250,000 hectares, similar to last year. He expects 22-25,000 hectares will be seeded to chickpeas, up slightly from last year due to an improvement in prices and good export demand. The area seeded to kidney beans, he projects, will be similar to last year; Feofilov estimates it at 44-48,000 hectares. The lentil area, however, declined considerably not only because of dampened market expectations due to the high tariffs in India, but also because of a short supply of good quality seed. The shortage of high-quality seed is the biggest challenge facing all pulse crops in Ukraine, says Feofilov.

Over the next three to four weeks, the crops will require additional rains. Besides the weather, Feofilov is also keeping an eye on the price of inputs, such as fuel, which could limit fieldwork if they become too expensive.

On the marketing side, Ukrainian pulse traders are hopeful that India will continue to ease restrictions on pulse imports. They also have their eye on China, where there is strong demand for yellow peas for both human consumption and livestock feed.

“It’s a long process,” says Feofilov. “The Ukraine Pulses Association is active in consulting with authorities in China on how to speed up the process and the paperwork.”

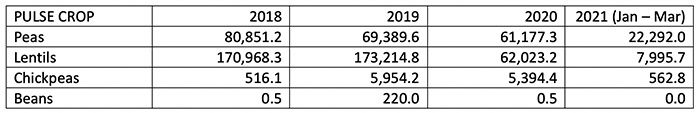

In 2020-21, Ukraine exported 320,000 MT of yellow peas through April. By the end of the marketing year, Feofilov expects another 20-30,000 MT will be exported as well. He projects chickpea exports will total 25,000 MT; so far, about 18,000 MT have been exported. On kidney beans, he is projecting exports of 18,000 MT. And on lentils, he explains that the 2020 crop was small, no more than 3,500 MT, and therefore he expects exports of 1,500 MT or less.

Based on his calculations, Feofilov estimates Ukraine will finish the 2020-21 campaign with ending stocks of 12,000 MT of yellow peas, 20,000 MT of chickpeas and 25,000 MT of kidney beans. The main buyer of Ukrainian kidney beans is the European Union, but Feofilov notes that domestic consumption is on the rise, as well.

“Last year, Ukraine produced 75,000 MT of kidney beans and more than half were consumed domestically,” he says.

Kidney beans are part of the traditional Ukrainian diet, but Feofilov indicates the increased consumption is also due to a growing trend towards healthier diets.

“But right now, domestic food inflation is high in Ukraine. This is one of the negative impacts of COVID-19,” says Feofilov. “It is hoped that once the population is vaccinated, we will see a revival of this trend.”

In Kazakhstan, despite a late start, more than half of most pulse crops have been seeded. The lone exception is the chickpea crop, which was seeded later as growers waited for warmer conditions. Compared to last year, Islamov reports that the area seeded to yellow peas has decreased, while that seeded to lentils and chickpeas increased.

“This is because lentils and chickpeas proved to be more profitable than peas, even though there’s strong yearly demand for peas from Afghanistan,” explains Islamov.

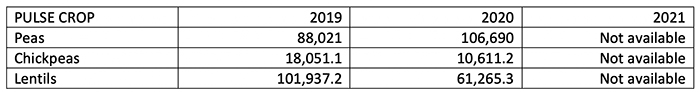

Pulse production has been in decline in Kazakhstan in recent years as growers have shifted to more profitable options, mainly oilseeds, such as linseed and rapeseed. In 2018, the country seeded 424,500 hectares to pulses. That area fell to 210,800 ha. in 2019 and 181,000 ha. in 2020.

According to the National Statistics Committee, thus far in marketing year 2020-21, Kazakhstan has exported 44,621 MT of yellow peas, 27,199 MT of lentils and 3,391 MT of chickpeas. Islamov expects little carryover heading into the new cycle.

Russia / Ukraine / Kazakhstan / Black Sea Region / Dmitry Rylko / Sergey Feofilov / Kintal Islamov

Disclaimer: The opinions or views expressed in this publication are those of the authors or quoted persons. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Global Pulse Confederation or its members.