August 4, 2022

Jesse Sam spoke to Sachin Khurana, India Representative of the USA Dry Pea and Lentil Council to get an update on Kharif planting and learn about the factors that affect farmers’ choices and yield outcomes.

India’s geographical size means that its climate is complex and diverse: the country covers nearly 3.5 million square kilometres, or 2% of the world’s total landmass.

Different regions experience different weather patterns, which influences when and where different types of crops are sown and harvested.

India has two categories of crop: kharif and rabi. Kharif crops — which include rice, maize, soybean, groundnut, cotton, moong beans, and pigeon peas — are predominantly planted across the south of the country in the rainy (monsoon) season, which runs from June to October.

Rabi crops — which include wheat, barley, cereals (oats), pulses (urad and moong beans), and oilseeds (mustardseed) — are planted in the winter (October to March), predominantly across the north of the country.

During Kharif season, farmers’ fortunes — and the country’s food supply — depend on reliable rains. This year is no different. Producers were relieved to hear that the national weather service (known as the India Meteorological Department, or IMD) forecast that rainfall would be within a normal range for 2022.

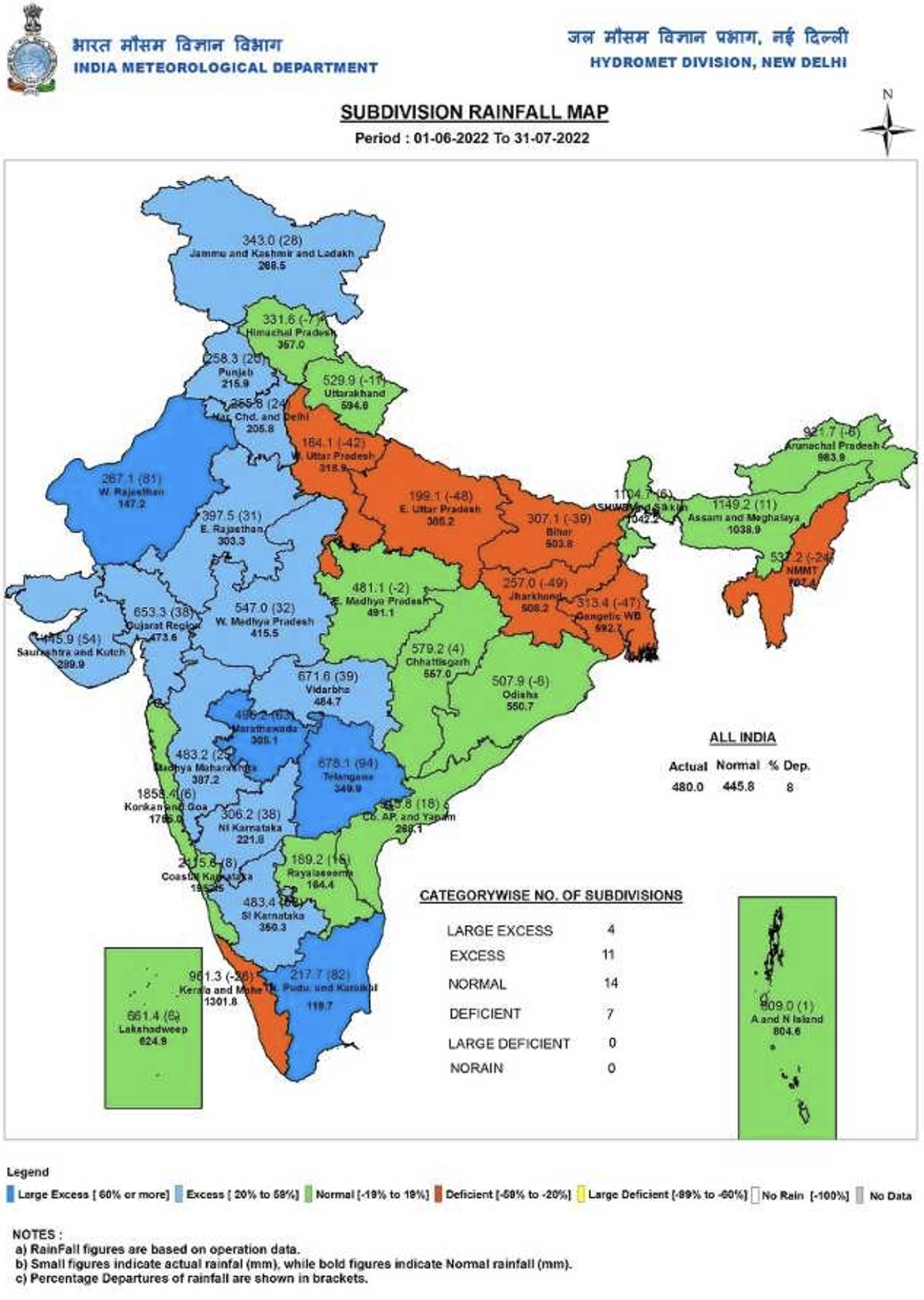

Back in May, IMD forecasts suggested that this year’s monsoon season would see rains at around 3-4% higher than the long-term seasonal average. Data from the end of July — the midway point of monsoon season — shows that national rainfall is actually 8% higher than normal.

