January 25, 2021

Favorable weather resulted in high yields and excellent quality across pulse crops, but there have been logistical hiccups.

Faba bean harvest. Photo courtesy of Agri-Oz.

In its December crop report, ABARES projected that Australia’s winter crop production would be up 76% on the year due to favorable weather. But, at least in the case of winter pulses, even with this sizeable increase, the government’s figures appear to have undershot the mark.

Back in December, ABARES had pegged the chickpea crop at 737,000 MT, the lentil crop at 616,000 MT, the faba bean crop at 516,000 MT and the field pea crop at 287,000 MT. But industry sources consulted by the GPC cited considerably larger production estimates. Across the board, these insiders believe yields ended up better than what ABARES forecast.

“The problem with estimating yields in Australia is that we have great variability in weather even across short distances,” explains Mostyn Gregg of Agrocorp International. “You can drive a mile and find widely different conditions, and they can also vary greatly from year to year in any given area.”

This harvest season, the pulse crops were so large that it took longer than usual to finish combining them. That delay was then compounded by difficulties securing containers at port, an especially frustrating and costly dilemma given that Ramadan comes early in 2021.

“Container freight continues to be a major problem,” says Peter Wilson of Wilson International Trade. “Cancelled bookings, freight price hikes, equipment supply shortages combined with large demand, reduced shipping capacity and longer transit times is all adding extra complexity to contract execution.”

There is no doubt the COVID-19 pandemic has caused significant disruptions to global trade, but at Agri-Oz, Francois Darcas believes there is more to it than that.

“I think we are seeing the consequences of consolidation,” he explains. “The main lines have more pricing power and are able to dictate terms and reposition equipment on the most profitable routes, namely China to Europe and North America.”

Australia has also had problems of its own, with a dockworkers’ strike disrupting service at major ports.

“A lot more pulses will ship in bulk this year,” says Darcas, “firstly because container shipping is so difficult and delayed, and secondly because our big crops make it easier to accumulate large quantities.”

Below, we take a closer look at each of Australia’s major pulse crops.

“The rule of thumb is that big crops get bigger,” says Wilson at Wilson International Trade referring in general to Australia’s pulse and grain crops this year. “The harvest was a little later as a result of a good growing season pushing out maturity of the crops.”

With the exception of Queensland, which was a bit dry, the country’s pea and chickpea growing areas benefitted from timely rains. Wilson says it is likely Australia’s chickpea and pea crops ended up larger than what ABARES forecast. This was evident back in September as well when Wilson participated in the Pulses 2.0 Desi Chickpeas Global Outlook panel and suggested Australia’s chickpea production was likely closer to 900,000 MT than the earlier estimations of 750,000 MT.

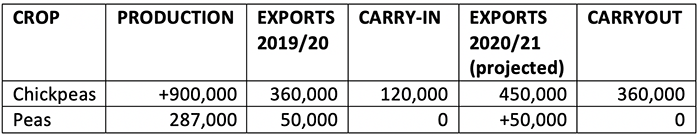

In 2019/20, Australia’s chickpea exports amounted to 360,000 MT and its field pea exports totaled about 50,000 MT. By Wilson’s estimations, that leaves Australia with a carry-in of 120,000 MT on chickpeas, which would put the overall supply at more than 1 million MT. In the case of peas, Wilson indicates any old crop inventories that were not exported were likely redirected to the domestic stockfeed market.

Australia therefore enters the 2020/21 crop year with a large supply of chickpeas, which could be problematic given that India, Australia’s biggest chickpea buyer, is expecting a large chickpea crop of its own this rabi season and is therefore unlikely to lower its 60% duty on desi chickpea imports any time soon.

Wilson sees Australia’s 2020/21 field pea exports possibly exceeding last year’s volume of 50,000 MT, with the main buyers in South and Southeast Asia, but says the bulk of the crop will go to the domestic stock compounding and feed industries. As for chickpeas, he projects exports to grow to 450,000 MT, with the main buyers being Bangladesh, the UAE and Pakistan. By his calculations, that would leave a carryout of about 360,000 MT.

Wilson, however, is of the opinion that Australian growers are prepared to take a long-term view and have the capacity to store their chickpeas in good conditions. They also have access to financial tools that remove the pressure to sell at unappealing prices.

“Australian farmers have demonstrated tremendous patience historically,” he concludes.

He cites current CFR prices on chickpeas at around $570/MT.

Peter Wilson of Wilson International Trade.

Australia’s lentil production is almost entirely of the red variety. This year, Gregg at Agrocorp reports that the weather conditions at harvest were ideal for the most part, except for a wet finish that caused some delays and saw growers rush to get their lentils off. Those minor issues notwithstanding, the quality of new crop red lentils is, in Gregg’s words, “superb”.

“I believe this is Australia’s second largest lentil crop on record,” he says. “Second only to the 2016/17 crop.”

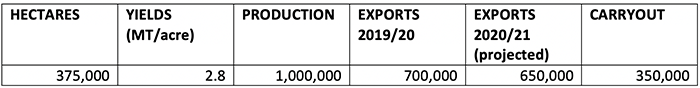

According to his own calculations, Australia produced a lentil crop of about 1 million MT. He arrives at this figure based on a seeded area estimate of 375,000 hectares (up 17% over his seeded area estimate for the prior year) and an average yield of 2.8 MT per hectares, a reflection of the favorable weather as well as a testament to the successful development of varieties with improved yield potential.

Gregg admits that his seeded area number is higher than what most others believe actually went in the ground, but he stands by it, citing the accuracy of his supply-demand calculations over the course of the past decade.

“Because of China’s imposition of a tariff on barley in April, a lot of barley hectares switched to red lentils,” he explains. “If anything, I would say my area estimate is conservative.”

Because of the increased area and the atypically high yields, the harvest took longer than usual.

“This year, we had lentil plants that kept on re-podding. That maximized yields but the harvest dragged on longer than usual because of it.”

The drawn-out harvest set the export program back about six weeks.

“It’s a massive issue because everyone wants the frontend. COVID has exacerbated this, but the pulse market is a just-in-time market. It is cashflow poor and people don’t want to have cash tied up in stock,” he explains.

On top of that, containers are proving hard to come by in Australia, making it difficult to move such a large crop.

“This is the worst execution year I’ve ever had. It’s a disaster,” says Gregg.

Australia enters the 2020/21 marketing year with negligible carry-in on red lentils, as the spike in consumption caused by the pandemic combined with low prices helped Australia move 700,000 MT of red lentil exports in 2019/20. Gregg projects red lentil exports this cycle will amount to about 650,000 MT.

“The Ramadan countries are the main consumers for red lentils and a lot of that demand has already been sated,” says Gregg. “Both Türkiye and India are well covered. They can take bulk vessels and they bought early. Our biggest buyer is Bangladesh because of the varietal types we grow, but that market is starting to feel sated. Now we are basically selling into Pakistan.”

Gregg cites current FOB prices on new crop red lentils at $565/MT. Normally Australian red lentils sell at a premium over Canadian product because they have a lower moisture level. But this year, because of the size of Australia’s crop, there is a discount, explains Gregg. Even so, growers are seeing good returns on their lentils thanks to the high yields. At the same time, though, they are in no rush to sell, as other crops, such as flax, wheat and canola, offer even higher returns.

With Ramadan beginning in April this year and celebrating countries already stocked up, Gregg anticipates a slow period for red lentils from March to May and forecasts a carryout of 350,000 MT, which will likely see hectares revert to barley next winter.

“We will be back to the seeded area we had before and it will all depend on yields,” says Gregg. “If we have good weather, we will be looking at onerous production in 2021/22.”

Mostyn Gregg of Agrocorp.

As with the other pulse crops, this year’s faba bean crop benefitted from favorable weather. Francois Darcas of Agri-Oz Exports reports that the harvest went well, with the exception of the crop in New South Wales, where untimely rains and a disease outbreak damaged part of the crop.

“It is hard to quantify, but perhaps some 30,000 - 40,000 MT will not be suitable for export and go into the feed market,” he says.

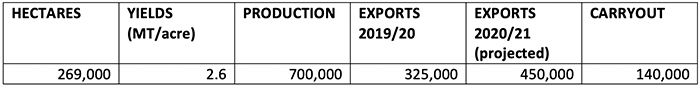

Elsewhere, the good conditions produced a good quality crop and pushed up yields. Darcas has heard growers speak of yields ranging from 2.5 to 6 MT/ha. The consensus among industry members is that 700,000 MT of faba beans were harvested this year. Taking ABARES’ area estimate of 269,000 ha., that would mean yields averaged 2.6 MT/ha., which Darcas sees as very possible.

In 2019/20, Australia exported 325,000 MT of faba beans, leaving minimal carry-in for this crop year. Darcas estimates no more than 10,000 MT of old crop remains. He reports good movement early on to Egypt (Australia’s principal faba bean export market) and to other regular buyers, such as the UAE, Saudi Arabia and Vietnam.

“I would expect a higher volume of exports this year given the greater availability,” says Darcas. “The last time we had such a sizeable crop was in 2016/17. Australia exported 461,000 MT then and was still left with a large carryout.”

The strong pace of exports is likely driven by relatively low prices. Darcas cites current FOB prices at $315/MT.

Francois Darcas of Agri-Oz.

Faba bean field. Photo courtesy of Agri-Oz.

Australia / ABARES / lentils / faba beans / field peas / Mostyn Gregg / Peter Wilson / Francois Darcas / Egypt

Disclaimer: The opinions or views expressed in this publication are those of the authors or quoted persons. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Global Pulse Confederation or its members.