But the southern peninsular — where kharif crops are predominantly planted — has experienced particularly strong showers, with rainfall nearly 30% higher than normal between June and July (467mm actual, compared with 366mm average).

According to Sachin Khurana, India Representative of the USA Dry Pea and Lentil Council based in New Delhi, the positive weather patterns will increase individual farmers’ choice, as they will be able to select the most lucrative crops to plant. But the increased choice, in his view, will not lead to a significant increase in overall planting or production levels. “We don't really expect a drastic change in the acreage from last year. I think it's going to be at a similar level, or 5 to 10% in either direction,” he told GPC.

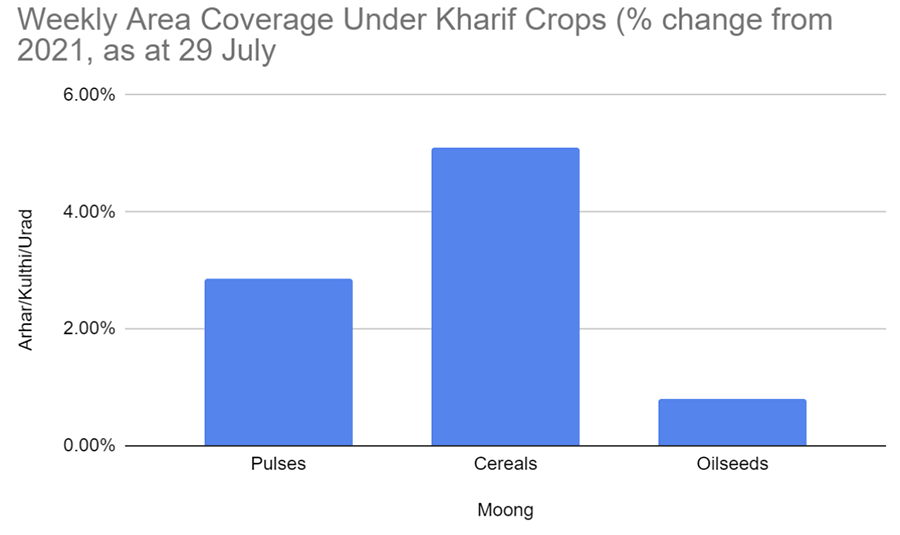

The latest data from the Department of Agriculture support Khurana’s analysis. As the graph below shows, the change in total area sown across pulses, cereals, and oil seeds from 2021 has been modest. Among the major pulses, pigeon peas (-14%), horse gram (-31%), and moong beans (16%) have seen the largest increases in acreage this year.

Source: Department for Agriculture and Farmers Welfare

Khurana points out that, when thinking about the monsoon season and sowing data, regional variation is just as important as overall volume. “It’s not just the amount of rain but how it's distributed in terms of geography,” he said.

Time matters, as well. “Periodicity also has an impact on Kharif crops. You might have a week of very high rainfall and then two weeks of no rainfall, that doesn't work well for crops. So it's not just overall rainfall we look at, but how it's distributed across time and across geographies.”

The IMD’s sub-divisional rainfall map, copied below, provides a granular look at how rainfall patterns have varied across the country’s 28 states since 1 June.

States throughout the southern, central, and some parts of the northern regions have experienced the heaviest rainfall this season. Eastern states, by contrast, have been much less wet.

The eastern state of Odisha is a prime example of regional distribution and periodicity affecting planting. In June, the state’s rainfall was nearly 40% below the median monthly level; several parts of the state did not see rains until 12 days after the start of the monsoon season. Then, between 9 and 18 July, there was more than 200mm of rainfall. By the end of the month, the state had a 2% surplus of rain, according to IMD data reported by DownToEarth.

Such erratic weather patterns make farmers’ lives much harder. As a result, Odisha was well-behind on its rice paddy sowing targets by late-July: 1.27 million hectares sown, compared with 3.5 million hectares planned.

It’s not just the rains that shape farmers’ planting decisions. Khurana points out that policymakers can shape the investment climate, too.

For 2022, the Indian government increased the minimum support price [MSP] for kharif crops by around 4-9%. Moong bean is the pulses crop which saw the highest MSP increase, by nearly 7%, to around $98 per 100kg. During this Kharif season, total acreage of moong beans has increased by 16% (from 2021) — that is the highest increase of any major Kharif pulses crop.

“When the government increases MSP — irrespective of the percentage — it motivates farmers to grow more of that crop, because they know they're going to get higher returns on it.”

But Khurana notes that wider market data will always factor into the equation. At the end of the day, he says, farmers ask themselves: “Where am I going to get the best return, and which crop is going to be easiest to move?”

Just like the weather, predictability matters for policy, too. According to Khurana, in the last 6 to 8 months, farmers’ frustration with the government has only increased due to “multiple shifts in policies”. But he notes with cautious optimism that there are signs that “the government is listening to industry — we hope that continues.”

In particular, Khurana would like to see the government ease foreign trade policies, so that traders can easily import the food substitutions they need when the weather and other factors push supply below demand. “Open trade relationships can allow us to procure the pulses we need to fulfil demand.”

Disclaimer: The opinions or views expressed in this publication are those of the authors or quoted persons. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Global Pulse Confederation or its members.